As Poles move away from the church – particularly the urban young, and also some older believers in the Catholic small-town heartlands – a deeply religious country wrestles with its own identity.

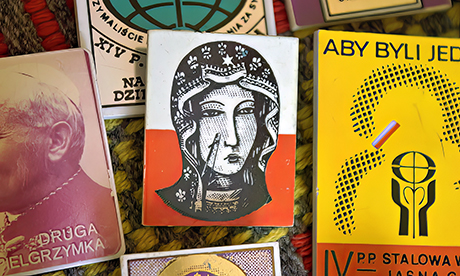

The Black Madonna of Częstochowa looks much like other Eastern religious icons, with its deep golden halos and sombre colour palette.

But the painting, whose origin is still unknown, has come to represent not only Catholicism in Poland, but also Polish national pride.

Each year, more than 120,000 pilgrims make the journey to the shrine to pay homage to an image once described as the “Queen of Poland”.

In the late 1980s, the face of the Black Madonna appeared on Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa’s lapel.

Pilgrims risked their lives to travel on foot to the monastery during the German Nazi occupation of Poland, and a rosary made from concentration camp beads is on display as one of many relics of the nation’s painful past.

An attempted robbery of the icon in 1430 left two slashes on the Virgin Mary’s face, reminding its viewers of what the icon and its home country have been through.

For Renata Zabłocka, 49, raised in a Catholic family in small-town southeastern Poland, the church was the centre of public life. “Everything revolved around the church,” she says – cultural events, social life and shared values.

But now she has stopped attending weekly mass on Sundays, even though she still describes herself as a believer in God. She says she felt “forgotten and judged” by the church, which used to be her main mechanism of support, after she divorced her husband of 20 years last year.

“When I needed help, no one came to check if I was okay,” she says. “I can’t say that I’m no longer faithful, but my thinking on certain issues has changed.”

Poland has been experiencing increasing scepticism towards the Catholic church in the past few years. That phenomenon is most visible among the young and in big cities.

According to data from CBOS, a state research agency, today less than 25% of young Poles regularly practise their religion, down from around 70% in the early 1990s.

“In big cities like Warsaw, church attendance is around 20% of what it once was”, says Franciszek Mróz, a professor of geography at the Pedagogical University of Kraków specialising in religious tourism. But he also notes that, even in small villages, that figure is around 80%, indicating a decline in conservative rural areas.

However, falling involvement with the Catholic church as an institution does not necessarily mean that Poles are losing their faith in God.

CBOS data show that, among all Poles, weekly religious practice has declined from almost 70% in the early 1990s to 42% now. The church’s own figures tell a similar story. Read more