Young people are self-centred, self-interested and self-ish. They are ego and, ergo,

their world begins (and ends) with them. They are the i-Generation – emphasis on the “I”.

Maybe.

“Turn it off,” she said. “I can’t watch.”

My 11-year-old niece closed her eyes against the screen, blocking out the kids with no shoes, raincoats or lunch. My sister shrugged: “Don’t pretend you can’t see it. Do something.”

For the next six months, my niece sold foot-rubs and baking. She charged her mother $2 for vacuum cleaning, and when she got $50 for her birthday, put the lot towards her KidsCan fund.

Last year, she transferred $150 to the charitable trust that helps children whose lives bear no resemblance to her own.

I have never been more astonished. Or, it turns out, ignorant.

In 2016, Volunteering Auckland registered 711 people aged between 10 and 19 years – a 60 per cent increase on its 2013 figures.

The youth cohort is now the organisation’s third largest (the largest is 20-29-year-olds, those stereotypically self-absorbed millennials).

“I’ve been with Volunteering Auckland for 21 years,” says general manager Cheryll Martin. “I’ve always known the other side of the story about young people. They are the most innovative, energetic, passionate resource for our community. But they want connections and a feeling of belonging.

“What I’m seeing, is they’re not getting that personal connect from their devices. They’re

actually starting to look up from their devices.”

I was 32 when I got my first cellphone. My niece got her first at 12. Nobody under the age of 18 has lived in a world without Google and this is just-the-way-things-are. But what if teenagers want – and need – more?

The modern adolescent has never had more “friends”. Conversely, they have never felt so isolated. Families are scattered, wealth is distributed unevenly and teenagers must compete to survive, let alone thrive.

Their world is changing hard and fast and they’re following it live and as it happens. They know about the Syrian refugee crisis and the Paris terror attacks.

They know that, in December, a 12-year-old American girl live-streamed her suicide. And they knew, long before “Roastbusters” entered the parental vernacular, that there were teenagers who got drunk at parties and others who took out their phones and filmed what happened next.

What they’re less clear about: how to make sense of all this. Continue reading

Sources

- NZ Herald, article by Kim Knight, a writer for NZME’s Canvas and Weekend magazines.

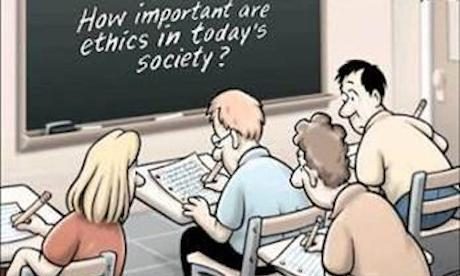

- Image: Berkeley Office of Ethics

News category: Features.