Without doubt, the best line to emanate from the Synod on Synoldality is “Excuse me, Your Eminence, she has not finished speaking.”

That sums up the synod and the state of the Catholic Church’s attitude toward change.

In October, hundreds of bishops, joined by lay men and women, priests, deacons, religious sisters and brothers met for nearly a month in Rome for the Synod on Synodality.

At its end, the synod released a synthesis report brimming with the hope and the promise that the church would be a more listening church.

Some 54 women voted at the synod. Back home, women are still ignored.

Why?

It is not because women quote the Second Vatican Council at parish council meetings. It is because too many bishops and pastors ignore parish councils.

It is not because women of the world do not write to their pastors and bishops. It is because without large checks, their letters are ignored.

The Synod on Synodality was groundbreaking in part because it was more about learning to listen.

It was more about the process than about results. Its aim was to get the whole church on board with a new way of relating, of having “conversations in the Spirit,” where listening and prayer feed discernment and decision-making.

Even now, the project faces roadblocks. At their November meeting this week in Baltimore, U.S. bishops heard presentations by Brownsville, Texas, Bishop Daniel Flores, who has led the two-year national synod process so far.

His brother bishops did not look interested.

To be fair, some bishops in some dioceses, in the U.S. and other parts of the world, are on board with Pope Francis’ attempt to encourage the church to accept the reforms of Vatican II, to listen to the people of God.

Too many bishops are having none of it

The synod recognized the church’s global infection with narcissistic clericalism.

It said fine things about women in leadership and the care of other marginalized people. Yet the synod remains a secret in many places. Its good words don’t reach the people in the pews.

Ask about synodality in any parish, and you might hear “Oh, we don’t do that here.” You are equally likely to hear “When I” sermons (“When I was in seminary,” “When I was in another parish”), and not about the Gospel.

Folks who were excited by Francis’ openness and pastoral message just shake their heads.

The women who want to contribute, who want to belong, are more than dispirited.

They have had it.

And they are no longer walking toward the door — they are running, bringing their husbands, children and chequebooks with them.

In the Diocese of Brooklyn, it was recently discovered that Mass attendance had dropped 40 percent since 2017.

It is the same in too many places.

The reason the church is wobbling is not a lack of piety.

It is because women are ignored.

Their complaints only reach as far as the storied circular file.

What do women complain about?

Women complain about bad sermons, as discussed. Autocratic pastors. And the big one: pederasty.

If truth be told, women do not trust unmarried men with their children.

Worldwide, in diocese after diocese, new revelations continue. Still.

Many bishops and pastors understand this.

Francis certainly does, but he is constrained by clerics who dig their heels into a past many of them never knew.

More and more young (and older) priests pine for the 1950s, when priests wore lace and women knew their place. That imagining does not include synodality.

Will the synod effort work?

Francis’ opening to women in church management is promising. Where women are in the chancery, there is more opportunity for women’s voices to be heard. No doubt, a few more women there could help.

Getting women into the sacristy is trickier.

While it seems most synod members agreed about restoring women to the ordained diaconate as a recognition of the baptismal equality of all, some stalwarts argued it was against Tradition.

Still, others saw the spectre of a “Western gender ideology” seeking to confuse the roles of men and women.

So, they asked for a review of the research. Again.

Women know the obvious: Women were ordained as deacons.

There will never be complete agreement on the facts of history, anthropology and theology. Women have said this over and over.

If there is absolute evidence that women cannot be restored to the ordained diaconate, it should be presented, and a decision made.

The women have finished speaking about it.

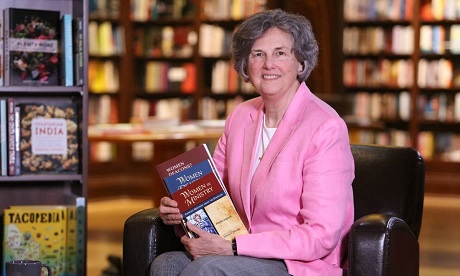

- Phyllis Zagano is an author at Religion News Service. She has written and spoken on the role of women in the Roman Catholic Church and is an advocate for the ordination of women as deacons.