When I was young the intellectual milieu was shaped by the need to come to terms with the unprecedented crimes and the general moral collapse that had taken place on European soil following the outbreak of great power conflict in August 1914 – Hitler and Stalin, the Holocaust and the Gulag, the concentration camps and genocide, the tens of millions of deaths that had occurred in two unprecedentedly barbarous wars.

For me the most important book on the contemporary crisis of civilization was Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, a complex study of racism, imperialism, anti-semitism and the regimes that had emerged in Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union.

The book was important to me not only because of its formal arguments and its insights but because it was written in a tone that seemed, unlike any other work I had read, to have risen to the extremity of the crimes and the breakdown it was struggling to understand and to explain.

In our own age we are faced with a crisis of civilisation of equivalent depth but of an altogether different kind – the gradual but apparently inexorable human-caused destruction of the condition of the Earth in which human life has flourished over the past several thousand years, at whose centre is the phenomenon we call either global warming or climate change.

During the past decade I have read scores of books and thousands of articles, many outstanding, examining from every conceivable angle and also trying to explain the wreckage we are knowingly inflicting on the Earth.

It was however not until last week that I read a work whose tone and scope seemed to me, like Arendt’s Origins, fully adequate to its theme.

Al Gore and the Pope

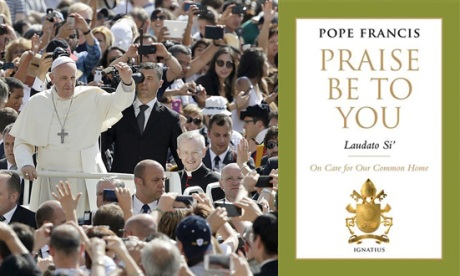

That work was Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home – in my opinion one of the most important documents of our era.

There can be little doubt that the papal encyclical is the most consequential intervention in the discussion of climate change since Al Gore’s film An Inconvenient Truth.

But as an intervention it is of an interestingly different and more radical kind.

The implication of Al Gore was that the crisis we were facing had arisen as a consequence of an unhappy but nevertheless innocent accident.

The condition of the Earth was under threat because the unprecedented material prosperity of industrial civilisation had been based on the disastrous but unanticipated and unanticipatable consequence of its source of energy – the burning of fossil fuels.

Knowing now what we do, all that was required to overcome the crisis, Gore argued, was to replace fossil fuels with renewables – solar, wind, hydro, geo-thermal.

No doubt that transition would be anything but easy and to succeed would require great reserves of political skill and will.

For Al Gore the climate crisis was however a mere hiccup in the course of history.

Following the transition from fossil fuels to renewables, the fundamental human story – of expanding material prosperity through endless economic growth – would be able to be resumed with its bounty, universalised through the generosity of the developed world, spreading gradually to every corner of the Earth.

For Al Gore humankind did face a crisis of the most serious kind.

But for him nevertheless, the myth of unending material progress, a core American or indeed Western faith, was untouched.

The papal encyclical is different

Like Al Gore, indeed like all rational people, Pope Francis accepts the consensual conclusions of the climate scientists: that through the burning of fossil fuels human action is causing the Earth to warm dangerously; that this warming has already inflicted great harm and is certain to inflict catastrophe in the future, especially on poorer peoples and on future generations; that it will poison the oceans, transform lands into desert, and lead to a tragic loss of bio-diversity; and that if the effects of global warming are to be mitigated there is no alternative to the speedy elimination of fossil fuels and the embrace of renewable sources of energy.

According to the Pope, “this century may well witness extraordinary climate change and unprecedented destruction of eco-systems’.’

Indeed, because of its failure to abandon fossil fuels ”the post-industrial world may well be remembered as the most irresponsible in human history.”

All this is deftly summarised in the encyclical.

There is nothing about this account that is unusual or with which Al Gore would in any way disagree.

Where Al Gore and Pope Francis part company is over the relation of the climate crisis to contemporary industrial civilisation.

For Gore the fundaments of this civilisation are unquestioned.

For Pope Francis the climate crisis is only the most extreme expression of a destructive tendency that has become increasingly dominant through the course of industrialisation.

Judaeo-Christian thought “demythologised” nature, breaking with an earlier worldview that regarded nature as “divine”.

But as the industrial age advanced, by ceasing to regard the Earth, our common home, with the proper “awe and wonder”, humans have come to behave as “masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits to our immediate needs.”

“Never have we so hurt and mistreated our common home as we have in the past two hundred years.”

The vision of the encyclical is not straightforwardly anti-modernist, although I have no doubt that it will be mischaracterised in this way.

The advances in the fields of medicine, engineering and communications are welcomed.

“Who,” Francis exclaims at one point in the encyclical, “can deny the beauty of an aircraft or a skyscraper?”

But for him, in the end, the treatment of the Earth as a resource to be mastered and exploited; the limitless appetite for consumption that has accelerated during the past 200 years of the industrial age and has culminated in our “throwaway culture”; and the most extreme consequence of the contemporary crisis of post-industrial society, the climate emergency – are inseparable phenomena, part of a general and profound civilisational malaise.

“Doomsday predictions,” the encyclical claims, “can no longer be met with irony or disdain. We may well be leaving to coming generations debris, desolation and filth. The pace of consumption, waste and environmental change has so stretched the planet’s capacity that our contemporary lifestyle, unsustainable as it is, can only precipitate catastrophe.”

Why has this come to pass? Continue reading

– Robert Manne is Emeritus Professor and Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow at La Trobe University and has twice been voted Australia’s leading public intellectual.