Catholics have been arguing about the Second Vatican Council—about what it did and didn’t do, about what it meant and still means or what it never meant and could never mean—for half a century. Many reform-minded Catholics today are disappointed by what they see as a retreat, under the papacies of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, from the council’s mandate for change, especially change in how the church is governed (see “Bishops or Branch Managers?”). Other Catholics, alarmed by the disarray that followed the council and mistrustful of attempts to reconcile Catholicism to a decadent, godless modern world, have applauded papal actions disciplining “dissenters” and reemphasizing traditional markers of Catholic identity. What reformers see as a rejection of the council’s promise of intellectual openness and ecumenism, traditionalists view as an indispensible move to safeguard truths of faith threatened as much from within the church as from outside it. Catholics who grew up after the council, meanwhile, often dismiss the polemics of both sides. To them, the changes that so disrupted the everyday lives of pre–Vatican II Catholics—the vernacular Mass with its visible role for the laity and particularly for women, the cataclysmic decline in vocations, the virtual disappearance of confession, the tolerance for public dissent from church teachings—are unremarkable, and comprise the only church they’ve ever known.

The result, it seems, is that there are currently several different, sometimes contending ways of being Catholic. To some degree that has always been so. The notion of the church as a rigorously disciplined and monolithic enterprise is largely myth, and modern myth to boot (see “An Imagined Unity”). What is not myth, however, is the dramatic change in the self-understanding of Catholics brought about by the council. For at least two centuries Catholicism saw itself as a bulwark against the spread of pernicious liberal and democratic principles, and held fast to a monarchical and aristocratic worldview in which the church enjoyed a privileged civic, cultural, and political role. At Vatican II, the bishops called off this long and ultimately futile struggle against modernity. Not without ambivalence, they reconciled themselves to the separation of church and state and to the idea of religious liberty (see “Outvoted, Not Persecuted”). They then went further, extending the hand of fellowship to other Christians, to non-Christian religions, and especially to the Jewish community, while warmly endorsing human rights and aspirations for democratic self-determination. Even the pursuit of technological and material progress, long viewed with world-weary skepticism, was encouraged. Read more

Sources

- Commonweal

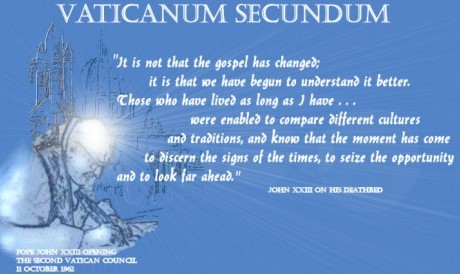

- Image: Vaticanum Secundum

Additional reading

News category: Features.