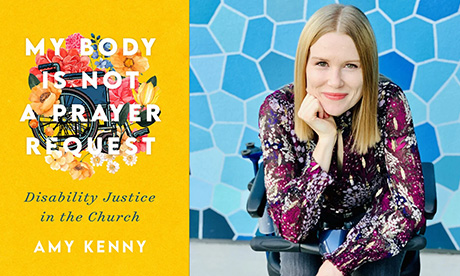

“God told me to pray for you!” is about the last thing Amy Kenny wants to hear when she cruises into church riding Diana, the mobility scooter she has named after Wonder Woman.

It’s not that she has anything against prayer.

Kenny, a Shakespeare scholar and lecturer at the University of California, Riverside who is disabled, would simply like other Christians to quit treating her body as defective.

“To suggest that I am anything less than sanctified and redeemed is to suppress the image of God in my disabled body and to limit how God is already at work through my life,” Kenny writes in her new book, “My Body Is Not a Prayer Request.”

The book invites readers to consider how ableism is baked into their everyday assumptions and imagines a world — and a church — where the needs of disabled people aren’t ignored or tolerated but are given their rightful place at the centre of conversations.

Kenny combines humour and personal anecdotes with biblical reflections to show how disabilities, far from being a failure of nature or the Divine, point to God’s vastness.

She reframes often overlooked stories about disability in Scripture, from Jacob’s limp to Jesus’ post-crucifixion scars. Abolishing ableism, she concludes, benefits disabled and non-disabled people alike.

Religion News Service spoke to Kenny about making the church what she calls a “crip space,” her belief in a disabled God and why she prefers Good Friday over Easter. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

At what point did you begin seeing your disability as a blessing?

I was told often by doctors that my spine and my leg and my body was crooked.

I began seeing how crooked and jagged creation is, the way elm trees have snaking branches and maple leaves are ragged and kangaroos don’t walk but hop.

I didn’t have any trouble thinking about those elements as beautiful and divine. Yet when applied to humans, disability was thought of as dangerous and sinful.

That just didn’t make sense to me.

So based on the idea that creation is delightfully crooked, I started to think about how my body, too, is made in the image of the Divine and its crookedness isn’t anything to be ashamed of.

Can you explain the difference between curing and healing?

I think of curing as a physical process, usually a pretty rapid one — in Western society, going to the doctor and wanting a fix for whatever illness you are experiencing.

Healing is much richer than that.

It’s deeper.

Healing is messy and complex. It takes time. It’s about restoring someone to communal wellness.

I don’t have any trouble thinking that Elm trees with snaking branches are beautiful and divine.

What is “crip space” and what does it look like in the context of a church?

Crip space is a disability community term that is reclaiming what has been used as a derogatory slur against us, cripple, as a way of gaining disability pride.

It’s saying that we are not ashamed to be disabled, that our body-minds are not embarrassments.

Crip space puts those who are most marginalized at the centre and follows their lead. So folks who are queer, black, disabled people.

Generally, churches want a checklist or a list of don’ts.

It’s much more nuanced and human than that.

It’s noticing that there’s no ramp to the building you’re in or no sensory spaces for people to take a break.

It’s noticing that the language of the songs or the sermon is ableist and changing those words.

It’s recognizing when the community is missing disabled folks.

I’ve often had that as an excuse: “We don’t have any other disabled people but you.”

Well, I wonder if that’s related to your lack of accessibility.

Could you share why you use the term body-minds?

It’s a disability community term that is attempting to undo some of that mind/body dualism. And it’s asking for us to think about how our bodies and our minds work in concert with one another.

It’s also a way of being inclusive, making sure that when we talk about disability, we’re not just talking about mobility issues. We’re not just talking about visible disabilities.

We’re also talking about hidden disabilities.

I don’t have any trouble thinking that kangaroos who don’t walk but hop are beautiful and divine.

Some churches claim they just can’t afford to make their buildings accessible. What’s your response to that?

This one cuts deep because often the people making that excuse do so in spaces that have prioritized spending money on other things.

There will be doughnuts, coffee carts, different types of sound equipment and lights. I’m not against those things, but they suggest you’re prioritizing the aesthetic over including image-bearers in your service.

It also is suggesting that church services don’t evolve.

How does Scripture talk about disabilities?

In one of my favourite passages, Jacob wrestles with God or an angel and comes away with a healing limp and a blessing.

The limp is often read as a reprimand for questioning God, but Jacob talks about it as God being gracious.

It’s one of the transformative moments that allows Jacob to witness his brother Esau as an image bearer and to begin creating a sense of interdependency, rather than hustling to prove his self-worth through lies and schemes and the accumulation of goods.

There are so many myths of ableism wrapped up in that.

We still see today people hustling to prove they are worthy of love and care.

Instead, that passage demonstrates that through disability, Jacob is able to create a sense of co-flourishing with his brother and with the community.

The New Testament shows Jesus curing people with disabilities. How should Christians read these passages traditionally interpreted to mean disability is something to be fixed?

The ninth chapter of the Gospel of John is helpful here.

It’s the story of when disciples are asking Jesus if the man who is born blind has sinned or if his parents sinned. And Jesus says neither — this is so God’s works can be revealed.

People usually make this passage about the miraculous moment, but that’s not exactly what Jesus says.

The story itself is about this larger healing that’s being offered that should restore people into a sense of communal wellness.

I wonder how our faith communities would look if we were able to understand disability as a way of revealing the living God.

You warn that, taken too far, celebrating disability can become a kind of prosperity gospel. How so?

This connects to inspiration porn — the idea, which comes from (disabled comedians and actors) Stella Young and Maysoon Zayid, that disabled people are nondisabled people’s inspiration.

It’s porn because it’s consumptive, and it turns disabled people into an object.

When we turn disabled people into inspirations, we’re reducing that person into a feel-good commercial and often assuming we don’t have to meet their access needs.

Both the prosperity gospel and inspiration porn fail to make space for the complexity of what it means to be embodied.

The prosperity gospel promises that we all get a perfect life that is successful. Inspiration porn doesn’t allow for disabled people having tough days, or being frustrated at the ableism that we’re facing.

You say you prefer Good Friday over Easter. Why is the day meaningful to you?

I relate to that Jesus of Good Friday.

Jesus on the cross is disabled in both a physical and a social sense.

A lot of times we focus too much on Resurrection Sunday or Easter, wanting to spiritually bypass the painful and hard parts of a faithful life and quickly move into the triumphalism of resurrection.

I also really relate to the abandonment on Good Friday.

I’ve definitely felt abandoned by churches I’ve been a part of and my friends that I’ve had within those churches who, from my perspective, didn’t care enough about disability to be willing to grow and learn together.

How does viewing God as disabled impact our understanding of who God is and our understanding of the world?

It reminds me that the ableism I have experienced doesn’t need to continue.

It brings a sense of empowerment to think about God as described in (the biblical books of) Daniel and Ezekiel, as sitting on a throne with wheels.

That sounds a lot like my wheelchair — it’s a shimmery, fiery, turquoise wheelchair like the one that I get around in.

On days when people attempt to pray me away or attempt to cure my disabled body, it reminds me that my disabled body is made in the image of the Divine.

- Kathryn Post is an author at Religion News Service.

- First published in RNS. Republished with permission.