We reach the rock art caves and everyone falls silent. Later that night, the giant Northern Territory moon up and the mosquitoes and flies of all worlds swarming through the dark camp, the boys and the young men will talk of magic from up this hill and along the ridge where the rock art is. Kidney Fat Man and the Black Bushmen. Spirits that come to some but not others and come for both purposes: good and evil.

But for now we are up there, on the ridge, a drive and a hard walk from the camp through remote Northern Territory gums and pandanas, beneath squadrons of whistling kites, the scrubby ground crackling in the heat of the dry season. When we reach Yenmilli, the sacred rock art site, the boys and young men are suddenly still. They can talk all day and all night for hours on end in two languages and perhaps more, but not for now.

The sacred caves are small and under the crook of the ridge. The art is dots and hands, ancient and largely intact. Only one white person has seen it before, according to the family. Everyone sits. Black hands start tracing the white outlines on the cave walls and then black hands are placed over the drawn hands and most are an exact fit, like slipping into a glove.

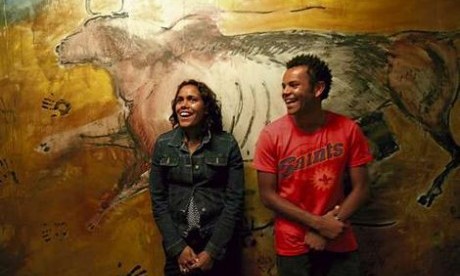

Jules Dumoo, the eldest of the nine Aboriginal men here, a father to some of them and also a brother and uncle and guardian, sits in the dirt of the first cave where kangaroos now live but where his ancestors did also. He’s only about 45 years old but his own uncles and his father are now gone. Continue reading

Sources

Additional reading

News category: Features.