This is the second in a three-part series examining the theological ideas of Søren Kierkegaard through the work of three contemporary church critics. The first part can be found here.

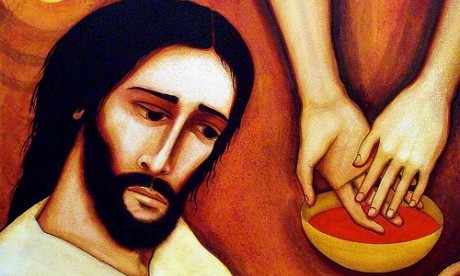

To me, the most memorable voice in the St. John’s Passion has always been that of Pontius Pilate. After struggling fruitlessly to undo the inevitability of Christ’s death, confronted with the real certainty of executing the world’s most innocent person, Pilate is shaken to the core. He is left clinging to one existential question: “What is truth?”

As we are often reminded on Good Friday, Pilate is a puppet, the local symbol of a government and a society that required Christ dead to avoid losing its own power and influence. Pilate hides his own responsibility for the death of Jesus behind the will of his people and his Caesar.

“Why is it,” Kierkegaard asks, “that people prefer to be addressed in groups rather than individually? Is it because conscience is one of life’s greatest inconveniences, a knife that cuts too deeply? We prefer to ‘be part of a group,’ and to ‘form a party,’ for if we are part of a group it means goodnight to conscience.”

Pilate’s error, Kierkegaard concludes, is a fundamental failure to recognize that Christ is the truth: more specifically, that Christ’s life is testament to the truth and that truth requires participating in that life and experience. Pilate’s greatest barrier to unambiguous participation in the truth was the comfort and security of a powerful institution. By Kierkegaard’s time, the powerful institution was the Danish church.

The “grand cast of characters” that make up the clergy, along with their “complete inventory” of buildings and sacred objects work well, Kierkegaard argues, only when an authentic Christianity is present in the hearts of believers. If the faith of the people is weaker, however, these objects merely create the false impression of faithfulness: “The illusion of a Christian nation, a Christian ‘people,’ masses of Christians, is no doubt due to the power that numbers exercise over the imagination.” Continue reading

Sources

- Chase Nordengren in National Catholic Reporter

- Image: Clarion Journal