At the age of nine, Catholic priest and scholar James Alison realised two things.

The first was that he was gay.

The second was that his life would never be the same.

“I did know immediately that basically, I was lost,” he tells ABC RN’s Soul Search.

“I lost my parents’ world, their political world, their religious world.”

As a queer person in a religious environment, he felt alienated, an experience he’d spend the next few decades trying to understand.

His journey led him to religious orders in South America, to the forefront of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and to the work of a groundbreaking French philosopher, who helped him understand why some people scapegoat others.

Love could be real’

Dr Alison grew up in the UK with parents who were “hardline evangelicals” in the Anglican Church.

The family was also politically conservative; his father was a conservative member of the British Parliament and a minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government.

“[That’s] not a safe place to be if you’re a gay kid growing up, realising that you’re not fit for purpose in that world,” Dr Alison says.

At 18, after reading the biography of Italian Catholic priest and Saint Padre Pio, he found that Catholicism offered a different interpretation of the bible.

It made him feel able to accept both his sexuality and his relationship with God.

He converted to Catholicism, and four years later he joined a religious order in Mexico, where he began training to become a Catholic priest.

Part of his training involved pastoral work with people diagnosed with HIV and AIDS in the UK and Brazil, as the illness swept through queer communities across the world in the mid-1980s.

But while Catholicism had made him feel he could accept his own queerness, he saw serious shortcomings in the Church’s response to the AIDS crisis.

“At that time, the official language in the Catholic Church around gay love [described it as] hedonistic and self-centred,” Dr Alison says.

It didn’t align with the reality he’d observed.

He knew, from working with and counselling queer people facing serious health prognoses, that “[gay] love could be real” and, indeed, that it could be “stronger than death”.

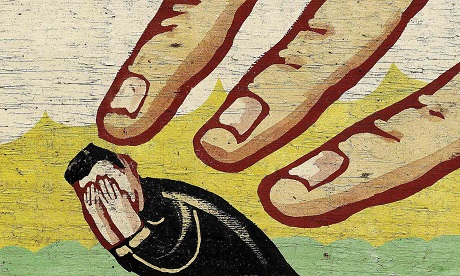

Dr Alison felt queer people were being targeted with the language of fear, but he couldn’t quite understand why.

The scapegoat

In the late 1980s, as Dr Alison continued his theological studies, he stumbled upon the work of French philosopher René Girard, known for his seminal work on the “scapegoat mechanism”.

Girard identified scapegoating as an important part of human adaptation.

Dr Alison, who went on to become an expert in the works of Girard, explains why:

“In situations of pressure, a group which is fighting amongst itself [and] which is full of rivalry, will mysteriously be able to move from an all-against-all to an all-against-one,” he says.

Girard’s theory is that the scapegoat is a “wrongly accused victim”, cast out “for the convenience of the group”, he says.

Girard argues that the result of that is increased group cohesion and a better chance at survival.

Dr Alison says it’s an age-old practice.

“The celebration of the survival of the group at the expense of a ‘wicked other’ has been absolutely part of human survival techniques and at the basis of so many mythologies all over the world,” he explains.

Indeed many scholars have identified this behaviour across cultures and even across species — studies have pointed to similar behaviour in primates.

Girard’s explanation of scapegoating behaviour had a profound impact on Dr Alison.

Suddenly, his own experiences and those he’d heard from the queer community fell into place: they had been scapegoats.

“[Girard] was saying something basically true about me and about the world that I knew,” he says.

A personal epiphany

The scapegoat concept can be traced back to the Bible.

In the Book of Leviticus, God instructs Aaron, the brother of Moses, to lay the sins of the Israelites on the head of a goat, then drive it “into the wilderness” to atone for their sins.

Even earlier in history, records of Ancient Greek and Middle Eastern rituals make mention of scapegoating, when a single individual — usually a slave, criminal or pauper — would be sacrificed or cast out in response to a societal ill.

For Dr Alison, the concept “turns on its head the old-fashioned [understanding] … of the death of Christ”.

Rather than seeing Jesus Christ’s death as a sacrifice to a wrathful God, Girard’s interpretation sees Christ as a scapegoat “created by us at our worst” — that is, the judgement and wrath comes from us, not God.

This understanding sees God as loving and compassionate, as he has self-sacrificially given over Christ as a way to meet our demand for violence once and for all.

Dr Alison believes understanding how and why we scapegoat allows us to empathise with minorities, rather than attack them. It also gives us power to push back against the status quo.

“It’s a fantastic piece of learning [to] automatically think, ‘Well, if the majority says it … then [they] must be right’.”

The psychology of scapegoating

Australian National University’s Benjamin Jones, an expert on the social psychology of scapegoating, says at its core scapegoating is a group response to a threat.

That threat can be real, like a food shortage or health crisis, or symbolic, like a threatened sense of group identity or nationalism.

Dr Jones says it’s about a group trying to determine and define their own identity.

“Once you exclude a particular [person or group], that does serve to intensify this understanding of what you’re like and who you are,” he says.

While scapegoating is a deeply ingrained “adaptive” human behaviour, he says it can also be co-opted for evil.

“The classic example is the Holocaust, [which saw] a subgroup being blamed for something without any evidence, and that being used to leverage a particular political interest.”

Plenty of minority groups have been subject to scapegoating in recent history, says Enqi Weng, a research fellow at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation at Deakin University.

From post-9/11 Islamophobia to anti-Asian sentiment through the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr Weng says there’s “a lot of overlap” between scapegoating and prejudice in Australian society. Continue reading

- Anna Levy has worked as a journalist and producer for news, local radio, television and national programs at ABC Brisbane. She is the deputy digital editor for Radio National.

- Rohan Salmond is a producer and presenter with ABC RN’s Religion and Ethics Unit.

News category: Analysis and Comment.