San Salvador. In the bright morning sunlight of March 24 1980, a car stopped outside the Church of the Divine Providence.

A lone gunman stepped out, unhurried.

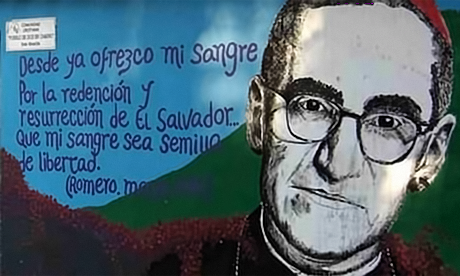

Resting his rifle on the car door, he aimed carefully down the long aisle to where El Salvador’s archbishop, Oscar Arnulfo Romero, was saying mass.

A single shot rang out.

Romero staggered and fell. The blood pumped from his heart, soaking the little white disks of scattered host.

Romero’s murder was to become one of the most notorious unsolved crimes of the cold war.

The motive was clear. He was the most outspoken voice against the death squad slaughter gathering steam in the US backyard.

The ranks of El Salvador’s leftwing rebels were being swelled by priests who preached that the poor should seek justice in this world, not wait for the next.

Romero was the “voice of those without voice”, telling soldiers not to kill.

The US vowed to make punishment of the archbishop’s killers a priority. It could hardly do otherwise as President Reagan launched the largest US war effort since Vietnam to defeat the rebels. He needed support in Washington, which meant showing that crimes like shooting archbishops and nuns would not be tolerated.

The ordering of the murder was blamed on the bogeyman of the story, a military intelligence officer called Major Roberto D’Aubuisson who had, conveniently for Washington, recently left the army.

In the weeks before the murder, he was repeatedly on television using military intelligence files to denounce “guerrillas”. Those he accused were often murdered. Romero was near the top of the list.

But US promises to bring justice came to nothing.

With no trigger-man, gun or witnesses, officials claimed lack of evidence.

D’Aubuisson went on to become one of El Salvador’s most successful politicians before throat cancer killed him at the end of the civil war 12 years later – the revenge of God, many concluded.

However, new evidence suggests that Washington not only knew far more about the killing than it admitted – but also did nothing to investigate for fear of jeopardising its war effort.

Vital evidence was ignored.

Key witnesses, including the most likely gunman, were killed by those supposed to be investigating.

Seven years and 50,000 deaths after Romero’s murder, I was feeling out of my depth as a novice reporter sitting on a park bench talking to a young deserter from Major D’Aubuisson’s death squads who called himself Jorge. Continue reading

Image: Salt and Light TV