As the U.S. Catholic bishops gather in Baltimore to discuss controversial issues such as clerical sexual abuse and racism, some people are talking about the threat of schism.

History shows that the possibility of schism is always present, but the odds against schism today are high.

First, in order to have a schism, you need at least one bishop interested in breaking away.

If a priest and his parishioners decide to split from the church, that is not a schism. If a priest leads a breakaway, it usually fades when the priest dies.

Schismatic bishops can ordain other bishops and priests, so the breakaway has a better chance of continuing; the Great Schism of 1054 between Eastern and Western Christianity has lasted almost 1,000 years.

On the other hand, the most famous schism of the 20th century was led by French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre against many of the reforms mandated by the Second Vatican Council, including ecumenism, religious freedom and putting the liturgy into the vernacular.

In 1988 he ordained four bishops without the approval of the pope, but he took only a relatively small number of Catholics with him into schism.

After his death, his group has not grown significantly and has experienced its own splits. (Benedict XVI also made the group less attractive by permitting greater use of the pre-Vatican II Latin Mass.)

There are certainly bishops who do not like the way Pope Francis is leading the church. Archbishop Carlo Viganò has called for the pope to resign.

Others, including Cardinal Raymond Burke, have criticized Pope Francis, but so far none of them has indicated any interest in going rogue.

They look upon him as an aberration that will be corrected by the next papacy. After all, at 81 years of age, he is older than many of his critics. They can wait him out.

In order to have a schism, too, you need truly divisive issues that split the community, not just the bishops.

Conservative bishops have complained that Pope Francis is too permissive on allowing divorced and remarried Catholics to go to Communion, too soft on Catholics who practice birth control and too welcoming to LGBT Catholics.

Yet public opinion polls show that Catholics, even those who go to church weekly, are much more liberal than the pope on these issues.

While conservative bloggers and commentators may rant about these issues, the faithful are not going to follow a bishop into schism because they want the rules on birth control, divorce and homosexuality strictly enforced.

Feelings are stronger on abortion, but Pope Francis has repeatedly expressed his opposition to abortion, although early in his reign he indicated he was not going to “obsess” over it since everyone knows the church’s position.

The topics under discussion at the Baltimore meeting, sex abuse and racism, are certainly controversial, but the bishops are united in their opposition to racism and united in panic in dealing with the sexual abuse crisis.

On sex abuse, the major split is not among the bishops, but between the bishops and their people.

Schism: Politics rather than theology

History’s most important schisms have been more about politics than theology.

That was true of the Great Schism and the Anglican split under Henry VIII. Today the schism between Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox believers is all about politics.

Similarly, some also considered the bishops belonging to the Chinese Patriotic Association to be in schism because they also ordained bishops without Vatican approval.

The Vatican avoided calling them schismatic, and a major goal of Pope Francis’ recent agreement with the Chinese government was to mend the divide among Chinese Catholics, even if it meant accepting some bishops the Vatican would never have willingly ordained.

The U.S. Catholic Church has been extraordinarily successful in keeping political opponents in the fold.

While many Protestant churches split during the Civil War, the Catholic Church stayed united. In the recent midterm elections, Catholics evenly split their vote between Republican and Democratic candidates, as they did in the last presidential election, while other denominations tended to go overwhelmingly for one party.

Shaken not stirred

This unity is feeling some strain but still appears strong.

According to the Pew Research Center, 84 percent of Catholics have a favorable opinion of Pope Francis, but when that is broken down by party, the numbers are 89 percent for Democratic Catholics and 79 percent for Republican Catholics.

The latter is still an extraordinarily high number; any politician would love that rating. But it shows how partisanship can weaken unity.

Pew also found that 55 percent of Republican Catholics think Pope Francis is too liberal.

The pope’s talk of building bridges rather than walls and his strong support of refugees and migrants go counter to Trump orthodoxy.

But these Republicans don’t appear ready to abandon the church.

Nor do the American bishops appear ready to abandon the sensitivities of either side.

While some would prefer to focus on abortion, gay marriage and religious liberty, none of them has supported the anti-immigrant policies of the Trump administration.

This year alone, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has issued 21 press releases dealing with immigration, all critical of the Trump administration.

True, they want pro-life judges appointed to the Supreme Court, but unlike evangelical leaders, the Catholic bishops have not sold their souls to the Republican Party.

They still follow Catholic social teaching with its concern for workers, the poor and the marginalized. In truth, they are uncomfortable with both parties.

The issue in Baltimore is not schism but credibility.

If the bishops are not capable of credibly dealing with sex abuse during their meeting in Baltimore, the faithful will not break away; they will simply leave.

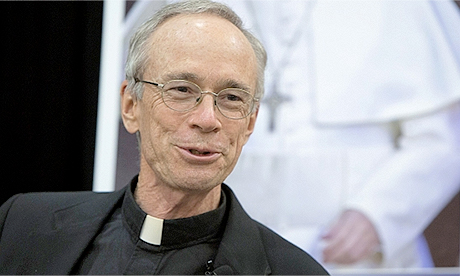

- Thomas J. Reese SJ, is a Senior Analyst at RNS. Previously he was a columnist at the National Catholic Reporter (2015-17) and an associate editor (1978-85) and editor in chief (1998-2005) at America magazine. First Publlished in RNS. Republished with permission.

- Image: DomRadio.de

- Image: St Louis Post Dispatch