Sexual abuse is rooted in abuse of power, which is very often the first step.

While abuse of power can take many forms, many abusers rely on the excessive and, let’s say it, clericalist use of secrecy.

For decades many Church bodies, including the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, have repeatedly called for removing the pontifical secret.

On December 17, 2019, Pope Francis finally lifted it for cases of sexual violence and abuse of minors committed by members of the clergy.

Nevertheless, this is just one step.

A culture of secrecy still exists in the Church, for reasons not always justified and or even healthy.

This culture continues to contribute to authoritarianism, clericalism and patriarchalism – all attitudes deeply disrespectful of equality among the baptized.

We can cite three examples.

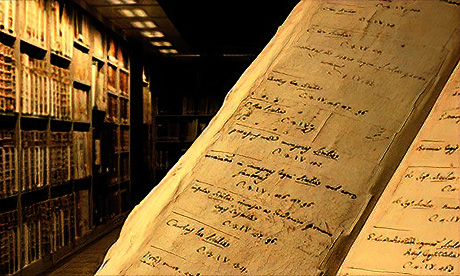

Crimen sollicitationis, a text that remained secret for more than a century

We know today, without yet knowing all the twists and turns, the journey of the text Crimen sollicitationis, aimed at setting up procedures to respond to the case where a cleric solicits sexual favours in the context of confession.

The issue was explosive. The Church first addressed it in 1741 and included it in the 1917 Code of Canon Law.

But the text explaining the procedure to be followed in case of the “crime of solicitation”, which gave its name to this document, was published for the first time in 1922.

Yet it remained secret. We only learned of its existence in 1962!

This document contained practical procedures to follow when dealing with an abusive cleric. But it was never officially published. It was sent only to a few episcopal conferences.

Which conferences and why?

Is it enough to invoke a certain idea of “harm done to the Church” to justify this secrecy?

Was it not, on the contrary, a question of doing “good” to the Church at a time when it had to face up to the evidence of reality?

Crimen sollicitationis remained in force until 2001.

The lack of transparency surrounding the condemnation of contraception

The second example has been investigated many times.

At the time of Vatican Council II, Pope Paul VI reserved the question of birth control for himself.

He appointed a “Papal Commission for the Study of Problems of the Family, Population, and Birth Rate”. Its work was to remain secret.

But in June 1964 the pope revealed the commission’s existence.

Catholic public opinion was overwhelmingly positive.

Successive leaks have revealed that experts known for their conservatism had rallied around the idea of new directives, and thus Paul VI felt compelled to enlarge the commission several times.

But in the end, the majority of the commission’s members agreed that “contraceptive intervention”, i.e. the pill, was permissible!

But the text was not published, nor were the negotiations that took place from October 1966 (when the commission submitted its report to Pope Paul) until the July 1968 publication of Humanae vitae.

That controversial encyclical, of course, did not endorse the commission’s report. Instead, it condemned the use of artificial contraception.

As Martine Sevegrand reminds us, “the encyclical is the revenge of the men of the curia… disavowing practically all the experts and a strong majority of bishops”.

Two conclusions can be drawn from this.

First, according to the words of Christ, “nothing is hidden that will not be revealed, nothing is secret that will not be known” (Luke 12,2), and at the moment of revelation, the scandal is twice as bad.

And then, was Humanae vitae never welcomed because the People of God (and even the fathers of the council) were not ultimately involved in this reflection that took place in the shadows?

Female diaconate, a report never published

A third example is both a protest and a demand for today.

It concerns the commission for the female diaconate set up by Pope Francis on April 9, 2020.

Following the 2003 work of the International Theological Commission, Francis appointed a commission in 2016 in response to numerous requests, including that of the International Union of Superiors General (UISG).

It finally submitted its report in May 2019.

But this document, which was supposed to provide arguments, was never published.

Why?

What were they afraid to disclose?

The pope himself was not satisfied and appointed a new commission.

But what will come of it? Will this commission finally make its arguments public?

The question of the diaconate, like that of birth control, and like many other issues, cannot be confined to the secret archives of the Roman Curia.

These texts are not secret, since they must be rooted in the Word of God and the practices of the early Church.

All their arguments must absolutely be published and made available to the People of God. If they are not, the people cannot accept them.

Wanting to maintain the secrecy of texts that should not be kept secret is to further contribute to the logic of collapse highlighted by the recently published report on the sexual abuse in the French Church.

- Marie-Jo Thiel is a physician who teaches ethics in the theology department at the University of Strasbourg (France). She is an award-winning author of numerous books and essays.

- First published in La-Croix International. Republished with permission.

News category: Analysis and Comment.