When faced with infertility, Amanda and Jeff Walker had a baby through in vitro fertilisation but were left with extra embryos — and questions.

Embryo adoption

Tori and Sam Earle “adopted” an embryo frozen 20 years earlier by another couple. Matthew Eppinette and his wife chose to forgo IVF out of ethical concerns and have no children of their own.

All are guided by a strong Christian faith and believe life begins at or around conception.

And all have wrestled with the same weighty questions: How do you build a family in a way that conforms with your beliefs? Is IVF an ethical option, especially if it creates more embryos than a couple can use?

“We live in a world that tries to be black and white on the subject,” Tori Earle said. “It’s not a black-and-white issue.”

Faith v. science

The dilemma reflects the age-old friction between faith and science at the heart of the recent IVF controversy in Alabama, where the state Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos have the legal status of children.

The ruling — which decided a lawsuit about embryos that were accidentally destroyed — caused large clinics to pause IVF services, sparking a backlash.

State leaders devised a temporary solution that shielded clinics from liability but didn’t address the legal status of embryos created in IVF labs. Concerns about IVF’s future prompted U.S. senators from both parties to propose bills aiming to protect IVF nationwide.

Laurie Zoloth, a professor of religion and ethics at the University of Chicago, said arguments about this modern medical procedure touch on two ideas fundamental to the founding of American democracy: freedom of religion and who counts as a full person.

The religious question

“People have different ideas of what counts as a human being. Where to draw the line?” said Zoloth, who is Jewish. “And it’s not a political question. It’s really a religious question.”

For many evangelicals and other Christians, IVF can be problematic, and some call for more regulation and education.

The process is “inherently unnatural,” and there are significant concerns relating to “the dignity of human embryos,” said Jason Thacker, a Christian ethicist who directs a research institute at the Southern Baptist Convention.

“I’m both pro-family and pro-life,” he said. “But just because we can do something, it doesn’t mean we should.”

Kelly and Alex Pelsor of Indianapolis turned to a fertility specialist after trying to have children naturally for two years. Doctors said her best chance for a baby was through IVF, which accounts for around two percent of births in the U.S.

“I was honestly very scared,” said Pelsor, who believes life begins as soon as growth starts after sperm and egg meet. “I didn’t know which way to go.”

Pelsor and her husband talked and prayed. She began attending a Christian infertility support group called Moms in the Making. She said she started to feel “this inexplicable peace about moving forward with IVF.”

Pelsor, 37, underwent a retrieval procedure in March 2021 and got five eggs.

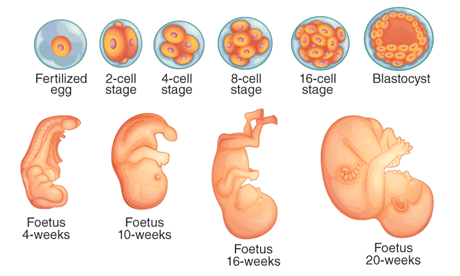

Three were able to be fertilised, and two embryos grew to the blastocyst stage and were able to be frozen. One was transferred to her womb in July 2021, and her daughter was born in March 2022.

“I truly believe she’s a miracle from God,” said Pelsor, who works for a nonprofit that includes a nondenominational church. “She would not be here without IVF.”

Pelsor miscarried the other embryo after it was transferred last year. So she never had to personally face the moral quandary of what to do with extras.

The moral quandrary

Amanda Walker of Albuquerque, New Mexico, did.

She and her husband turned to IVF after trying unsuccessfully to get pregnant naturally for five years and then having a miscarriage.

She wound up with 10 embryos. She miscarried five. Three became her children: an 8-year-old daughter and twins that will turn 3 in July.

That left her with two more, which she agonized and prayed about.

She said she often wonders how many other women find themselves in the same position she did after the egg retrieval, “where they’re just naive about the process in the beginning,” fertilizing too many eggs and then not knowing what to do.

“We didn’t want to destroy them,” said Walker, 42. “We believe that they are children.”

Considering the ethics of IVF

When Matthew Eppinette, a bioethicist, speaks about IVF, he hears many similar stories.

Couples tell him, “‘Well, we got way into the process, and we had these frozen embryos, and we just never realised that we were going to have to make decisions about this,’” said Eppinette.

He’s the executive director of the Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity at Trinity International University, an evangelical school based in Illinois.

“There’s a large educational component to this, both I think within the church, and maybe even within the medical community, to make sure that people are aware of what all is encompassed in IVF.”

Dr. John Storment, a reproductive endocrinologist in Lafayette, Louisiana, said he talks with patients about such issues, and some with similar beliefs about when life begins take steps to minimize or eliminate the risk of extra embryos.

For example, doctors can limit the number of eggs they’re likely to get by giving less ovary-stimulating medication. Or they can fertilize two or three eggs — hoping that one embryo grows — and freeze any other eggs.

If a few eggs need to be thawed and fertilised later, he estimated that would cost around $5,000 on top of the usual $15,000 to $25,000 for a round of IVF.

Another option is to transfer one or two embryos to the womb immediately without freezing any embryos or eggs. But if that doesn’t work, a patient could face another costly egg retrieval.

Thacker said that sort of “fresh” transfer is more ethically permissible than freezing embryos for an uncertain fate, “but I still don’t think it’s advisable.”

Religious scholars say the IVF issue is largely under-explored among evangelical Protestants, who lack the clear position against the procedure taken by the Catholic Church (even if individual Catholics vary in whether they adhere to the church’s teachings on reproductive ethics).

Still, Eppinette said most evangelical leaders would advise couples to create only as many embryos as they’re going to use and not leave any cryogenically frozen indefinitely.

In his own life, Eppinette goes further, saying “my personal conviction is against IVF.”

That’s why he and his wife weren’t willing to try it when they faced infertility in the 1990s and her one pregnancy ended in miscarriage.

Adopting the embryos created by IVF

Some couples and religious leaders find an answer in embryo adoption, a process that treats embryos like children in need of a home. Read more

- Laura Ungar is overs medicine and science on the AP’s global health and science team. She has been a health journalist for more than two decades.

- Tiffinay Stanley is a reporter and editor on The Associated Press’ global religion team.

Additional reading

News category: Analysis and Comment.