In 1987, the Court of Appeal came up with “principles of the Treaty” as part of its findings in the “Lands” case.

The principles were based on the assumption that the two Treaty texts were not translations of each other and didn’t convey the same meaning. Therefore, the court felt free to explore what the judges thought was the “spirit” of the Treaty.

We really need to look at that again because it’s no longer acceptable, historically speaking, to say that the Treaty texts are completely different from each other.

The reason I think it’s no longer acceptable is because of research by legal historian Ned Fletcher, which I supervised over a period of seven years. His thesis sets out a compelling and thorough argument for reconciling the Māori and English texts of the Treaty.

It’s a brilliant piece of scholarly research with massive footnotes and citations to every conclusion that is made. It’s a long read, but if people want to just look at one page, it’s page 529 where Ned summarises why we should assume that the text in Māori and the text in English said roughly the same things.

In particular, the thesis demonstrates that both texts guarantee the continued rangatiratanga and authority of Māori in New Zealand.

It argues that the cession of sovereignty, as understood in 1840, did not impose English law on Māori. Rather, it assumed that tikanga, as the law in operation for the Māori world, would continue.

Historian Ruth Ross, in her famous essay in 1972, was quite correct to say we must stop looking at the English text as the only text of the Treaty. She reminded us that New Zealand in 1840 was a te ao Māori world, in which Māori was the relevant language. Te Tiriti therefore remains the paramount text because that’s the version that Māori talked about at hui and then signed.

But along with that reminder went her second statement, which was that the English text was purposefully different from the Māori text. She argued that the English version of the Treaty was deceitful and, therefore irrelevant.

If you look only to Te Tiriti because you believe the English text was flawed and intended to improperly gain Māori consent, then the whole transaction becomes a trick and a fraud.

Whereas, if we look to what I now think is the historically-correct context — the Treaty as a genuine attempt at a relationship-building exercise — then it opens the possibility of doing things better in our society today. We can proceed based on the original bargain, not based on a 1987 reinterpretation of the bargain.

We need to get back to the original understanding. That will give us some good hints about how we can solve some of our major issues like cleaning up our rivers and natural environment, looking after our precious places, deciding customary rights, and the way in which water is allocated and cared for. Continue reading

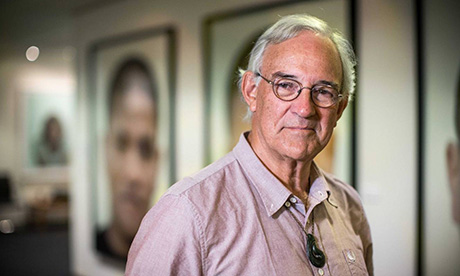

- Dr David V Williams is a Professor Emeritus at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland. He was a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, and his PhD is from the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania where he taught in the 1970s. He has tertiary qualifications in history, law and theology, and continues to work as an independent researcher on Treaty of Waitangi issues.