The appeal of the Olympics is that they decide who can claim the title of best in the world. They also, less gloriously, decide who can claim the title of second best in the world.

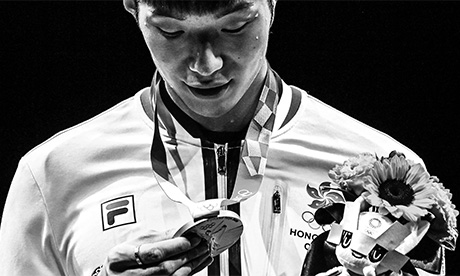

Despite beating out every competitor on Earth but one, silver medalists can feel a special type of disappointment.

In a study that analyzed footage from the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, they were consistently judged to look less happy than bronze medalists, both right after competition and atop the medal podium.

The explanation, the researchers theorized, was that the athletes were dwelling differently on what might have been: The silver medalists were wondering how great winning gold might have felt, while the bronze medalists were contemplating the letdown of not medaling at all.

The Olympics may have more pageantry, nationalism, and breathless TV commentators than daily life does, but the Games hold lessons about how achievement and its pursuit affect our happiness—even those of us who aren’t competing to be the world’s best at anything.

What the Olympics teach us is that although the promise of achievement can propel us forward, it comes with pitfalls that can undermine the satisfaction of actually achieving.

So should we all try to be more like the bronze medalists and focus on how things could be worse?

Not always, Tom Gilovich, a psychology professor at Cornell University and a co-author of the study, told me.

While these “downward” comparisons can make people feel better, he pointed out that sometimes-dispiriting “upward” comparisons can motivate people to work harder on things they care about.

Each mindset has its benefits and drawbacks, so a prudent approach might be to strategically toggle between them.

No one has studied how athletes’ results at the Olympics affect their long-term well-being, but Gilovich hypothesizes that over time, the sting of not winning gold would tend to fade in importance relative to the satisfaction of having gone to the Games.

Unfortunately, the gratification of attending will probably be little consolation to the athletes who have had to pull out of this year’s contest after getting COVID-19.

And in some cases, the emotions of competition can stay raw for a long time: Abel Kiviat, an American who led the 1,500-meter race at the 1912 Olympics until another runner overtook him by surprise eight meters from the finish line, told an interviewer decades later, “I wake up sometimes and say, ‘What the heck happened to me?’”

He was 91 at the time of the interview, some 70 years removed from the race.

The sneaky Brit who beat Kiviat by one-tenth of a second was surely thrilled, but winning a gold medal presents its own distinct set of challenges.

Even being the greatest in the world doesn’t guarantee lasting contentment. Because of what researchers call “hedonic adaptation,” your happiness eventually tends to revert to a baseline level after a good (or bad) thing happens to you.

“Even something as amazing as getting a huge raise at work; as meeting the love of your life; as, potentially, winning a gold medal—we get used to it, because we’re not focused on it day in and day out,” Cassie Mogilner Holmes, a professor at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, told me.

The pursuit of gold medals and other dreams can be draining as well as energizing.

One difficulty, as Holmes pointed out, is that chasing a goal for the sake of glory or money (extrinsic motivations) can undermine your original passion for an activity (an intrinsic motivation).

Intrinsic motivations, she said, tend to bring people more happiness than extrinsic ones.

“This Olympic Games, I wanted it to be for myself when I came in—and I felt like I was still doing it for other people,” the star American gymnast Simone Biles said after withdrawing from competition this week for the sake of her mental and physical health.

Not only is this decision likely to protect her well-being, but research suggests it might also protect her relationship with the sport she loves.

Another challenge for Biles, who had won four gold medals in 2016, might have been “the very different psychology involved when one is already at the pinnacle, and therefore is ‘playing not to lose,’ versus when one is trying to get to the pinnacle and is playing to win,” Gilovich said.

“The former is so much more stressful and difficult than the latter.”

The decorated American swimmer Mark Spitz, who won seven gold medals in Munich in 1972, articulated this anxiety before his seventh race that year: “If I swim six and win six, I’ll be a hero. If I swim seven and win six, I’ll be a failure.”

Whatever happens during competition, Olympians can experience a brutal comedown once the Games are over.

Several athletes, including the American gold-medalist swimmers Michael Phelps and Allison Schmitt, have said that they experienced depression after their successes.

In a blog post titled “Post-Olympic Stress Disorder,” the American judo competitors Taraje Williams-Murray and Rhadi Ferguson, who were teammates in 2004, wrote that life after the Games could feel “sickeningly mundane” and was “a lot different than viewing the world from the lofty vantage point of ‘Mount Olympics.’”

Competing at the very highest level can leave some athletes feeling as though they’ve peaked and don’t have a next logical goal to pursue. Continue reading

Additional readingNews category: Analysis and Comment.