Whenever Pope Francis visits prisons, during his whirlwind trips to the world’s peripheries or at a nearby jailhouse in Rome, he always tells inmates that he, too, could have ended up behind bars: “Why you and not me?” he asks.

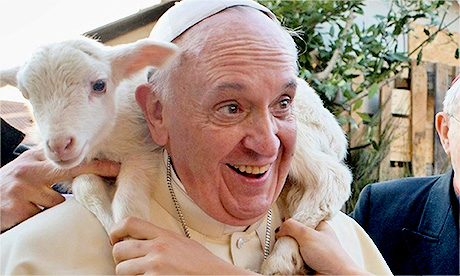

That humble empathy and the ease with which he walks in others’ shoes have won Francis admirers around the globe and confirmed his place as a consummate champion of the poor and disenfranchised.

But as he marks the fifth anniversary of his election Tuesday and looks ahead to an already troubled 2018, Francis faces criticism for both the merciful causes he has embraced and the ones he has neglected.

With women and sex abuse topping the latter list, a consensus view is forming that history’s first Latin American pope is perhaps a victim of unrealistic expectations and his own culture.

Nevertheless, Francis’ first five years have been a dizzying introduction to a new kind of pope, one who prizes straight talk over theology and mercy over morals — all for the sake of making the Church a more welcoming place for those who have felt excluded.

“I think he’s fantastic, very human, very simple,” Marina Borges Martinez, a 77-year-old retiree, said as she headed into evening Mass at a church in Sao Paulo, Brazil. “I think he’s managed to bring more people into the church with the way he is.”

Many point to his now famous “Who am I to judge?” comment about a gay priest as the turning point that disaffected Catholics had longed for and were unsure they would ever see.

Others hold out Francis’ cautious opening to allowing Catholics who remarry outside the church to receive Communion as his single most revolutionary step. It was contained in a footnote to his 2016 document “The Joy of Love.”

“I have met people who told me they returned to the Catholic faith because of this pope,” Ugandan Archbishop John Baptist Odama, who heads the local conference of Catholic bishops, said.

“Simple as he may be, he has passed a very powerful message about our God who loves everybody and who wants the salvation of everyone.”

Another area in which Francis has sought change extends into global politics, with his demand for governments and individuals to treat migrants as brothers and sisters in need, not as threats to society’s well-being and security.

After a visit to a refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece, Francis brought a dozen Syrian Muslim refugees home with him on the papal plane.

The Vatican has turned over three apartments to refugee families. Two African migrants recently joined the Vatican athletics team.

His call has gone largely unanswered in much of Europe and the United States, though, where opposing immigration has become a tool in political campaigns.

Italians in the pope’s backyard voted overwhelmingly this month for parties that have promised to crack down on migration, including with forced expulsions. Continue reading

- Image: Xavier School