In the lead-up to the 2020 election, Democratic candidates and party officials have worked hard to counter the narrative that their party has a “religion problem.”

They’ve hired faith outreach directors, met with religious activists and courted the votes of people of a wide range of faith groups throughout the Democratic primary season.

But experts say the party still has failed to win over the largest religious demographic in the country: white Christians.

Much has been written about President Donald Trump’s support among white evangelicals in the 2016 election when he won 80% to 81% of the group.

But less attention has been paid to how Trump also swept all major categories of white Christians.

He won 60% of white Catholics on Election Day, according to a Pew analysis of exit polls, and a January 2017 Public Religion Research Institute survey found 57% of white mainliners had a favourable view of the president around the time of his inauguration.

Trump’s success with white Christians outpaces most other Republican presidential candidates in recent memory.

It also reflected a larger shift in party affiliation along religious lines. According to Pew, 48% of white Christians identified as Republicans or leaned toward the party in 2007. By 2014, that number jumped to 56%.

The change signals a steady increase of broad-based white Christian support for the Republican Party and its candidates, a phenomenon political scientists credit to a complex mix of religion, identity and race.

While Democrats have been able to eke out victories in previous elections by relying on ever-winnowing slivers of the religious vote, the exodus of white Christians from their ranks may be harder to ignore this year.

“Almost every major majority-white Protestant denomination in America is majority-Republican now, and almost all of them have become more Republican over the last 10 years,” Ryan Burge, political science professor at Eastern Illinois University, told Religion News Service in an interview.

The trend may surprise some mainline Protestants, whose leadership often skews liberal.

But according to the Cooperative Congressional Election Study, Republicans are the most popular political affiliation among members of the United Methodist Church (53.7%), the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (49.3%) and the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) (49.9%).

Burge said this rightward shift has increased over time.

Citing CCES data, he said that over the last 10 years the United Methodist Church became 5% more Republican, the Episcopal Church 4.7%, the ELCA 3.5% and the United Church of Christ 4%.

Scholars say there are multiple factors influencing the shift.

Many point to the rise of the religious right, which spent decades pushing conservative religious voters to focus on opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion.

According to a 2018 survey from PRRI, majorities of white evangelical Protestants (65%) believe that abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, as do sizable percentages of white mainliners (35%) and white Catholics (42%).

Penny Edgell, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota, said the growth of the so-called nones — Americans who claim no religious affiliation — also plays a role.

That group, which generally espouses deeply liberal views regarding same-sex marriage and abortion, includes a significant number of younger voters who have broken ties with evangelicalism and mainline Christianity, she said.

“The liberal/moderate Protestant ranks have declined as people who were ‘moderately’ religious have left altogether as religion has become more politicized and associated with the political right,” Edgell told RNS in an email.

Clemson sociologist Andrew Whitehead pointed to the influence of Christian nationalism, an ideology that champions the belief that the United States should be a Christian nation.

Whitehead argues that “cultural framework” has long been trumpeted by leaders of the religious right and was embraced during the 2016 election by Trump, who often declares at his rallies, “We don’t worship government, we worship God.”

Whitehead also says that race plays a role in the white Christian embrace of the Republican Party.

“The Republican Party repeatedly is able to tell the narrative of a Christian nation, a chosen exceptional nation, and there is a racial aspect to that,” said Whitehead, who recently co-authored the book “Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States.”

He added that conservative Christian educational institutions such as Liberty University, whose president endorsed Trump and where the commander in chief has spoken twice during his ascending to the presidency, were founded as “segregation schools.”

Christian nationalist rhetoric can “cover over racialized language with religious symbolism so you don’t even see the race part,” he said.

Burge agrees. He also insisted that race is a better predictor of voting patterns than theological outlook.

“Race matters more than religion right now,” he said.

“White Christians are white, and the Republican Party has become the party of whites, and the Democratic Party has become the party of nonwhites.”

Despite the potency of these forces, scholars say there may be ways for progressives to chip away at the GOP’s gains among white Christians. Whitehead suggested Democrats could appeal to what he called “accommodators” — voters who are Christian and who believe religion in general can be a force for good.

“I think there’s room to make a case to them that Christianity, maybe alongside other religions, can help create a better America or can help solve some of these public social issues,” he said.

“Fixing” social issues may be a hard sell for some voters, however.

Ruth Braunstein, professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut, noted that the percentage of Americans who believed that America’s best days are behind it increased from 2012 to 2015 — 38% to 49%, respectively, according to PRRI.

That belief was especially prevalent in 2015 among white evangelical Protestants (60%) and white mainline Protestants (55%).

The cynicism of white Protestants contrasts sharply with unaffiliated Americans, a majority of whom (58%) believed America’s best days are ahead.

Although the group tends to vote in lower percentages than white evangelical Christians, Braunstein suggested Democrats may have more luck mobilizing the energy of unaffiliated voters than retrieving white Christian support.

“It does raise the question of whether Democrats need to appeal broadly to (white Christian) voters, or whether they should be trying to figure out how to appeal more broadly to religiously disaffiliated voters who are more likely to be young and whose views on a lot of these issues are significantly different than older voters,” she said.

However, courting diverse liberal voters can be a complicated venture.

Braunstein cited research in which she pinpointed at least two different dominant political narratives among liberals during the 2016 election: a “traditional liberal, multicultural progress narrative” perpetuated by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and a “revolutionary change narrative” embraced by Sen. Bernie Sanders.

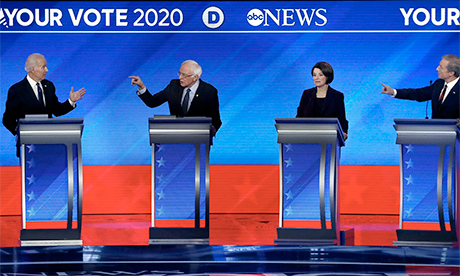

Both narratives have reemerged and divided the party throughout the 2020 Democratic primary season.

While religious voters resonate with both, they may sit in slightly different camps. For example, Edgell suggested that the remaining liberal-leaning white Christians — such as those who rushed to support Sen. Amy Klobuchar in the recent New Hampshire primary — may be attracted to a message that is more about revision than revolution.

“The remaining white liberal/moderate Protestants may be more suburban swing-voter types than march-for-racial-justice types,” Edgell said.

Braunstein noted that while some white Christians believe that the country’s best days are ahead of it, the idea was most popular with black Protestants, Catholics and those of no faith. To unite their support Democrats could turn to the rhetoric of an ascendant religious left — chief among them activist and Poor People’s Campaign co-chair the Rev. William Barber — but only if invoked with caution.

“That is a tightrope that Democratic leaders have to walk in a way that Republican leaders don’t,” she said.

- Jack Jenkins is an award-winning journalist and national reporter for the Religion News Service. Republished with permission.