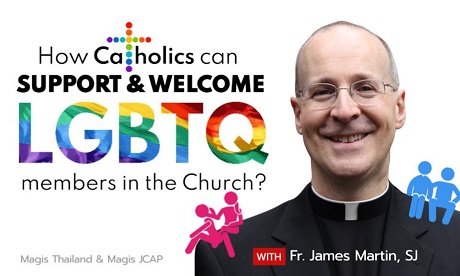

Inside one of the many skyscrapers in the center of Manhattan, James Martin (pictured) heads to his office at America, the Jesuit magazine where he is an editor.

Martin’s workspace is filled with objects that evoke his personal journey as a Jesuit priest who has worked with gang members in Boston as well as refugees in Kenya.

Next to his computer, there’s a photo of him conversing with Pope Francis during a meeting in 2019 at the Vatican. This was the first of four one-on-one encounters the two Jesuits have now had.

“It was one of the highlights of my life,” Martin recalls.

“I am not a cardinal, archbishop, bishop, or even a university president. Why would a pope want to meet me?”

Only one of many voices

He knows the answer. At 63 years old, the American Jesuit is one of the leading advocates for including LGBT people within the Catholic Church.

He has both the trust and ear of Francis.

In 2017, the pope appointed him as a consultant to the Dicastery for Communication. And last year, he asked him to participate in the Synod assembly on the future of the Church.

Ever since the publication of Fiducia supplicans, the controversial declaration the Vatican’s doctrinal office issued last December that allows priests the possibility of blessing same-sex couples, Martin proudly states he has done so four times.

“I am just one of many voices speaking to the pope on this issue,” he says, downplaying his role in this development.

“What does this community need to do to be recognised by the Church?”

The LGBT cause has not always been central for Martin.

Before being ordained a priest, this child of a French teacher and a businessman pursued a career in accounting and human resources at the American conglomerate General Electric.

“I was a yuppie,” he says. “I made a good living, lived in New York, went to nightclubs, and spent a lot of money.”

But he grew weary of that lifestyle after a few years.

He saw a documentary about the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, but he didn’t even know what a monastery was.

In the end, he decided to become a Jesuit.

He first began writing about LGBT Catholics in the 1990s in the pages of America because “the issue was little addressed at the time”.

He faced his first controversy in 2000 when he wrote an article about gay priests. But it wasn’t until sixteen years later that he decided to make recognition of LGBT people the focus of his ministry.

The turning point was the death of 49 people on June 12, 2016 at “Pulse”, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

“Very few bishops spoke out after this shooting, the deadliest in the country’s history. And even fewer used the word ‘gay’,” Martin says.

“I thought to myself – ‘what does this community need to do to be recognised by the Church?’ Is dying not enough?”

After the nightclub shooting, he began participating in conferences, appearing in major news media, and writing books like Building a Bridge (HarperOne, 2018).

His aim was to urge the Catholic Church to “listen” to its LGBT members rather than “treat them as sinners who need to be scrutinised for life”.

He even became the subject of a 2021 documentary produced by the famous director Martin Scorsese.

And since 2022, he has been running “Outreach”, a website affiliated with America that is dedicated to LGBT Catholics.

“I’m not one to seek controversy”

His notoriety has earned him enemies, including many bishops, who accuse him of wanting to distort Catholic teaching.

“Jesus welcomed the marginalized, that’s what I do,” he says in defense of his work.

“I’m not one to seek controversy. I would prefer to write about saints and prayer, but I’ve gotten used to being hated.”

While he sees Fiducia supplicans as a “huge” advancement, he does not believe it marks a step towards recognising homosexual unions.

“LGBT Catholics have accepted that this point will not change. All they want is to be treated as human beings,” he says.

“By excluding these people, we are also closing the doors of our churches to their parents, siblings, and friends. In the past, they would have sought their place within the Church. Now, they prefer to leave.”

- First published in La Croix International

- James J. Martin SJ is an American Jesuit Catholic priest, writer, and editor-at-large of the Jesuit magazine America and the founder of Outreach.