The twentieth century saw major advances in technology and communications, economy and human rights. It was also the bloodiest century in history.

Think of the mass deportations, starvation and extermination of perhaps 14 million people in Stalinist Russia and even more in Maoist China; the Holocaust of 6 million Jews under the Nazis, as well as gypsies, the handicapped and others; the massacres in Cambodia, Rwanda, Srebrenica and Dafur.

Altogether tens of millions were killed or tortured in attempts to exterminate whole peoples and cultures.

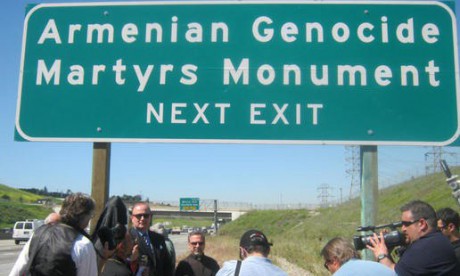

But historians generally agree that first great genocide of the modern era – the model, in fact, for some subsequent ones – was “the great crime” of the Ottoman Empire, in which 1 to 1.5 million Armenian, Assyrian and Greek Christians were killed.

Where, we wonder, was God in all this?

Christians believe God is all-powerful, all-knowing and all-good – indeed, He is goodness itself – and so never directly intends or causes evil. Human beings, on the other hand, all too often choose evil: individually they commit sins, large or small, and in concert with others they sometimes commit grave atrocities.

Human beings, not God, are responsible for those misdeeds and the terrible effects on innocent victims.

Yet, still we wonder why God permits such things, even if He does not directly will them. One traditional answer (from St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas) has been: that even when God allows evils to be perpetrated, He ensures some greater good can come from them.

That can be hard to see at the time – hard, even a century later. But eventually we see the divine hand bringing good out of evil and realize things might otherwise have been even worse. We witness the blood of martyrs seeding the Church and experience divine grace conquering hatred and cruelty with reconciliation and solidarity. As the Portuguese saying goes, God writes straight with crooked lines. Continue reading

Sources

- Archbishop Anthony Fisher, ABC Religion & Ethics

- Image: United Armenian Council