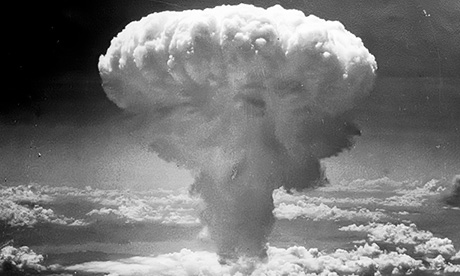

The closer we look at decisions to deploy a second atomic weapon against Japan on August 9, 76 years ago, the more morally audacious the tactic appears.

Step outside the American explanatory cloud—we bombed military installations to force unconditional imperial surrender—defining public understanding to see: the US Government explicitly targeted civilian populations, a violation of international law and codes of military conduct.

Diplomats and archivists at the Vatican are convinced the attack against Nagasaki was a strike against Japan and the Catholic Church.

They provide a rationale rarely discussed, in the face of general puzzlement over unexplained aspects of the tragedy.

Ground Zero: A Catholic Spiritual Center

The second atomic attack was a near-direct hit on Asia’s largest cathedral, in the country’s renowned Catholic settlement, Urakami, a residential district of Nagasaki—significantly north of the city’s commercial centre and Mitsubishi’s shipyard.

The ties between Nagasaki and the Catholic Church go way back:

- A lord donated land to Jesuit missionaries from Portugal in 1580.

- The new religion spread so quickly it was outlawed as a threat to local rulers.

- Twenty-six martyrs were crucified in the city’s hills in 1597.

- The only port continuously open to foreign trade, it was a stronghold of secret faith during the long suppression of Christianity (1614-1873).

“Big Boy,” the plutonium implosion bomb detonated over Urakami, killed about 40,000 people immediately and another 30-40,000 by the end of the year.

It decimated 85 per cent of the Catholic community, many descendants of the “Hidden Christians” (Kakure Kirishitans), who concealed the faith behind Shinto and Buddhist practice.

It was impossible for military planners not to know the area’s history and Catholic significance.

So famous was this region as a spiritual centre the charismatic German Franciscan, St Maximum Kolbe, opened a monastery there in 1930. (Eleven years later he was murdered in a concentration camp.)

The U.S. required visual bombing, not radar reliance.

In the late morning on August 9, bombardier Kermit Beahan recalled seeing clouds open, and “the target was there, pretty as a picture.”

What does the mission’s target map look like? We can’t know…it’s missing from the National Archives.

Hidden Hand Adds “Nagasaki”

President Harry Truman learned about the atomic weapons program when he took office.

By then, operational momentum for testing both “gadgets,” a uranium bomb and plutonium implosion device, saturated decision-making.

A “target committee” appointed by the military, comprised of officers and nuclear scientists, zeroed in on the least humane option: detonating the bombs to maximize damage to entire cities of at least three miles diameter.

Yet, experienced war hands such as Dwight David Eisenhower, General of the Army, and General Omar Bradley, opposed their use. Eisenhower explained later, “Japan was already defeated and…dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary.”

Declassified documents portray Stimson as ambivalent: He decried civilian casualties of incendiary bombings, telling Truman on June 6 he didn’t want the US “to get the reputation of outdoing Hitler in atrocities.”

While in Potsdam, he went directly to the president to request protection for the ancient city of Kyoto based on cultural value. Stimson reported in his diary, the president concurred.

Nagasaki did not show up on hit lists generated in May and June.

Its mountainous, irregular terrain failed target committee preferences. Instead, the city was subjected to five rounds of brutal incendiary attacks.

Top-tier A-bomb targets escaped firebombing so the catastrophic blast would get full credit for destruction. Allied POW camps in Nagasaki argued against obliterating it, too.

At the very last minute, Nagasaki appears as a potential target on a draft strike order dated July 24—as a handwritten add-on, coinciding with the July 24 Stimson-Truman meeting on targets.

A typed, Top Secret document commands that the US “will deliver its first special bomb” to “Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata in the priority listed.”

In pen, someone struck “and” as well as “in the priority listed,” inserting with an arrow “and Nagasaki” after “Niigata.”

The amended strike, order with Nagasaki added, was officially circulated the next day.

According to historian Alex Wellerstein who first highlighted the document, the hand that added Nagasaki is unidentified.

Series of Unfortunate Events

Persistent American accounts of the second bombing mission posit a series of unfortunate events:

- The B-29 carrying Big Boy had fuel pump problems.

- It wasted inflight time waiting for a camera plane that never showed.

- Three times, it tried to target Kokura but couldn’t eyeball the hit.

- Then, its next target, Nagasaki, was concealed by cloud cover.

Japanese commentators have various theories but few think the US annihilated Urakami by mistake.

Some believe the historic site was destroyed because the cathedral was used to store rice and other food supplies for the imperial army.

An immediate scapegoating reflex emerged among non-Catholic Nagasaki survivors who blamed the blasphemous worship of a foreign god for bringing ruin to their city.

Several recent studies explore how Urakami’s Catholic hibakusha (atom bomb survivors) deployed the theology of martyrdom and forgiveness to make sense of the incomprehensible.

Gwyn McClelland in Dangerous Memory in Nagasaki: Prayers, Protests, and Catholic Survivor Narratives and Chad Diehl in Resurrecting Nagasaki both point to the key role played by Dr. Takashi Nagai, a Catholic lay leader, hibakusha, and author of The Bells of Nagasaki.

In a eulogy for the dead in front of the cathedral’s ruins, Nagai called the bombing an act of providence: the sacrifice of innocent blood atoned for the sins of a world at war.

This framing reassured Christian victims, but it had a silencing impact—reinforcing the self-suppression they practiced for 250 years. US command helped make “the saint of Urakami” a bestselling author: Nagai was the only hibakusha allowed to publish internationally.

For decades, occupation forces appropriated Nagai’s explanation, as did the Japanese—Emperor Hirohito visited Nagai personally—because it absolved both of responsibility.

What Rome Believes

The Vatican has never publicly discussed the bias it sees behind US willingness to stab Japan’s Catholic heart on Aug 9, 1945, but privately, archivists and experts in Rome remind me of an intense diplomatic row between Washington and Rome over Japan that marred relations throughout the war.

Three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Pope Pius XII established diplomatic ties with the imperial power in Tokyo.

When the Church informed allied officials, they howled. Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles called the pope’s decision “deplorable.”

President Franklin Roosevelt found it “unbelievable.”

Pius’ response to Washington, according to a US envoy living in the Vatican was self-evident: diplomatic relations don’t mean approving all actions of a foreign interlocutor.

Interstate diplomacy is an essential way the Catholic Church protects its believers and advances its mission.

When the emperor’s envoys approached Rome in 1942 with a proposal Rome had long sought, the Church, pragmatically, agreed.

In its view, the Church had no choice but to engage because the empire’s advancing military was bringing more Catholics under Japanese control.

Protecting the spiritual interests of some 20 million Catholics in Japanese-occupied territory was a fundamental responsibility. Continue reading

- Victor Gaetan is senior international correspondent for the National Catholic Register and a contributor to Foreign Affairs magazine.

- Published by 19FortyFive