In late April, during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, two ethnic Uyghur women sat behind a tiny mesh grate, underneath a surveillance camera, inside the compound of what had long been the city’s largest place of worship.

Reuters could not establish if the place was currently functioning as a mosque.

Within minutes of reporters arriving, four men in plainclothes showed up and took up positions around the site, locking gates to nearby residential buildings.

The men told the reporters it was illegal to take photos and to leave.

“There’s no mosque here … there has never been a mosque at this site,” said one of the men in response to a question from Reuters if there was a mosque inside. He declined to identify himself.

Minarets on the building’s four corners, visible in publicly available satellite images in 2019, have gone.

A large blue metal box stood where the mosque’s central dome had once been. It was not clear if it was a place of worship at the time the satellite images were taken.

In recent months, China has stepped up a campaign on state media and with government-arranged tours to counter the criticism of researchers, rights groups and former Xinjiang residents who say thousands of mosques have been targeted in a crackdown on the region’s mostly Muslim Uyghur people.

Officials from Xinjiang and Beijing told reporters in Beijing that no religious sites had been forcibly destroyed or restricted and invited them to visit and report.

“Instead, we have taken a series of measures to protect them,” Elijan Anayat, a spokesman for the Xinjiang government, said of mosques late last year.

Foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said on Wednesday some mosques had been demolished, while others had been upgraded and expanded as part of rural revitalization but Muslims could practice their religion openly at home and in mosques.

Asked about restrictions authorities put on journalists visiting the area, Hua said reporters had to try harder to “win the trust of the Chinese people” and report objectively.

Reuters visited more than two dozen mosques across seven counties in southwest and central Xinjiang on a 12-day visit during Ramadan, which ended on Thursday.

There is a contrast between Beijing’s campaign to protect mosques and religious freedom and the reality on the ground. Most of the mosques that Reuters visited had been partially or completely demolished.

China has repeatedly said that Xinjiang faces a serious threat from separatists and religious extremists who plot attacks and stir up tension between Uyghurs who call the region home and the ethnic Han, China’s largest ethnic group.

A mass crackdown that includes a campaign of restrictions on religious practice and what rights groups describe as the forced political indoctrination of more than a million Uyghurs and other Muslims began in earnest in 2017.

China initially denied detaining people in detention camps, but has since said they are vocational training centres and that the people have “graduated” from them.

The government says there are more than 20,000 mosques in Xinjiang but no detailed data on their status is available.

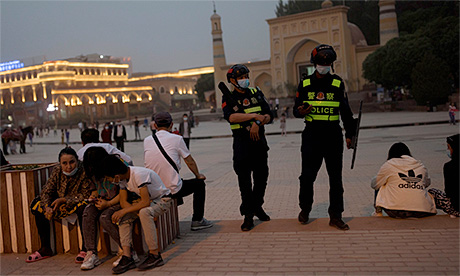

Some functioning mosques have signs saying congregants must register while citizens from outside the area, foreigners and anyone under the age of 18 are banned from going in.

Functioning mosques feature surveillance cameras and include Chinese flags and propaganda displays declaring loyalty to the ruling Communist Party.

Visiting reporters were almost always followed by plainclothes personnel and warned not to take photographs.

A Han woman, who said she had moved to the city of Hotan six years ago from central China, said Muslims who wanted to pray could do so at home.

“There are no Muslims like that here anymore,” the woman said, referring to those who used to pray at the mosque. She added: “Life in Xinjiang is beautiful.” Continue reading

Additional readingNews category: Analysis and Comment.