To properly understand McElroy’s radical inclusion proposals, it is necessary to situate them in the context of the pastoral ecclesiology and synodal process advocated by Pope Francis.

The pastoral ecclesiology of Pope Francis is the background for McElroy’s essay.

Francis envisions a consciously expansive church characterized as a mother that excludes no one. A priority for the church today is to look forward, not backwards.

Francis’ pastoral ecclesiology accentuates what people share rather than what divides us.

He preaches mercy, compassion and forgiveness rather than stern admonishments and condemnations.

Charity must prevail in all things.

He echoes Pope St. John XXIII: “In essentials, unity; in doubtful matters, liberty; in all things, charity.”

Francis insists that we must allow ourselves “to be surprised by God.”

In Evangelii Gaudium, Francis calls for a far-reaching “pastoral and missionary conversion of the church in our time,” a reexamination of attitudes, structures and church practices in light of their capacity to effectively proclaim the love and mercy of God as shown in the Gospel.

Dialogue (synodality) within the church is an essential component of this examination.

The pope’s vision resonates with the opening lines of Vatican II’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World:

“The joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially whose who are poor or afflicted, are the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ.”

The two synods on the family (2014 and 2015) addressed a wide range of pastoral issues, including pastoral care for the divorced and remarried and those excluded from the sacrament of the Eucharist.

Francis is not advocating

a pastoral compromise

regarding church teaching

but rather an authentic interpretation

of the doctrine

relating to real human persons

and concrete situations.

These concerns have been longstanding for Francis. He has no desire to reverse the church’s teaching on the indissolubility of marriage.

Rather, his intention is to root the church’s teaching more firmly within the scope of Christian mercy.

He would like the church to consider that there are at least some divorced and remarried couples who, in situations where renouncing their second marriage, would only compound the harm caused by the failure of the first marriage by requiring breaking the current familial commitment.

Is it not possible, Francis asks, to find signs of grace and hope in the second marriage and thereby acknowledge the value of the Eucharist for such couples as a “medicine of mercy”?

Francis’ hope is to negotiate the tension between the normative claims of church doctrine and the pastoral reality.

He refuses to see doctrine and pastoral practice as mutually exclusive options and simply resolves ecclesiological tensions prematurely.

In his address at the conclusion of the Extraordinary Synod on the Family in October 2014, he warned against “a temptation to hostile inflexibility, that is, wanting to close oneself within the written word … and not allowing oneself to be surprised by God… From the time of Christ, it is the temptation of the zealous, of the scrupulous, of the solicitous and of the so-called – today – ‘traditionalists’ and also of the intellectuals.”

His point is clearly made when he addressed the text of Humanae Vitae:

“The object is not to change the doctrine, but it is a matter of going into the issue in depth and to ensure that the pastoral ministry takes into account the situations of each person and what that person can do.”

He desires that the church and confessors “be very generous” in dealing with individual couples’ “pastoral situations.”

He is not advocating a pastoral compromise regarding church teaching but rather an authentic interpretation of the doctrine relating to real human persons and concrete situations.

His desire might be fulfilled by the church moving beyond a narrow analysis of an act to consider the entirety of the human person and the context.

Pope Francis calls the church to meet people “in the streets,” ministering to their concerns and attending to their wounds.

He calls for a “pastoral connaturality,” as theologian Richard Gaillardetz terms it, to discern how the church’s doctrine can best be employed to exemplify God’s solidarity with the poor and suffering and be generous with the mercy of God.

The emphasis on mercy is the hallmark of the Francis papacy. His naming of the church as a “field hospital” is especially addressed to priests who must be men of mercy and compassion, close to his people, and servants of all.

“Whoever is wounded in life, in whatever way, can find in him attention and a sympathetic ear,” he told parish priests in Rome in 2014. Continue reading

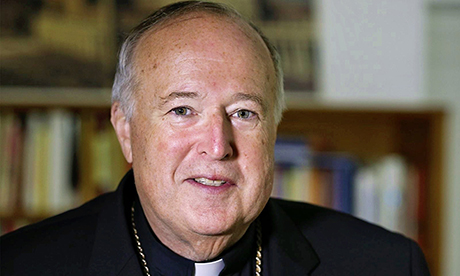

- Gerald D. Coleman is a retired professor of moral theology, St Patrick’s Seminary & University, Menlo Park, California, and Graduate Department of Pastoral Ministries, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, California. As long-ago he was the moral theology professor of now-Cardinal Robert McElroy,