Income and wealth inequality has risen in many countries in recent decades.

Rising inequality and related disparities and anxieties have been stoking social discontent and are a major driver of the increased political polarisation and populist nationalism that are so evident today.

An increasingly unequal society can weaken trust in public institutions and undermine democratic governance.

Mounting global disparities can imperil geopolitical stability.

Rising inequality has emerged as an important topic of political debate and a major public policy concern.

High and rising inequality

Current inequality levels are high.

Contemporary global inequalities are close to the peak levels observed in the early 20th century, at the end of the prewar era (variously described as the Belle Époque or the Gilded Age) that saw sharp increases in global inequality.

Over the past four decades, there has been a broad trend of rising income inequality across countries.

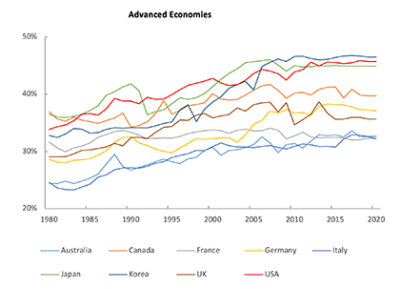

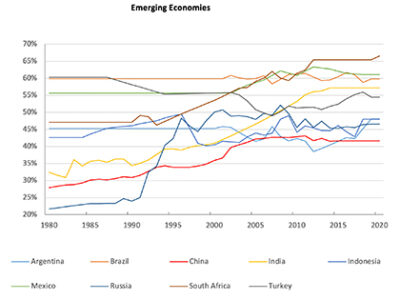

Income inequality has risen in most advanced economies and major emerging economies, which together account for about two-thirds of the world’s population and 85 percent of global GDP (Figure 1).

The increase has been particularly large in the United States, among advanced economies, and in China, India, and Russia, among major emerging economies.

Beyond these groups of countries, the trend in the developing world at large has been more mixed, but many countries have seen increases in inequality.

In regions such as Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa, income inequality levels on average have been relatively more stable, but inequality was already at high levels in these regions—the highest in the world.

Wealth inequality within countries is typically much higher than income inequality.

It has followed a rising trend across countries since around 1980, similar to income inequality.

Higher wealth inequality feeds higher future income inequality through capital income and inheritance.

Figure 1. Inequality has risen in most advanced and major emerging economies

Richest 10% income share, 1980-2020

Source: Author, using data from World Inequality Database.

Note: Pre-tax national income. Some data points are extrapolated.

The increase in inequality has been especially marked at the top end of the income distribution, with the income share of the top 10 percent (and even more so that of the top 1 percent) rising sharply in many countries.

This was so particularly up to the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

Those in low- and middle-income groups have suffered a loss of income share, with those in the bottom 50 percent typically experiencing larger losses of income share.

These trends in inequality have been associated with an erosion of the middle class and a decline in intergenerational mobility, especially in advanced economies experiencing larger increases in inequality and a greater polarization in income distribution.

While within-country inequality has been rising, inequality between countries (reflecting per capita income differences) has been falling in recent decades.

Faster-growing emerging economies, especially the large ones such as China and India, have been narrowing the income gap with advanced economies.

Global inequality—the sum of within-country and between-country inequality—has declined somewhat since around 2000, with the fall in between-country inequality more than offsetting the rise in within-country inequality.

As within-country inequality has been rising, it now accounts for a much larger part of global inequality (about two-thirds in 2020, up from less than half in 1980).

Looking ahead, how within-country inequality evolves will matter even more for global inequality.

The interplay between the evolution of within-country inequality and between-country inequality, coupled with the differential growth performance of emerging and advanced economies, in recent decades presents an interesting picture of middle-class dynamics at the global level (as depicted by the well-known “elephant curve” of the incidence of global economic growth). It shows, for the period since 1980, a rising middle class in the emerging world and a squeezed middle class in rich countries.

It also shows an increasing concentration of income at the very top of the income distribution globally.

Drivers of rising inequality

Shifting economic paradigms are altering distributional dynamics. Transformative technological change, led by digital technologies, has been reshaping markets, business models, and the nature of work in ways that can increase inequality within economies.

While the specifics differ across countries, this has been happening broadly through three channels. Continue reading

Additional readingNews category: Analysis and Comment, Palmerston.