Thomas Aquinas would have agreed with a comment on this website that he was as vulnerable to error as anyone else and should never be taken as “the truth”. He has read widely and deeply: Aristotle’s influence is evident throughout the Summa Theologica, as is that of St Augustine. Other philosophical influences include the pagan (Plato and the Stoics, Dionysius and Boethius), the Muslim (Ibn Rushd,aka Averroes, and Ibn Sina, aka Avicenna); and the Jewish (Maimonides). But Aquinas argues that theological first principles derive from scripture, which is the ultimate authority for Christian doctrine. All other thinkers, however great, must be measured against the biblical authors.

This does not make Aquinas a biblical literalist. He argues that the Bible is written in metaphors that render the divine mystery meaningful for finite human minds. We depend on material objects for our knowledge, and therefore we can only speak of God as if God, too, were part of the material world. Biblical language is multilayered, opening itself to mystery the more one allows its meanings to unfold. Aquinas says of scripture that “the manner of its speech transcends every science, because in one and the same sentence, while it describes a fact, it reveals a mystery” (ST I.1.10). Anyone who has ever thrilled to poetry understands this. Profound truths speak to us through ordinary metaphors when we take time to listen and reflect. Indeed, Aquinas insists that we should avoid exalted imagery when we speak about God, in case we are deceived into taking our language too literally. Read more

Sources

- Tina Beattie in The Guardian

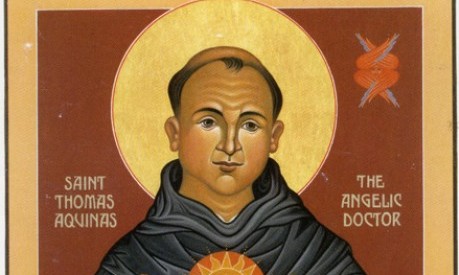

- Image: London Lay Dominicans

- See also: Thomas Aquinas, part 2: the mind as soul and Thomas Aquinas, part 1: rediscovering a father of modernity

- Tina Beattie is Professor of Catholic Studies at Roehampton University, London, and a frequent contributor to the Catholic weekly, The Tablet and the online journal, Open Democracy

News category: Features.