I wanted to start by acknowledging that what the Church calls Good News and what journalists call good news are entirely different things.

The Christian Gospel, which is a word meaning, ‘good news’ – is that the Creator of all things, God, so loved the world that He gave His only Son so that all who believe in Him should not perish but have life now and eternally.

To put it another way, God who is Just provides salvation.

And what that means in practice, is a worldview that trusts the faithfulness of God.

At the same time, Christians live in a God-created community, the Church – and that is the rub.

The Church, being full of human beings, is full of those who go wrong.

The Church often seeks to speak truth to power, but we must recognise as different bits of the Church, and, speaking as the Church of England, our own power as well as our immense failures and sins.

And therefore, we should welcome the challenge and scrutiny from the media that is part of living in a democratic society. Having spent a good deal of my life travelling in places that don’t have those freedoms, I know which I prefer.

When I started this job just over 10 years ago, the media landscape, even that short period ago looked different. It has become faster, more complex, more driven by social media.

In an age of misinformation, distraction, and the competition of noise with truth, it is ever more difficult for journalists to do their job. The best account of that I’ve heard recently was a series of podcasts by Jeremy Bowen, that some people may have seen – they make long journeys go very quickly!

My approach to the media has developed over 10 years.

I take more risks, deliberately rather than accidentally.

I try to engage, and I recognise the vital importance of seeking to communicate well what the Church is doing and what we actually care about.

I tried to say yes to as many media outlets as possible, especially the local and the regional.

I know how successful they are because they are deeply embedded in the community.

I have a very strong memory of a visit to a particular diocese in the province of Canterbury and being asked – did I enjoy travelling on buses, and what I thought about the bus timetable in that particular town?

They were certainly embedded in the community.

And they do marvellous things, especially at the local level, being immensely stretched and having had an incredibly hard time in the last 10 years.

I actually quite enjoy interviews, believe it or not, although they make me very nervous.

I could sit on the sidelines, and I’m very tempted to do so very often, knowing that when anything is said in public by anyone, it will be analysed and instrumentalised.

One of the relatively few things I’m looking forward to in my eventual and long distant retirement is being able to read the paper without worrying about whether I’ll see my own name in any context at all.

There are two aspects to any religious figure’s involvement in the media.

First, you’re reported on – for example, after making a speech on the Illegal Migration Bill.

Secondly, there is the context of engaging with the media proactively and giving interviews or engaging on social media.

There’s a difference.

So if we start off by engaging with the media, why do it?

The greatest single reason is that Christian faith claims truth.

For Christians, truth is not a concept, it is a person – Jesus, not an idea.

When in John, Chapter 14:1-6, one of Jesus’s disciples expostulates with him when he says, you know where I’m going, and the disciple says to Jesus, I haven’t the faintest idea what you’re talking about.

And Jesus replies, I am, the Way, the Truth and the Life.

When Pilate, at his trial says what is Truth?

He’s asking the wrong question.

He should ask who is Truth – and Truth is standing before him, beaten and bloodied, and looking anything but impressive.

When I was interviewed by Alastair Campbell several years ago, we talked about his famous phrase ‘We don’t do God’.

And we talked about the fact that even if New Labour didn’t do God, God still does us and, for that matter, New Labour.

God’s faithfulness and providence is an embracing worldview that is not a private hobby but a universal principle, recognised or not.

Terry Pratchett, whose books I found enormously amusing, has a book called ‘Small gods’ and the size of the god depends on how many worshippers they have.

Well, it’s clever and amusing, but it’s false.

God does not need worshippers; people and creation need God.

If we take the Illegal Migration Bill, for example, I find myself reminded of the passage in Matthew 25:31-46, which is about the Last Judgement.

It concerns two groups of people who unknowingly live in a way that either honours or fails to honour God’s commands for our way of life in the world.

It echoes what’s often called the Nazareth manifesto.

In Luke chapter 4:16-21, these two groups of people, the sheep and the goats they’re called, they either feed the hungry or fail to do so, they nurse the sick, they visit the prisoner, and as we think about the Illegal Migration Bill, they welcome the stranger – or they fail to do so.

The second group lived as though it didn’t matter.

The first group is welcomed by Christ to eternal life.

The second group have to face the terrible consequences of living for their own interests, as though those in need did not matter.

Churches are active in this world and in its concerns because they see God being active in this world. And many of those people who call for our help are Christians.

Churches are over 2 billion strong in every country around the world, even the Anglican Communion spans about 80 or 85 million people across 165 countries. And the typical Anglican is a woman in her 30s in Sub Saharan Africa, likely living in an area of conflict or persecution who lives on less than $4 a day.

Anglicans live in the hills of Papua New Guinea or, they work in the streets of the City of London, or in the banks and the dealing rooms.

So when I talk about migration or about poverty, or conflict or trade or natural disaster, or climate change or social justice, it isn’t a hobby or a way of filling the otherwise empty days.

When I talk about these things, I see in my mind’s eye the people I know and love around the world.

The people I call brother and sister because we belong to the same family in Christ.

Being part of that changes everything. Religion isn’t a bolt on to our lives.

It’s not an app you can download into the human software.

It’s the entire operating system.

It’s the prism through which we see everything else.

And then this country may be becoming more secular or not, as the case may be.

At the Lambeth Conference

we talked extensively;

we spent two hours on sexuality in 10 days,

on everything else,

slavery and justice, suffering.

But we chose to love one another

despite our differences.

The world as a whole is not, 80% of the world population is religious, and it’s going up, not shrinking.

So when we talk about religion or religious people, we’re not studying some endangered exotica under the microscope.

Of course, not all of that 80% are Christians, not even the majority.

And our relationship with other faiths is very important, as we saw at the Coronation.

We work closely with other faiths not just out of a deep sense of hospitality, which is arising from our understanding of the nature of God.

But also because other religious groups have a religious perspective that shapes how they see the world.

The Big Help Out, a volunteering initiative on the Monday after the Coronation, was endorsed by religious groups.

And you may have seen the images in the news: Muslims, Jews, Christians, Sikhs, and others of no faith and of other faiths got together.

It involved 7.2 million people in this country, well over 10% of the country.

In your reporting,

don’t forget the millions of people

and the incredible stories

that the Christian church

and even the Church of England represent.

It was a project started by the Together Coalition, which I chair, and on that day, Caroline and I served lunch together at a homeless charity.

Going back finally to what I said at the beginning, about ‘good news’.

At the Lambeth Conference of Anglican Bishops from around the world, which happened for the first time in 14 years last summer in Canterbury, I joined journalists who were covering it at a reception.

During that gathering, I said, yes of course we know there are stories about deep disagreements over sexuality that they would want to report on, and rightly so; they’re important issues, and they are a good story.

But please remember that, at that gathering, I said there are people from war-torn countries and nations suffering from famine and drought, people who have literally just fled oppression and brutality, and people who have come from refugee camps.

Bishops represent the most vulnerable people in the world.

At the Lambeth Conference we talked extensively; we spent two hours on sexuality in 10 days, on everything else, slavery and justice, suffering.

But we chose to love one another despite our differences.

Please, in your reporting, don’t forget the millions of people and the incredible stories that the Christian church and even the Church of England represent. Because I think that is also good news for all its faults, both for journalists and Christians.

So now, as I finish, I’d like to turn the tables and ask a couple of questions of you.

How do you communicate the worldview of religious people, as well as the fact in a way that just doesn’t put their religion in a part of their lives?

And, can you help me through your questions and your comments, understand better, how we can communicate with you?

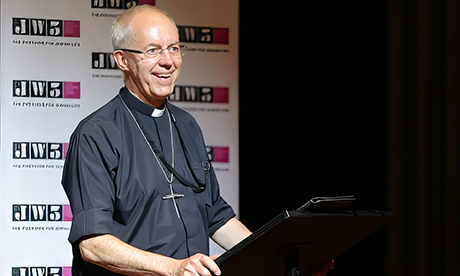

- Archbishop Justin Welby is Archbishop of Canterbury

- Speech delivered at Religion Media Festival