It has become somewhat of a cliche for media reports and climate scientists to actively link modern extreme weather events in New Zealand with climate change, but an accurate answer requires more or less complete knowledge of our past recorded climate.

A new study by journalist and author Ian Wishart into historic extreme weather events has found however that the vast majority of extreme weather events from our past appear to be missing from NIWA’s Historical Weather Events database for researchers and journalists.

Specifically, of 24 major climate events that took place in a 22 year period leading up to 1890, only four have been loaded into the NIWA research database, meaning 83% were missing.

The missing appear to include many storms bigger than Cyclone Gabrielle.

Climate of fear

A NIWA database claiming to document major historic climate events for journalists and researchers has no records of most of New Zealand’s biggest historic storms, throwing claims that “extreme climate events” are becoming more common into serious doubt.

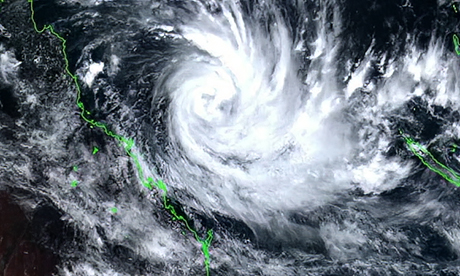

As New Zealand mops up in the wake of its most devastating cyclone in 60 years, questions are naturally being asked by insurers, the public and the politico-media establishment about whether “extreme climate” is now already here, as claimed by the Greens and climate scientists.

National’s Maureen Pugh found herself in hot water after questionning the “evidence” linking Cyclone Gabrielle to climate change.

In a Masterclass of Media-Gotcha! 101, Newshub’s political editor Jenna Lynch quickly lined up Greens co-leader James Shaw, assorted climate scientists and lobbyists and even National’s leader Chris Luxon to scornfully force Pugh into a “climate ‘Come to Jesus’ moment” where she publically repented of her sin in daring to question the daily media assurances that humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions are a major contributor to New Zealand’s summer soaking.

The media and politicians rely on briefings and resources from NIWA, including its searchable Historic Weather Events Catalogue that allows quick access to data on “major” storms in the past. Want to know about big storms in Esk Valley? Just punch it in.

Except, and this is the elephant in the climate change room, most of New Zealand’s biggest storms between 1868 and 1890 (a random period selected to examine) are not actually in there. And if most of the major events from the 1800s are not there, what about the 1900s?

Why is this critically important?

It’s fundamental to “trusting the science” because public and political faith requires science to maintain complete and trustworthy records.

A failure to do a proper data search of historical storm records and upload them means the public, politicians, insurers, banks and even the news media are recieving flawed information that is skewed to accurately record every modern climate event while missing more than 80% of major historical events.

That creates an overwhelming impression that the weather is getting more extreme – an impression that you will shortly see may not only be wrong, but the reverse: in New Zealand, at least, there’s evidence that we suffered more so-called 1-in-100 year storms/floods in the 1800s (when CO2 was only around 285ppm) than now (413ppm).

Let that sink in for a moment: there’s evidence of a higher frequency of big storms more than a century ago when the planet was colder, with much lower CO2 levels.

If that turns out to be correct, where does that leave the “climate change means more extreme weather” narrative pushed in the nighly news?

To figure this out, we first have to find an agreed measurement for storm intensity.

NIWA’s Ben Noll this week published new analysis of our three biggest storms in recent times – Cyclone Giselle in 1968 (the ‘Wahine’ storm), Cyclone Bola in 1988 and now Cyclone Gabrielle.

Noll and colleagues ran data from the three storms through a NOAA reanalysis and found that Gabrielle had a deeper “low”, at 963 hectopascals (hPa) than Giselle on 968 or Bola at 982 hPa.

Traditionally, cyclones and hurricanes have been measured on wind strength from Categories 1 to 5, but a 2022 study makes the case that the atmospheric depression – or Minimum Sea Level Pressure (MSLP) caused by a storm may be a more accurate measure of its destructive ability because it is a better predictor of rainfall, storm surge and windspeed than measuring windspeed alone.

The reason is that cyclones are more than just wind or rain – their low atmospheric pressure (weight) at sea level in the centre of the storm means the sea level can rise up to 14 metres above high tide.

That means if you were standing on a beach at high tide mark, a hurricane could make the tide rise a further 12 or so metres above your head…enough to flood a four storey building.

Thankfully, that level of surge has been recorded only once, with Cyclone Mahina in Australia in 1899. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 caused an eight metre storm surge that drowned New Orleans.

Most storm surge in NZ is much lower, between one and three metres, because the cyclones have weakened from their peak.

Cyclones are like a giant robotic vacuum cleaner sucking heat out of the oceans through a column at the Eye.

The more energy they can find and spew up the funnel in the middle, the faster and more violent are the winds on the fringes as cold air rushes in to replace the air being sucked up the heat column.

It’s this suck up the middle that also causes sea level rise via storm surge in that area.

This storm surge effect is the real reason urban planners are scared about climate change in the short to medium term.

A baseline sea level rise of 30cm or even a metre of tidal rise on a beach over the next century won’t break the bank in most cases, but if it’s coupled with two or three metres of storm surge every couple of years it could make shopping along the boulevard a tad unpleasant.

Given that most shoreline streets are only a couple of metres above high tide mark, the difference between three metres and 3.3 or even four metres of surge may ultimately be academic.

When the barometer dives, it means the weight of the air on the sea reduces and sea level rises for the duration.

The Ben Noll analysis pegged Gabrielle, with an MSLP of 963 hPa (the Met Service says it was 966.6), as one of New Zealand’s biggest ever storms, outranking hall-of-famers like 1988’s Bola (982 hPa) and Giselle (968 hPa) twenty years earlier than Bola.

Let me say from the start that there’s debate in scientific circles about just how much global warming has played a part in fuelling its intensity.

NIWA has pitched that it could have increased moisture retention in the cyclone – and therefore how much rain would come back down, by 5-10%.

However, other scientists have pointed out that the Tongan eruption last year punched 146 million tonnes of water vapour into the atmosphere, which not only will fuel warming because water vapour is a powerful greenhouse gas – but what goes up generally will come down, and cyclones and weather bombs are one way for Earth to rebalance.

So it isn’t really possible for anyone to say that Gabrielle was fuelled by car exhaust fumes.

But how did Gabrielle really compare to some of the big storms that ravaged NZ after British settlement? Continue reading

Executive Summary

- Most of New Zealand’s biggest historic storms and cyclones are missing from NIWA’s Historic Weather Events Database (DATA GAPS>80%)

- The missing data is crucial for providing answers about whether extreme climate events are becoming more common (FREQUENCY)

- The missing data is crucial for journalists and researchers trying to compare the magnitude of modern climate events with those of the past (INTENSITY)

- Between 1868 and 1890 NZ was being hit yearly on average by storms similar to or more powerful than Cyclone Bola

- Five storms geographically bigger and with deeper barometric lows than Cyclone Gabrielle struck New Zealand between 1868 and 1890, revealing that what we call a 1-in-250yr event was actually closer to a 1-in-4yr event back then

- The late 1800s was a much colder, low-carbon climate, raising fundamental questions about how extreme weather events play out in the real world vs computer modelling. Continue reading

Source

- Ian Wishart – www.investigatemagazine.co.nz Reproduced with permission.

- Download the full report.

News category: Analysis and Comment.