The Government has recently released proposals for legislating a new offence against communications that “intentionally incite/stir up, maintain or normalise hatred”.

The proposals themselves seemed to have stirred up strong reactions among people, including among some Christian churches and societies.

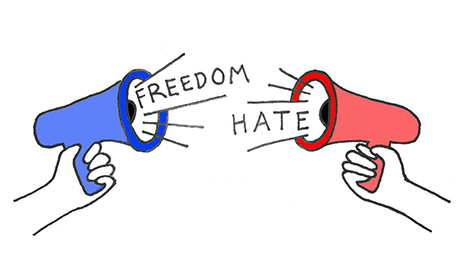

Depending on what YouTube’s algorithm has decreed you should enjoy watching, some of these reactions might be stirred by videos of so-called free-speech advocates rejecting “hate speech laws” as infringements upon the sanctity of the “free marketplace of ideas”.

By criminalising communication based on the emotions it intends to bring about, it is alleged that the Government’s proposals would stifle people’s ability to freely exchange and communicate ideas.

In support of this stance, the quote (misattributed to the philosopher Voltaire) will often be heard: “I may hate what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

This line, however, seems to overlook another serious challenge to the operation of the free speech “marketplace”: hatred itself.

Hatred posits that individuals, or the groups to which they belong, are enemies or threats which should be opposed.

The effect is a definitive conversation-stopper. “I hate who those people are, but I will defend to the death their right to say whatever they want,” said no one ever.

For Christians, there is an additional dimension to this issue.

As the opposite of Christian love or charity, hatred towards others not only causes problems for interpersonal relations; according to the New Testament, the person who hates is in darkness or in a relation of hatred towards God (1 John 2:9 and 1 John 4:20).

Judging others, we are warned, entails that we should expect to be judged in the same way by God because all such judging involves projection: attending to the sawdust in another’s eye and neglecting the plank in our own (Matthew 7:2-3).

In a short essay on “Hell as Hatred”, the Christian mystic Thomas Merton imagines hell as a place wherein all the occupants are trapped in a perpetual cycle of self-projection, in which they “know others hate what they see in them: and all recognise in one another what they detest in themselves.”

The Gospel of John offers a powerful illustration of how only a speech-act of love breaks through this cycle of judgement and hatred.

In John 8:1-11, Jesus is presented with a woman caught in adultery. Instead of joining the hostile group of male accusers in condemning the woman they surround, Jesus states that “he who is without sin” should cast the first stone.

To this, the woman’s accusers leave the scene without speaking.

What begins as a confrontation, act of judgement, and threat of death towards the woman, is dissolved by Christ pointing out the hypocrisy underneath such judgement.

It also powerfully illustrates our earlier observation about the inverse relationship between hatred and “free speech”: hate-driven accusations do not initiate conversation, and so must also end in silence.

While it remains to be seen how the legislative proposals may be applied (or misapplied) within the courtrooms of this country, the Government’s proposals are in principle ones that free speech advocates — and particularly those within the Christian faith — can and should support.

- Dr Greg Marcar is a research affiliate with the Centre for Theology and Public Issues at the University of Otago.

- First published in the ODT. Republished with permission.