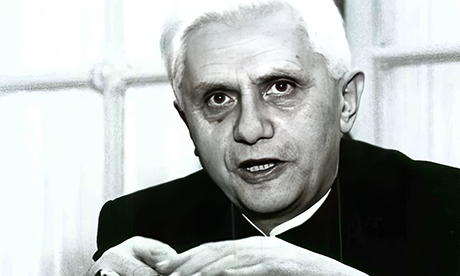

I first met Joseph Ratzinger in June 1994 when he was the cardinal prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

No, I was not being interrogated by the Grand Inquisitor.

This was long before I got in trouble with the Vatican as editor-in-chief of America magazine.

I was in Rome to interview him and other church officials for my book, “Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.”

I almost missed the interview.

Cardinal Ratzinger was sick the day of our appointment.

When I arrived, I was asked whether I wanted to meet with the congregation’s secretary.

I agreed, figuring it was better than nothing.

When I was ushered into his presence, I hadn’t gotten a word out before the secretary, Archbishop Alberto Bovone, assaulted me with questions: “Who are you?” “What are you doing here?” “I will decide whether you can see Cardinal Ratzinger.”

“But the cardinal already agreed to see me,” I stuttered.

That meant nothing to him; he demanded a list of questions I was going to ask.

He then assigned a young Dominican to interrogate me.

Jesuits being interrogated by Dominicans working for the Inquisition has a long and unhappy history.

On the other hand, Dominicans have also come to our rescue.

When Lorenzo Ricci, the Jesuit superior general died in 1775 after being imprisoned in Rome’s Castel Sant’Angelo by the pope, the top Dominican was the only one willing to preside at his funeral.

The tradition has continued ever since.

In any case, I was handed over to the Dominican, who, it seemed, was already on my side. During my interrogation by Bovone, he made faces and rolled his eyes behind the secretary’s back.

Rather than interrogate me, he advised me on what to do. “Write a letter to the cardinal. Explain that you are leaving at the end of the week and that you would like to meet with him for 15 minutes.”

I wrote the letter as soon as I got back to my room, faxed it to the CDF and got a new appointment.

Ratzinger agreed to meet with me in the afternoon when Vatican offices are usually closed.

The interview went more than an hour.

I learned a lot about Ratzinger before the interview even began. He was kind and willing to go out of his way to help a young scholar, even at a time he was not feeling well.

On the other hand, having a bully as his No. 2 man showed either blindness on Ratzinger’s part or an unhealthy dependence on people who, though loyal, were not fit for their jobs.

Neither as prefect nor as pope was he good at choosing his subordinates.

When we sat down for the interview, Ratzinger asked whether I wanted to do it in German or Italian.

With a panicked voice I said, “English would be much better.”

He agreed, saying “My English is very limited.”

In fact, it was excellent.

Only once during the interview did he struggle for a word.

He told me that he was at first undecided whether to accept the position as head of the congregation. Pope John Paul II had to ask him three times before he said yes.

“Give me time, Holy Father,” he told John Paul. “I am a diocesan bishop; I have to be in my diocese.”

He ultimately agreed to come to Rome in 1982.

In our interview, he spoke of fostering a dialogue between theologians and his office, but theologians who lost their jobs or were silenced by him did not experience it that way. He was upset by the insulting language of attacks on his office, even if he could laugh at the situation.

(I should have remembered this years later before foolishly referring to the “inquisitional” procedures of his congregation in an editorial in America.)

What is most striking about the interview today was his admission, “I do not have charism about structural problems.”

In other words, Ratzinger was at heart a scholar not a manager, but he would become head of a billion-member organization with a hierarchical structure and a complex bureaucracy in Rome.

In 1998, after my book was published, I became editor-in-chief of America, a magazine first published by Jesuits in 1909. My goal was to make it “A magazine for thinking Catholics and those who want to know what Catholics are thinking.”

Although almost always careful in editorials to stick to the Vatican line, I thought I could publish alternative views in the opinion section of the magazine if I insisted that these articles did not necessarily represent the views of the magazine.

We were, after all, a journal of opinion.

During my seven years as editor, the CDF published important documents on which I asked relevant scholars to comment. They usually praised the parts they liked, and criticized those they did not.

I was always happy to publish critical responses to these articles.

I also published articles by many bishops and cardinals, including then Archbishop Raymond Burke, whom I invited to explain why the church should deny Communion to pro-choice Catholic politicians. I asked Chicago Cardinal Francis George, a prominent conservative, a half dozen times to write something for us, but he always refused.

A high point of the magazine as a forum for dialogue was a submission by Cardinal Walter Kasper, the head of the Vatican ecumenical office, criticizing the ecclesiology of Cardinal Ratzinger.

As the article was going to the printers, I sent a copy to Ratzinger, inviting his response.

At first, he declined, but later changed his mind and sent a response in German, which we had translated and published.

We were delighted to have two prominent cardinals debating an important issue in the pages of America, but later I learned that Cardinal George complained about the exchange and asked the Vatican Secretary of State to tell the cardinals not to debate in America because it scandalises the faithful.

Despite my attempts to be fair, it became apparent that neither John Paul nor Cardinal Ratzinger wanted a journal of opinion unless it reflected their opinions.

After two and a half years as editor, I heard from the Jesuit superior general, Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, that the Vatican was unhappy with an article on AIDS and condoms written by Jesuit theologian James Keenan and Jesuit physician Jon Fuller.

I would have been happy to publish a rebuttal from anyone in the Vatican, but I never received anything directly from the congregation.

The congregation always communicated with me through my Jesuit superiors.

In June 2001, I was told that the congregation found “Father Reese’s way of criticising the Holy See, and particularly the congregation, aggressive and offensive.”

In particular, they took issue with an editorial we ran on due process in the church (April 9, 2001).

We were accused of being anti-hierarchical.

At the end of February 2002, Father Kolvenbach said that CDF had decided to impose a commission of ecclesiastical censors on America “at the request of American bishops and the nuncio.”

The censors would be three American bishops.

Not only was this a bad idea, it was totally impractical, since we published weekly.

In April, I received a list of items published in America that the congregation did not like.

They included a book review by Jesuit historian John O’Malley of “Papal Sins,” the article by Keenan and Fuller, an article on homosexual priests by Jesuit James Martin and articles on the CDF document, “Dominus Iesus,” by Francis X. Clooney, Michael A. Fahey, Peter Chirico, and Francis A. Sullivan.

Ratzinger seemed to have a thin skin when it came to documents coming out of his congregation.

Only two editorials were mentioned — one on “Dominus Iesus” (Oct. 28, 2000) and the other on “the abortion pill,” RU-486 (Oct. 14, 2000). We condemned the abortion drug but hinted that it might be time to rethink the church’s teaching on birth control as a way of reducing the number of abortions.

Interestingly, America’s extensive and forceful coverage of the sex abuse crisis was never mentioned by the congregation, though I knew that some American bishops did not like it.

Ratzinger, although not perfect, was better than anyone else in Rome on the topic.

No one could tell me which U.S. bishops had requested the censorship board.

I knew it had never come up at a meeting of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Nor was it discussed at the USCCB’s administrative committee, according to my sources, among them Archbishop Thomas Kelly, who was on the committee during this time.

When I asked Bishop Donald Trautman, chair of the USCCB Committee on Doctrine, he grew furious that a censorship board was set up without consulting his committee. He planned to object vigorously.

Nor was American Archbishop John Foley, head of one of the communications offices in the Vatican, consulted.

He said that, if he were asked, he would have said it was a bad idea. He jokingly referred to himself as the “left wing of the Roman curia.”

I asked for help from Archbishops Kelly, John Quinn and Daniel Pilarczyk, but they all said that they were not trusted by Rome, so their support would do no good.

Quinn and Pilarczyk had been presidents of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and Kelly had been conference general secretary and on the staff of the papal nunciature in Washington.

I approached Jesuit Cardinal Avery Dulles, who thought a censorship board was a terrible idea. He promised to put in a good word for me with Ratzinger.

“You publish me,” the very orthodox cardinal said.

Sometime before the end of July 2003, Kolvenbach met with Ratzinger and was able to talk him out of imposing a censorship board.

Kolvenbach warned me that the congregation would be watching to see how America responded to CDF’s upcoming document on gay marriage.

I asked Associate Editor James Martin, who had written extensively on gays in the church, not to say anything about the document. I wanted to protect him and the magazine.

He agreed.

Our first article on the subject was on June 7, 2004, by Monsignor Robert Sokolowski, a philosopher at the Catholic University of America, who was strongly opposed to gay sex and gay marriage.

I had to talk him into dropping a paragraph comparing gay sex to sex with animals.

His article, not surprisingly, elicited strong responses, one of which came from Stephen Pope, professor of theology at Boston College.

Even though I got Pope to tone the article down a notch, and even though I allowed Sokolowski to respond to Pope in the same issue, I knew as it went to the printers that this could be the final nail in my coffin.

Although I had never opined or editorialized on the topic, it was clear that merely allowing a discussion of some issues in America was more than Ratzinger would tolerate.

Almost immediately after the publication of the December 6, 2004, issue, my American superior heard complaints from the papal nuncio in Washington. He also complained about an article on politicians, abortion and Communion by U.S. Representative Dave Obey, who had been denied Communion by Burke.

There was acknowledgement that we published articles on both sides of the “wafer war.”

As 2005 progressed, the world focused on the sickness and death of John Paul and the conclave that elected Ratzinger Pope Benedict XVI. During this time, I was busy working with the media, explaining and commenting on what was happening.

Before the conclave, at an off-the-record dinner with some journalists in Rome, I was asked, “What would be your reaction if Ratzinger was elected pope?”

I responded, “How would you feel if Rupert Murdoch took over your newspaper?”

On the day of Ratzinger’s election, I had already promised to appear on the PBS Newshour.

On the program, I blandly opined that some people will like the results, some won’t.

After that, my response to press inquiries was “no comment,” because I believed that his election was a disaster but, as Jesuit, I could not say so.

On April 19, 2005, as I heard the announcement of Ratzinger’s election in St Peter’s Square, I knew my tenure as editor of America was over.

For the good of the magazine and the good of the Jesuits, I had to go.

In addition, after seven years of looking over my shoulder, I had had enough.

I stopped giving interviews and left Rome.

When I got back to New York, the other Jesuits at the magazine would not let me resign.

A few days later, I met with my superior, the president of the Jesuit Conference, and learned that my time as editor was over.

Only then did I learn that back in March, Ratzinger had told the Jesuit superior general that I had to go.

For various reasons they had not gotten around to telling me.

So I resigned.

My Jesuit superiors had always been very supportive of my work, but I knew that ultimately, they could not protect me unless I was willing to compromise my values as an editor.

They had not been able to protect numerous Jesuit theologians who had been disciplined by CDF.

When the news hit the press, I was portrayed as Benedict’s first victim; the truth was, I was the last victim of Cardinal Ratzinger. Because I was so well known by the media, who had frequently used me as a source, the coverage was extensive and negative toward the new pope.

The coverage was so bad that the Vatican stepped back from the planned removal of the Jesuit editor of the German journal, “Stimmen der Zeit” (“Voices of the times”). They let him serve out his term as editor.

If I were a unique case, my story would be interesting but not important in judging the legacy of Joseph Ratzinger.

Sadly, mine is only one of hundreds of examples of the repression of free inquiry by reporters and theologians during the papacies of John Paul and Benedict.

A few months before my resignation, Jacques Dupuis, a distinguished theologian who had been disciplined by Ratzinger, told us the story of his own meeting.

After the congregation had condemned one of his books, the elderly (and ill) theologian prepared a 200-page response.

When he met with Ratzinger and the CDF, he told the editors of America, they surprised him by asking him for his response.

When he pointed to the document on the table before them, which had taken him months of work, they scoffed, “You don’t think we’re going to read that, do you?” Dupuis died not long after our meeting.

Whether I was right or wrong in my views is irrelevant.

What matters is that after the Second Vatican Council open discussion was suppressed by Ratzinger under the papacy of John Paul.

If you did not agree with the Vatican, you were silenced.

Yet, without open conversation, theology cannot develop, and reforms cannot be made.

Without open debate, the church cannot find ways of preaching the gospel in ways understandable to people of the 21st Century.

The papacy of Pope Francis has reopened the windows of the church to allow the fresh breeze of the Spirit. Conversation and debate is possible again, even to disagreeing with the pope.

Unlike his predecessors, Francis does not silence his critics.

Change will not happen quickly enough for many in the church, but allowing the conversation to flourish is essential to preparing for reform.

- Thomas Reese SJ is a senior analyst at Religion News Service, and a former columnist at National Catholic Reporter, and a former editor-in-chief of the weekly Catholic magazine America. First published in RNS. Republished with permission.