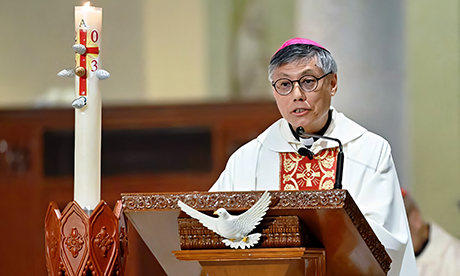

The appointment of Hong Kong’s Bishop Stephen Chow Sau-yan as a Cardinal a little over a year and a half after he began his Episcopal ministry in the city is yet another sign of Pope Francis’ devotion to Asia and to China in particular.

It is also a sign of the Holy Father’s commitment to making the Consistory truly global and to reaching out beyond the European foundations of the Church to the world.

It gives Hong Kong three Cardinals — a rare privilege for any diocese — as Cardinal-elect Chow takes his place alongside Cardinal John Tong and the courageous 91-year-old Cardinal Joseph Zen.

For these reasons, his appointment is welcome and should be celebrated by Hong Kong Catholics.

And the fact that Pope Francis has appointed Hong Kong’s Bishop Chow as the new — and latest — Chinese Cardinal, rather than Beijing’s Archbishop Li, the head of the Catholic Patriotic Association, shows that there is still recognition within the Vatican of Hong Kong’s certain uniqueness. This is welcome.

However, Cardinal-elect Chow is no Cardinal Zen or a Cardinal Kung.

The Vatican’s motivation for conferring the red biretta on his head raises some alarm bells.

From everything I have heard from Hong Kong Catholics, Chow is a good, spiritual and pastoral leader.

When his appointment as the city’s bishop was announced, I welcomed it because I understood that while he was unlikely to be a vocal cheerleader for democracy; at the same time he was unlikely to be Beijing’s stooge.

He appeared to be the compromise candidate acceptable to all — to pro-democracy Hong Kongers, to the pro-Beijing camp, and to ordinary Hong Kong Catholics.

I was hopeful that he would have the right mix of pastoral skills, wisdom and spirituality.

Over the past six months, however, it has become clear that — perhaps under pressure from Beijing, local Hong Kong authorities, the Vatican and the overall circumstances, or perhaps as a result of his natural instincts — Chow has taken a worryingly soft, conciliatory, compromising approach towards the Chinese Communist Party regime and its crackdown in Hong Kong.

To be frank, I never expected Chow to speak truth to power with the bluntness and boldness of Cardinal Zen.

But nor did I expect him to visit Beijing and return, calling his flock to show their patriotism.

True patriotism — love of country — is something most of us would accept.

But you have to be naïve to not realize that in today’s China, an official call to “love your country” is easily confused with loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party regime — especially in Hong Kong today, with the so-called oaths of patriotism, which public servants are required to swear.

Cardinal Zen — whose Episcopal motto is Ipsacuraest (“He cares about you,” from 1 Peter 5:7) — received his red biretta in 2006 from Pope Benedict XVI, who also appointed Cardinal Tong six years later — whose motto is Dominus Pastor Meus (“The Lord is my Shepherd”).

Back in 1979, Pope St John Paul II created Shanghai’s Bishop Ignatius Kung Pin-mei a Cardinal in pectore. His motto was Ut Sint Unum Ovile Et Unus Pastor (“That there may be one fold and one shepherd”).

Chow’s Episcopal motto is Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam (“For the greater glory of God”).

All four mottos are of course deeply inspiring.

But while it is clear that Cardinal Zen was honoured for his commitment to justice and human rights, Cardinal Kung was recognized for his 30 years in jail and his lifelong commitment to religious freedom.

Even Cardinal Tong — although he was milder-mannered and more inclined to compromise — called for the release of Chinese Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo and all underground clergy in jail in China in his Christmas message in 2010.

It is unclear where exactly Hong Kong’s new Cardinal Chow’s conscience and voice lie.

On the evidence, it would seem that his red biretta is an affirmation of or reward for his soft stance towards Beijing, which is a break from the legacy of Zen, and Kung in particular, which is in keeping with the Vatican’s current approach.

So what is the Vatican’s approach? It appears to be a policy of appeasement and kowtow.

The Vatican-China deal signed in 2018, renewed in 2020, and again in 2022 — each time in extraordinary secrecy, with no transparency, scrutiny, or accountability — has bought the silence of the Holy Father over grave atrocity crimes and human rights violations in China and amounts to the Reichskonkordat of today.

In summary, it has resulted in a situation where a Pope who speaks out more often than many of his predecessors on injustice and persecution in one corner of the world or another — almost every Sunday as he prays the Angelus — is yet continuously and conspicuously silent over one very large part of the world.

Pope Francis is the first pontiff in the past several decades not to meet His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

He has said almost nothing — and nothing meaningful — on the genocide of the Uyghurs, and been silent in the face of the dismantling of Hong Kong’s freedoms, forced organ harvesting, and the persecution of Falun Gong and Christians in China.

He has said nothing of significance that could be reassuring to Taiwan.

The latest, and perhaps worst, example of Rome’s kowtowing to Beijing is the news last week that Pope Francis has confirmed the appointment of Bishop Joseph Shen Bin as Bishop of Shanghai.

This appointment was made by Beijing, without consulting Rome, in total violation of the Vatican-China agreement earlier this year.

This is at least the second violation of the agreement by Beijing, following the illicit appointment by China of an auxiliary bishop in Jiangxi, in a diocese not recognized by the Holy See.

That drew a mild complaint from the Vatican, which accused Beijing of breaching the agreement.

But the news that Pope Francis now confirms the Shanghai appointment is a hammer blow to any thought that the Vatican might be waking up.

Instead, it is an indicator that Rome’s kowtow policy will continue.

I know that within the body of Church teaching, there is room for interpretation and there is a need for a wide range of charisms.

We need those like Cardinal Zen and Cardinal Kung who stand up uncompromisingly for human rights and justice, and we need others — perhaps like Hong Kong’s new Cardinal Chow — who pursue justice through dialogue.

Justice and peace go together. Dialogue and reconciliation have a key part to play, alongside truth and accountability. But what we can never do is have one without the other. To lose any one of these is like amputating a limb.

I pray Chow’s Episcopal motto will lead to new heights for Hong Kong. But I tend to think that the motto of Myanmar’s Cardinal Bo — Omnia Possum in Eo (“I can do all things in Him) — is a bit more ambitious.

There is only one place to genuflect: at the altar of God. Rome should never be genuflecting at the gates of Zhongnanhai.

- Benedict Rogers, a human rights activist and writer, is the co-founder and chief executive of Hong Kong Watch, and Senior Analyst for East Asia at Christian Solidarity Worldwide, a rights organisation specialising in freedom of religion or belief.

- First published in UCANews.com. Republished with permission.