One of the buzz-phrases of Catholic theology – cited in virtually every document from the Vatican – is that the liturgy, and especially the Eucharist, is ‘the source and summit’ of the Christian life.

The origins of the phrase are complex, but it enters mainstream Catholic discourse with the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy in this sentence:

Indeed, the liturgy is the summit (culmen) towards which the activity of the Church is directed; it is also the fountain (fons) from which all her power flows (n.10).

That was in 1963 and it is now a piece of stock wisdom.

Like all such snippets of wisdom it is more often parroted than thought about. For most of the people who quote it, it is just another way of saying that ‘the Mass is what is most important’ or a striking metaphor to say that prayer is what must come first in the life of a Christian. It is – when read through the so-called ‘hermeneutic of continuity’– simply a new formulation of the tag: ‘it’s the Mass that matters.’

But that reading fails to note that it is also far more that a restatement: it is a different theological vision that is based on a dynamic understanding of the life of the Church as the living, moving witness to the gospel in the world.

Two-way street or perhaps a round-about

The image implies of a series of stages that lead up to the summit. Liturgy does not simple happen: it must be prepared for by a whole range of activities that fall in every area of our lives. Likewise, liturgy is not something that after it has happened, we leave to get on with the rest of life. There is no simple division of Sunday / Monday; the religion bit in the church / the rest of life outside. There is no neat border separating the sacred and the profane.

If liturgy is real, it expresses what is happening in our lives before God in worship.

If liturgy is real, it expresses what is happening before God in worship in our lives.

The Eucharist – the highest expression of our worship – has to be seen not as an island, but a point along a road: there is a road of thankfulness and reconciliation leading up to it, and a road of generosity and thankfulness leading on-wards in our lives.

Perhaps the image of a roundabout is better as a dynamic image of how liturgy relates to the rest of our lives.

Liturgy is a roundabout

All the roads of our lives – relationships, family, work, social engagement, politics, sport, entertainment … … … should flow towards it as we express our lives in the presence of God. From that expression, the roads flow outwards into those same areas of our lives, but, hopefully with a new vision and a new energy to bring them towards their finality in God.

It is the replacement of a static image of worship with this dynamic one, embracing the whole of life, that is the real achievement of the Second Vatican Council – and the reason why, in the face of pushback, Pope Francis has said that there is no place of those who reject Vatican II.

When the Pope met the Grand Imam

But if the Eucharist is the summit, what do some of the lower slopes look like?

Well, we have a good view of one of those slopes in a small event that took place when the Pope met the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayyeb, and co-wrote the Document on Human Fraternity, which they presented to the world in Abu Dhabi on Feb. 4, 2019.

At an earlier meeting in the Vatican, on 6 November 2017, the two had lunch. At the outset the Pope asked the Grand Iman to pray for humanity and peace. Then the Pope took up a piece of bread, cut it in half, gave the Grand Iman one half, and both ate their share. It was a real sharing of one piece of bread, and a message to all of us about sharing and reconciliation.

Reconciliation in shared food at table with others is at the heart of our human experience.

Reconciliation in shared food at table with others and with God is at the heart of our eucharistic experience.

One does not get to the summit without traversing the lower slopes!

President-elect Biden at the Foodbank

If the Eucharist is the fountain of Christian life, then what should blossom with the water flowing from that fountain?

On 18 January, just before his inauguration, Joe Biden went and volunteered at a food bank.

He had, no doubt, much office work to do and many to see – so it was a symbolic gesture analogous to that of the pope with the grand iman. But why use his time in this way?

If we have shared with one another in the Lord’s banquet, then we must also be conscious of the needy. The Lord is generous with us, we express that in our generosity with others. Biden’s action put sharing our food – a fundamental and real image of all our resources – with the poor as close to the centre of his presidency.

Service involves sharing.

Riches involve service.

Taking a turn at working in a foodbank is, within the Christian vision, not simply just a generous human action, it is a statement that all our riches are a gift. And God’s gifts must be shared if we are to bear fruit. Biden’s action is full of eucharistic significance.

At a Eucharist we become recipients of God’s gifts.

At a Foodbank we become distributors of God’s gifts.

What we discover at a foodbank can enrich our liturgy.

What we discover at liturgy can stock and staff a foodbank.

Liturgy is the roundabout of our humanity.

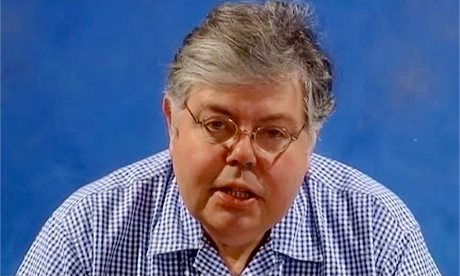

- Thomas O’Loughlin is a priest of the Catholic Diocese of Arundel and Brighton, emeritus professor of historical theology at the University of Nottingham (UK) and director of the Centre of Applied Theology, UK. His latest award-winning book is Eating Together, Becoming One: Taking Up Pope Francis’s Call to Theologians (Liturgical Press, 2019).