Despite advances in cleaner water and safer indoor cooking, pollution remains the world’s leading environmental risk factor for disease and premature death, responsible for one in every six deaths, or 9 million premature deaths annually, according to a new report in The Lancet.

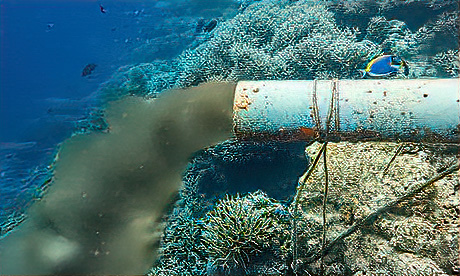

The report finds the majority of pollution-related deaths today come from what it calls modern sources, such as lead and chemical exposure and ambient air pollution primarily through the burning of fossil fuels, what the authors refer to as “the unintended consequence of industrialization and urbanization.”

The levels of pollution stemming from current economic models reflects “the throwaway culture” that Pope Francis has condemned and “certainly in no way constitutes good stewardship of our planet,” said Philip Landrigan, co-lead author and the director of the Global Public Health Program and Global Pollution Observatory at Boston College.

“We’re locked into this economic model, which is focused obsessively on short-term gain, on the gross domestic product,” Landrigan told EarthBeat. “We ignore natural capital, the ecosystems. We ignore human capital, people. We just burn through natural resources, we burn through people with the goal of creating ever-greater profit margins.”

Deaths from modern forms of pollution have risen 66% since 2000, the report stated, and have essentially wiped out gains in lowering mortality rates from water and household air pollution achieved through improved water and sanitation access and cleaner ways of household cooking and heating.

Overall, the death toll from pollution each year eclipses that from malaria, AIDS and tuberculosis combined is on par with smoking-related deaths and is more than the 6 million people who have died so far from the COVID-19 pandemic.

More than 90% of pollution-related deaths are located in low- and middle-income countries.

The findings, based on data from the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors study, were published May 17 in The Lancet Planetary Health, a subset of The Lancet medical journal, one of the world’s oldest and most widely respected medical publications.

The report’s authors said that despite its massive threat, pollution has been a largely “overlooked” problem and increasingly countries must work together in its mitigation.

“Pollution has typically been viewed as a local issue to be addressed through sub-national and national regulation or, occasionally, using regional policy in higher-income countries.

It is increasingly clear that pollution is a planetary threat, and that its drivers, its dispersion, and its effects on health transcend local boundaries and demand a global response,” the report’s authors said.

Landrigan, a pediatrician and epidemiologist, told EarthBeat that the world’s religions can play an important role in reducing global pollution by raising the moral and ethical dimensions of polluting the planet and also speaking directly with industry and corporate leaders.

“I think religious leaders have an opportunity here to step up … and say, ‘Hey, we simply can’t go on this way. We’ve got to move to a more sustainable, more circular economy where it isn’t just about more and more and more every day of the week.’ Because what we’re doing can’t go on,” he said. “There’s going to come a point of no return.”

In his 2015 encyclical, “Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home,” Francis bemoaned how “some forms of pollution are part of people’s daily experience” and referenced the millions of premature deaths resulting from such conditions.

Last September, the pope said in a message to the Council of Europe that all people have a right to a “safe, healthy and sustainable environment.”

The Lancet report follows up on a similar study in 2017, which also showed pollution responsible for 9 million annual deaths — a figure that has remained unchanged since 2015. What has changed are the sources driving mortality rates, with deaths from modern pollution sources having “increased substantially” over the past 20 years, the report said.

Overall, air pollution is responsible for 6.5 million deaths each year, with 4.5 million of those from ambient air pollution.

An estimated 1.3 million deaths are tied to water pollution; 1.8 million to lead and other chemical pollution, such as a group of chemicals known as PFAS and neonicotinoids, one of the most widely used types of insecticide; and 875,000 from occupational pollution. Modern sources account for roughly 5.8 million deaths, compared to 3.7 million from traditional sources that have historically been associated with extreme poverty.

The problem of pollution is most severe in low- and middle-income countries, according to the report, and especially acute in Asia and Africa, though in the latter historical forms of pollution are still the predominant causes of disease and death. More than 2 million people die annually from pollution in both China and India, though China has far fewer deaths (367,000) from household and water pollution than India (1.1 million). In terms of pollution deaths per 100,000 people, African nations of Chad (305), Central African Republic (299), Niger (241) and Somalia (237) are hit hardest, compared to the United States at 44 deaths per 100,000 people.

The report draws clear lines between pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss, calling them “the key global environmental issues of our time” whose solutions are “intricately linked” and mutually beneficial. One example it cites is to drastically cut emissions of short-lived climate pollutants, like methane, soot and hydrofluorocarbons that simultaneously pollute the air and capture heat in the atmosphere.

The report found that global chemical manufacturing has increased at a rate of roughly 3.5% per year, and will double by 2030. While gasoline and paint have been historical sources of lead exposure, people are encountering it more and more through poor recycling of car batteries, lead chromate added to spices and lead added to cookware and pots.

Rachel Kupka, a co-author of the report and executive director of the Global Alliance on Health and Pollution, said that lead exposure is especially harmful for children, with one in three children globally experiencing lead poisoning, which can hinder cognitive development.

“What we’re finding now is that lead, even very low levels of exposure, are contributing to a much higher burden of disease than anticipated before,” she told EarthBeat.

“It’s very bad news for people and the planet that air pollution is getting worse and chemical pollution is getting worse,” Landrigan said, adding, “We were hoping for better” results in the four years since the previous report.

One of the goals of that 2018 report was to persuade more countries to address what is widely seen as a neglected problem, especially in middle- and low-income countries. A major driver of pollution has been the industrialization and urbanization of nations, which as they rapidly work to build their economies predominantly have done so through burning fossil fuels.

“They’re taking a very short-term view and they’re making the mistake of investing in fossil fuels, which is, in my mind, a losing proposition because the costs of the pollution that fossil fuels produce outweigh any economic benefit that the fossil fuels produce,” Landrigan said.

In Laudato Si’, Francis urged countries that have developed through highly polluting sources to assist other nations to do so with cleaner energy sources.

“The same mindset which stands in the way of making radical decisions to reverse the trend of global warming also stands in the way of achieving the goal of eliminating poverty. A more responsible overall approach is needed to deal with both problems: the reduction of pollution and the development of poorer countries and regions,” the pope wrote. Continue reading

- Brian Roewe is NCR environment correspondent