Writing last week in The New York Times, linguistics professor John McWhorter waxed enthusiastic about the advent of “they” as our all-purpose third-person-singular pronoun. As in, for example: “Roberta wants a haircut, and they also want some highlights.”

“Language change is a spectator sport,” McWhorter writes.

“It isn’t whether but how things will change over time, and getting to witness a major change like what’s happening to ‘they’ is a kind of privilege, a top ticket.”

Not that I have a choice, but I’m down with this particular privilege. And here’s a modest proposal: Let’s extend it to God.

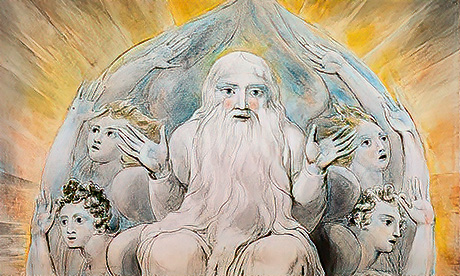

In contrast to human beings, it has long been accepted that God is not gendered, at least within the main Abrahamic theological tradition.

A phrase such as “God the Father” should be treated as a metaphor — and for those concerned about the embedded misogyny of the tradition, to say nothing of post-binary folks — a deeply problematic one.

Grammatically, if you can say ‘you are,’ you can say ‘they is.’

As a result, we have been faced liturgically as well as theologically with the imperative of gender-neutral language, which means being obliged to repeat the word “God” where a gendered pronoun would normally be used and to have recourse to the unattractive neologism “Godself” lest, God forbid, we find ourselves saying Himself.

“They,” “theirs,” “them,” and “themself” (or maybe “themselves”) solves the problem. As in: “Praise God from whom all blessings flow; / Praise Them, all creatures here below,” etc.

But, Mark, I hear some of you protesting, wouldn’t this grammatical démarche undermine monotheism, the idea of the singular God that lies at the very heart of the Abrahamic tradition?

Well, no. Monotheistic Abrahamic theology has had to deal with an embedded grammatical pluralism ever since it came into being.

That’s because the word for god in ancient Hebrew, elohim, is a plural form, used with reference to both the Hebrew god and any other god or gods — as distinct from the singular form of the Hebrew god’s actual name, JHWH (customarily translated into English as “Lord”). Here’s how that works at the start of the Book of Exodus’ 20th chapter, where God is laying down the 10 Commandments:

And elohim spoke these words, saying. I am JHWH your elohim who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. You shall have no elohim before me.

Scholars have found cognate words in other ancient Semitic languages — words in the plural form used to denote one divinity and more than one divinity. Whether it signifies an embedded polytheism in ancient Judaism is a question for the experts to debate.

The great 12th-century Jewish theologian Maimonides took a relaxed view of the matter, writing in his “Guide for the Perplexed”: “Every Hebrew knows that the term Elohim is a homonym, and denotes God, angels, judges, and the rulers of countries.” Less relaxed was the modern Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen, who called it “an almost insoluble riddle.”

So, sure, it sounds strange to refer to the biblical god with what we have been accustomed to consider plural third-person pronouns, but no doubt there were people who felt similarly when modern English jettisoned the singular “thou art” in favour of the heretofore exclusively plural “you are.”

Check out verse 10 of Psalm 86 in your Bible Hub. The King James Version translates it, “For thou art great … thou art God alone.” Just about every modern translation has, “For you are great… you alone are God.”

If you’ve not got a problem with that, you should be able to live with Exodus 15:2 as follows:

The Lord (JHWH) is my strength and my song;

they have become my salvation.

they are my God, and I will praise them,

my father’s God, and I will exalt them.

Now that would be top ticket.

- Mark Silk is Professor of Religion in Public Life at Trinity College and director of the college’s Leonard E. Greenberg Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life. He is a Contributing Editor of the Religion News Service.

- First published in RNS. Republished with permission.