The little-known story of the murder of 33 Trappist monks by Chinese Communists in 1947:

“The body of Christ which is the Church, like the human body, was first young, but at the end of the world it will have an appearance of decline.” — St. Augustine

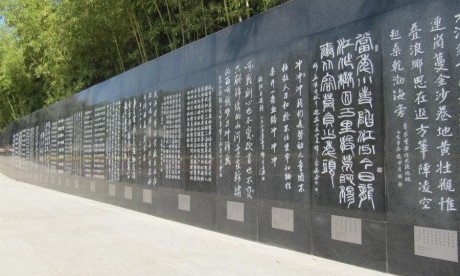

As I sat with Brother Marcel Zhang, OCSO (b. 1924), in his Beijing apartment, I thumbed through his private photographs of Yangjiaping Trappist Abbey. Some were taken before its destruction in 1947, and some he had taken during a recent visit to the ruins. What was once a majestic abbey church filled with divine prayer and worship had been reduced to debris and an occasional partial outline of a gothic window. When the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) attacked the monastery in 1947 and began its cruel torments against the monks, Zhang was one of the monks. He shared with me some of his recollections, no doubt at great risk. As we looked at a picture of the Abbey church as it appears today, where the monks gathered for daily Mass prior to 1947, Zhang paused to contemplate the ruins. “It’s already gone . . . already, the church is like this,” he said, insinuating that the ruins of the Abbey “church” metaphorically represented the “Church” in China, still haunted by the past, still tormented in the present.1

After the People’s Court had demanded the collective execution of the monks of Our Lady of Consolation Abbey at Yangjiaping, the Trappists were bound in heavy chains or thin wire, which cut deeply into their wrists, and were confined to await their punishments. Brother Zhang recalled that during the many trials, Party officials presiding over the interrogations accused the Trappists of being, “wealthy landlords, rich peasants who exploit poor peasants, counterrevolutionaries, bad eggs, and rightists”. Essentially, they were charged with all of the “crimes” commonly ascribed to the worst classes in the Communist list of “bad elements.”2 Normally, only one of these accusations was sufficient to warrant an immediate public execution, but some of the accused from the abbey were foreigners, and news that Nationalist forces were on their way to save the monks alarmed the Communist officers. Punishments had to be inflicted on the road, on what became the Via Crucis of the Trappist sons of Saint Benedict. More interrogations were staged during stops, and Brother Zhang noted that new trials, or “struggle sessions” (鬥爭) as he called them, were orchestrated at every village. Zhang himself was questioned more than twenty times at impromptu People’s Courts. He remembered that he was treated with much more leniency than the priests, as he was still only a young seminarian in 1947. The priests were much more despised. “After the interrogations,” Zhang recalled, “we would go out to relieve ourselves, and I saw the buttocks of the priests, which were red [from their beatings]; the flesh hung off like meat.”3 Chinese Catholics who know about the Yangjiaping incident refer to these torments as a “siwang xingjun,” 死亡行軍 or a “death march,” and this is when most of the Trappists who died received their “palms of martyrdom.” Continue reading

Sources