The first thing I remember being taught about suicide is that it is selfish. And so in my middling Protestant childhood, while I did not worry about the eternal destiny of people who killed themselves, I did believe suicide was principally a moral failing.

In Catholicism, the situation was more complex.

Suicide was thought to be a mortal sin, of course.

But as a pastoral matter, in many places, Catholics who had committed suicide were denied funeral rites and burial in consecrated graveyards for concern of “public scandal of the faithful.”

In recent decades, as America has become more secular, it has also become more determined to address the rising rates of suicide.

In the United States, National Suicide Prevention Week engages mental-health professionals and the general public about suicide and culminates in World Suicide Prevention Day, sponsored annually on Sept. 10 by the World Health Organization.

Moving away from engrained assumptions about individuals’ selfishness and moral failings, both private associations and government agencies have portrayed suicide as a public-health problem to address through prevention strategies.

Accordingly, religious people and institutions today operate with a more sensitive and compassionate approach to suicide.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church now recognizes that “grave psychological disturbances” can reduce the moral culpability of suicide and no longer teaches that people who commit suicide necessarily go to hell: “We should not despair of the eternal salvation of persons who have taken their own lives. By ways known to him alone, God can provide the opportunity for salutary repentance.”

Even so, survey data shows that, in addition to demographic considerations, religion and proximity to suicide shape Americans’ attitudes on the subject.

A new study by Lifeway Research, an evangelical firm specializing in surveys about faith and culture, shows that more than three-quarters agree that suicide has become an epidemic.

Less than a quarter believe people who die from suicide automatically face eternal judgment, with Protestants now more likely than Catholics to believe suicide victims are damned.

People with evangelical beliefs are twice as likely (39%) than those without evangelical beliefs (18%) to think suicide leads to hell.

Still, 38% of those surveyed say people who commit suicide are selfish, with more religiously devout respondents likelier to agree.

The Lifeway data suggests Americans consider suicide a serious social problem, with 4 in 10 saying it has claimed the lives of a friend or family member.

It’s good for all involved that religious traditions, aided both by pastoral experience and insights from psychology and psychiatry, have adopted more compassionate beliefs about suicide.

But many faithful still do not understand that suicidality is not a sign of rejection by or of God, but rather a complex result of trauma, deep emotional disturbances and brain-chemistry anomalies.

And even fewer have the spiritual tools to grapple with the reality that suicidal ideation, as with all forms of self-harm, is a spectrum.

It may be as benign as passive, low-grade self-sabotage instincts or a one-off passing urge in a moment of distress. Or it can be as profound and intrusive as active wishes to die, whether compelled by delusions and psychoses or simply inescapable emotional torment.

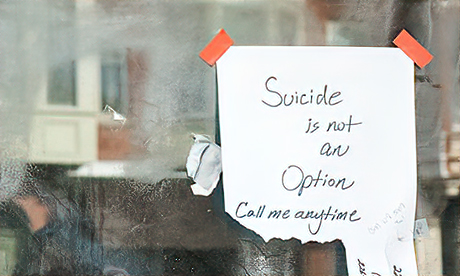

Suicidal people need help, not condemnation. Yet even when faith traditions offer compassion in Scripture, doctrine or policy, it matters little to a suffering soul who experiences religiously fueled rejection by family members or friends.

I have experienced suicidal people who, in part due to active or latent faith commitments, summoned determination to keep themselves alive.

Likewise, I have heard stories of crushing pain from people whose own families essentially punished their openness about suicidal ideations with threats that God, the church and their family would abandon them.

Suicide is a near-universal phenomenon throughout history and around the world.

It is deeply related to religious themes, including meaning, hope, honour and suffering. But religious groups alone rarely have the capacity, competence or inclination to reduce suicide on a societal scale.

Millions of people contemplate suicide every year.

Religion at its worst sees them as sinners deserving of condemnation.

At their best, faithful people and institutions compassionately accompany people contemplating suicide toward connection, openness and treatment.

And when that fails, clergy and congregations must point to a God gracious and loving enough to hold not only the souls of people who take their own lives, but also to comfort and heal all who love and miss them.

- Jacob Lupfer is a writer in Jacksonville, Florida.

- First published in RNS. Republished with permission. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.

Where to get help

Need to Talk? Free call or text 1737 any time to speak to a trained counsellor, for any reason.

Lifeline: 0800 543 354 or text HELP to 4357

Suicide Crisis Helpline: 0508 828 865 / 0508 TAUTOKO (24/7). This is a service for people who may be thinking about suicide, or those who are concerned about family or friends.

Depression Helpline: 0800 111 757 (24/7) or text 4202

Samaritans: 0800 726 666 (24/7)

Youthline: 0800 376 633 (24/7) or free text 234 (8am-12am), or email talk@youthline.co.nz

What’s Up: online chat (3pm-10pm) or 0800 WHATSUP / 0800 9428 787 helpline (12pm-10pm weekdays, 3pm-11pm weekends)

Kidsline (ages 5-18): 0800 543 754 (24/7)

Rural Support Trust Helpline: 0800 787 254

Healthline: 0800 611 116

Rainbow Youth: (09) 376 4155

If it is an emergency and you feel like you or someone else is at risk, call 111.