What took place next inside the Sistine Chapel was hidden from the outside world.

Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re first explained the voting process and then asked the cardinals if they were ready to vote.

They were! Everyone was anxious to do so, as this would reveal where the Holy Spirit was leading them.

The first phase of the process began with the distribution of ballot sheets to the electors.

Before the voting started, and in accordance with the apostolic constitution “Universi Dominici Gregis,” the most junior cardinal elector then extracted at random the names of three “scrutineers,” three “infirmarii” and three “revisers” to supervise the first voting session.

The second phase was the secret ballot.

Each cardinal had before him a ballot form, rectangular in shape, on which were printed in Latin the words “Eligo in Summum Pontificem” (“I elect as Supreme Pontiff”), and underneath there was a space for the name of the person to whom he wished to give his vote.

The electors were expected to write in such a way that they could not be easily recognized by their handwriting.

Once the cardinal completed his ballot form, he had to fold it lengthwise, so that the name of the person he voted for could not be seen.

Once all the electors had written the name of their chosen candidate and folded the ballot sheets, then each cardinal took his ballot sheet between the thumb and index finger and, holding the ballot aloft so that it could be seen, carried it to the altar at which the scrutineers stood and where there was an urn, made of silver and gilded bronze by the Italian sculptor Cecco Bonanotte, with an image of the Good Shepherd on it.

The urn was covered by a similarly gilded plate to receive the ballot sheets.

On arrival at the altar, the cardinal elector stood under the awesome painting of Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” and pronounced the following oath in a clear and audible voice: “I call as my witness Christ the Lord, who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one who, before God, I think should be elected.”

He then placed his ballot sheet on the plate and tilted the plate in such a way that the sheet fell into the urn.

Finally, he bowed in reverence to the cross and returned to his seat, and the next elector then walked to the altar.

No Smartphones

The conclave organizers took high-security measures to prevent the possibility of transmission by smartphone from inside and electronic interception by outside agencies or individuals.

After all 115 electors had cast their votes, the three scrutineers came forward to count them.

It was a moment of high tension.

Everybody watched the ritual with rapt attention.

The first scrutineer shook up the ballot sheets in the urn, which was first used at the last conclave, to mix them.

Then another scrutineer began to count them, taking each ballot form separately from the first urn and transferring it to a second urn, exactly like the first, that was empty.

The constitution decrees that if that the number of ballot sheets cast does not correspond exactly to the number of electors present then that round of balloting is declared null and void.

When the number of ballot sheets corresponds exactly to the number of electors, the process continues with the opening of the ballots.

The three scrutineers sit at the table in front of the altar.

The first opens the ballot sheet, reads the name silently, and passes it to the second scrutineer.

The second does likewise, and then passes it to the third, who reads the name written on the sheet and then, in a loud voice, announces it to the whole assembly and next records it on a paper prepared for this purpose.

The windows of the Sistine Chapel had been blacked out.

But that was considered totally inadequate given the advanced state of modern communications technology and the risk of electronic interception so, as in 2005, the conclave organizers took high-security measures to prevent the possibility of transmission by smartphone from inside and electronic interception by outside agencies or individuals.

They installed state-of-the-art jamming systems, including a Faraday cage.

The floor of the chapel had been raised about one meter and covered with wooden boards for installation of the system.

This time, however, the organizers went even further than at the last conclave to prevent the possibility of interception; they took the extraordinary decision not to use the sound-amplification system inside the Sistine Chapel.

The reason for this, it seems, goes back to the 2005 conclave, when the Swiss Guard standing on duty outside the doors of the chapel could sometimes hear what was being said inside, especially when the vote counts were announced over the P.A. system.

Consequently, before the first vote, Cardinal Re asked Cardinal Juan Sandoval Íñiguez, the 79-year-old emeritus archbishop of Guadalajara, who was known to have a powerful voice, to stand in the middle of the chapel and proclaim in a loud voice the names read out by the third scrutineer.

As the third scrutineer read out a name on a ballot sheet, Cardinal Sandoval repeated it so that all could hear.

There was an air of high suspense inside the Sistine Chapel as the results were being announced.

For the first time the electors were revealing their choices; they were putting their cards on the table.

After reading out the name on each individual ballot, the third scrutineer pierced the sheet through the word “Eligo” with a needle and thread; this was done to combine and preserve the ballots. When the names on all the ballots had been read out, a knot was fastened at each end of the thread and the joined ballots were set aside.

This was followed by the third and last phase of the voting process, which began with adding up the votes each individual had received. The results held several big surprises.

Before the conclave, several cardinals had predicted that there would be a wide spread on the first ballot, but few had imagined how wide: 23 prelates received at least one vote.

Before the conclave, several cardinals had predicted that there would be a wide spread on the first ballot, but few had imagined how wide: 23 prelates received at least one vote on the first ballot; this meant that one out of every five cardinals present got at least one vote, with four cardinals getting 10 or more votes.

The top five vote-getters in the first round were as follows:

- Scola 30

- Bergoglio 26

- Ouellet 22

- O’Malley 10

- Scherer 4

Angelo Scola came first with 30 votes, but he did not receive as many votes as had been predicted by some cardinals and the Italian media.

The big surprise was Jorge Bergoglio, who came in at second place, close behind Scola, with 26 votes.

His total, in fact, would have been 27 if an elector had not misspelled his name, writing “Broglio” instead of Bergoglio on the ballot sheet. It was a most promising start for the archbishop of Buenos Aires. Continue reading

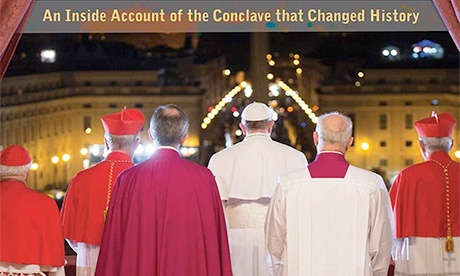

- The above are excerpts drawn from The Election of Pope Francis: An Inside Account of the Conclave That Changed History (Orbis Books, 2019), by Gerard O’Connell, America’s Vatican correspondent.