In appointing seven women to the Vatican congregation that oversees religious orders July 9, Pope Francis achieved a double win.

In one stroke, he has advanced both the role of women in the church and the reform of the Vatican Curia.

This is significant because his efforts so far in these areas have been mediocre.

The Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life (CICLSAL), colloquially known as the Congregation for Religious, is responsible for setting policy for Catholic nuns, brothers and consecrated lay people.

Acting like a board of directors, members are appointed by the pope for terms of five years to review major policy recommendations before they are approved by the pope.

Six of the women were elected superiors by their religious orders, indicating the respect they have in their communities.

They are experienced and knowledgeable on the issues facing religious.

The seventh is the president of a group of consecrated lay people.

Of all the Vatican offices, CICLSAL is the one that most directly impacts religious women.

This is the office that instigated an infamous investigation of American nuns in 2008.

It is crucial that the congregation have diversity in its membership. For example, with women religious at the table, it will be impossible to ignore the issue of sexual abuse of sisters by priests.

In the past, the congregation was composed solely of cardinals, bishops and a few priests who were heads of religious orders.

It has had women on its staff and as advisers, but these seven women will have a vote when decisions are made.

However, they will be a minority of its membership with women only seven of the 23 new members appointed by Francis.

The appointment of women to the congregation is important because so far, progressive women have not been pleased with the pope’s handling of women’s issues.

While most women admire his pastoral style and concern for the poor and marginalized, many cringe when he talks about women.

He has referred to their role in the church as like strawberries on a cake.

He continues to use the language of complementarity that women found objectionable from John Paul II.

Francis opposes the ordination of women and supports the church’s traditional teaching on birth control.

For progressive women, he is the grandfather they love, but when he talks about women, they roll their eyes.

Francis may not be able to understand the language of feminism, but he has made incremental changes that advance the role of women in the church.

In 2014 he appointed five women to the Vatican’s International Theological Commission. Now he is adding women to a Vatican congregation.

The pace of change is still too slow, but it is moving in the right direction.

Francis is not intimidated by bright, strong women.

When as archbishop he opened an office dealing with human trafficking, the woman he put in charge said he was great: “He did whatever I told him.”

Every pope since the close of the Second Vatican Council in 1965 has tried unsuccessfully to reform the Vatican Curia, the administrative bodies that help the pope govern the church.

Pope Paul VI (1963-78) made the biggest changes by creating new offices to deal with issues like ecumenism.

He also instituted age limits, forcing heads of major offices to submit their resignations at age 75 and requiring members of congregations and councils to retire at age 80.

He also increased the size of the College of Cardinals to 120 voting members and took away a cardinal’s right to vote for a new pope when he turned 80.

Subsequent popes created additional offices and announced other reforms, but the basic organization of the Curia was left unchanged.

Francis, whose understanding of organizations and processes is not his strength, does understand the need to change the culture of the Curia.

He has repeatedly attacked clericalism and insisted that those working in the church should act like servants, not princes.

How successful these calls to conversion will be remains to be seen.

His reluctance to fire people limits his ability to control or replace his subordinates.

He has begun reorganizing and consolidating Curia offices in the hopes of improving coordination and downsizing.

But until he replaces the old guard with people sympathetic to his views, the actual impact of his reforms will be limited.

And while he has talked about allowing more local decisions, no list has been published of the issues that can now be dealt with by diocesan bishops and bishops’ conferences rather than in Rome.

The next step will be to appoint lay men and women to other congregations in the Vatican, including the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Congregation for Bishops.

Also, it would be good to see women appointed as heads of the Congregation for Religious and other congregations. And how about lay men and women as nuncios?

Change in these areas is slow under Francis, but there is hope if it continues to go in the right direction.

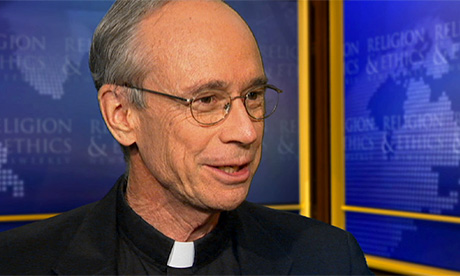

- Thomas Reese SJ is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.

News category: Analysis and Comment.