You are lying asleep in your bed in the home you own. It should be the most comfortable place but, before the sun is up, police are knocking on your door and you will have to convince them you deserve to stay.

They’re shining a torch into your face, holding back a German shepherd “frothing at the mouth”.

It’s 1974 and this is a dawn raid. If you can’t prove who you are, you will likely be locked up and eventually deported.

New Zealand has achieved cult status as a progressive haven at the bottom of the world, but talk to Pacific Islander people and many will tell you about the 1970s and the “state-sanctioned racism” that ripped them from their homes.

The immense shame of the dawn raids lingers — on both sides of politics and on the Pacific families that woke to that knock at the door.

Today, the New Zealand government will apologise but, for one group of social justice revolutionaries, saying sorry is just the beginning.

The Polynesian Panthers

Fifty years ago, a group of teenagers came together in Auckland for the inaugural meeting of the Polynesian Panthers.

The date was June 16, 1971 and the first generation of New Zealand-born Pacific people had decided to organise.

They were reading Bobby Seale, listening to Bob Dylan’s “songs of protest” and watching as the Black Panthers forced the United States to reckon with its racist history.

Melani Anae was at that first meeting of the Polynesian Panthers. To become a member, she had to read Seize the Time — the story of the Black Panther Party.

“When I read that book, I couldn’t get over how much it mirrored what we as Pacific communities were living through,” she said.

“Problems with housing, problems with education and problems with adjusting to a new life. And we really resonated with that and so we were totally in solidarity with the Black Panthers.”

Now an associate professor of pacific studies at the University of Auckland, Dr Anae said she didn’t realise it at the time but becoming a Panther as a teenager would define her life.

“The Panthers were the first of the first. The first New Zealand-born Pacific generation,” she said.

“We had no role models. Our parents who came to New Zealand were very respectful of authority. They wanted to be good citizens, but us New Zealand-borns knew something was wrong.

“So, as 17-year-olds we took it upon ourselves to form the Panthers to fight that racial injustice.”

Maori people are indigenous to New Zealand, while people from island nations such as Samoa, Tonga and Fiji immigrated to the country.

Both Maori and Pacific people face disadvantages and discrimination, but the Polynesian Panthers stand for the Pacific community.

Our hope is very person who goes to school, learns these stories and perhaps in the learning — even just the hearing of these stories — they might understand diversity. They might understand how better to relate to difference — to cultural difference.

After World War II, the New Zealand government called for people from the Pacific Islands to come and fill the labour shortages, to do “the jobs ordinary New Zealanders didn’t want to do”.

“They invited us, so we came in droves,” Dr Anae said.

“My parents came because they wanted a better life, but when the economic recession hit in the early 1970s … the immigration policy suddenly changed and they didn’t want us anymore.”

Dr Anae said Pacific people then became the “scapegoats for successive governments, both Labor and National”.

The political messages focussed “on the immigration of these brown people from the islands and that they were taking ordinary New Zealanders’ jobs, and that they were criminals and rapists and murderers”, she said.

The government of the day was cracking down on “overstayers” — people who were living in New Zealand illegally after their visas or work permits had expired.

But immigration officials were only targeting overstayers from Pacific island nations, when the bulk of people who were living in the country illegally were from Europe and North America. And the police enforcing the immigration warrants were terrorising Pacific communities.

The Panthers fought back. At a higher level, they fought against the narrative the government and media of the time had spun about them. And at a grassroots level, they fought to genuinely improve the lives of those in their community.

“The crucible years, I believe, were 1971 to 1974, was when the Panthers were the strongest and fiercest, in terms of our membership, which had reached 500 people. That’s when we put our community survival programs in place,” Dr Anae said.

“We had homework centres, we had food co-ops, we had the PIG patrol — the Police Investigation Group — which stopped the police from harassing our communities … just for being who we were.”

The Panthers assigned portfolios to their members.

There were ministers for finance, cultural affairs and information. There was also a Tenants Aide Brigade. The Panthers’ platform has always been “educate to liberate” and as Pacific people became targets for random police checks, the group made sure everyone knew their rights.

One of the lasting legacies of the 1970s-era Panthers is the group’s contribution to legal aid in New Zealand.

A prominent lawyer helped produce the Polynesian Panthers’ legal aid booklet, which was widely distributed among Auckland’s Pacific community.

It was a revolution. For people who had been targeted by police to learn not just that they had legal rights, but specifically what they were, was powerful.

The lawyer who penned the legal advice was David Lange. It would be another decade, but Lange became the 32nd prime minister of New Zealand.

People soon learned that if a police officer didn’t have his badge or hat on, he was not in full uniform and technically he could not make an arrest.

The “PIG Patrol” would be there to watch police, keeping an eye on their tactics — and whether or not their uniform met standards — as they tried to pull young Pacific Islander people off the street.

The Panthers were getting smarter and stronger. They were making a difference in their communities, but they were agitating too. They came together to push back against racist policies and sometimes that got physical.

The Polynesian Panthers had a military wing. There were clashes with police and landlords, and a determination to be a force on the ground. Members of this faction were prepared to break the law and several of them did, serving time for rioting, illegal assembly and fighting police.

Founding member Will Ilolahia has been quoted as saying: “The thing about the Panther … it never attacks.

“But if it’s attacked itself and it’s caught in a situation that calls for self-defence, it will respond.”

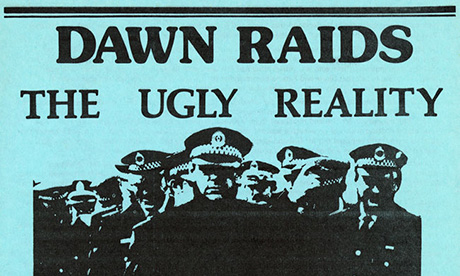

The dawn raids

The most insidious of actions by the police, Dr Anae says, were the raids the New Zealand government will now apologise for.

“In 1974 to 1976 there was the horrendous state-sanctioned racism called the dawn raids,” she said.

“The dawn raids targeted Pacific families. The theory was these families were likely to have overstayed visas and so police targeted them in the street, knocked on their doors in the early hours of the morning.”

When New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the apology, Minister for Pacific Peoples Aupito Sio stood beside her at the press conference.

“We were dawn raided,” he said.

“The memories are … of my father being helpless. We bought the home about two years prior to that and to have somebody knocking at the door in the early hours of the morning, with a flashlight in your face, disrespecting the owner of the home, with an Alsatian dog frothing at the mouth … wanting to come in.

“It’s quite traumatising.”

For some Pacific families, their loved ones were picked up off the street and sent away without notice. For others, they were raided in the night and never told another soul.

It’s only now that the government has announced it will apologise for the practice that the community has really started to open up.

Christine Nurminen was born in 1975 to Tongan parents who had come to Auckland to work.

Her childhood memories are underwritten by the fear her family lived through every day. She remembers being confused about her parents’ anxiety and why they were always worried about dogs.

“We would be like ‘why are we driving the long way around? Or why are these people on the property? Or why is everyone so anxious about the dogs?'” Ms Nurminen said.

“There was this constant language around the dogs. ‘Don’t let the girls play outside with the dogs, we’ve got to be worried about the dogs’ but I knew we didn’t own dogs and I was petrified.”

Ms Nurminen said it was only as an adult that she came to learn about the dawn raids and how police used dogs to find anyone who might be hiding in the property.

“Every Tongan person I know always talks about the dogs,” she said.

Her family had a strategy.

“All the women lived in one part of the house and all the men lived in one part of the house and they’d just take turns watching the door and watching for police,” Ms Nurminen said.

“The thinking was, if we’re going to be raided, at least the women feel safe together and there’s no random male [police officer] coming through where they’re sleeping.”

Polynesian Panther member and Samoan New Zealander Alec Toleafoa remembers being targeted on the street — the “blanket random checking on all people who were brown”.

“We were required to carry proof we were entitled to be here lawfully,” he said.

“In my case, and my siblings’, we’re only 13, 14, 15 at that time. We’re all New Zealand-born, we’ve never travelled anywhere, why would we have a passport? I would be hoping like hell I would not be stopped and questioned because I had no evidence I was here legally.

“So when we saw police we knew there was a high likelihood we would not be going home that day.”

Mr Toleafoa said it was the “brutal arm” of the police that pulled him towards the Panthers.

“[We would be] just walking along the street and then a patrol car pulls up, asks us a certain set of questions,” he said.

“As soon as we reply we find ourselves in restraints and thrown in the car, taken away from our neighbourhood and given the beat down and then dropped back as if nothing had happened.

“That happened to me.” Continue reading

- John Miller has documented New Zealand’s social justice movements for 50 years

News category: Analysis and Comment.