We are called to walk on the synodal way in friendship. Otherwise, we shall get nowhere.

Friendship, with God and each other, is rooted in the joy of being together but we need words.

At Caesarea Philippi, conversation broke down. Jesus had called Peter ‘Satan’, enemy.

On the mountain, he still does not know what to say but they begin to listen to him and so the conversation can begin again as they journey to Jerusalem.

On the way, the disciples quarrel, misunderstand Jesus, and eventually desert him. Silence returns. But the Risen Lord appears and gives them words of healing to speak to each other.

We too need healing words that leap cross the boundaries that divide us: the ideological boundaries of left and right; the cultural boundaries that divide one Continent from another, the tensions that sometimes divide men and women.

Shared words are the lifeblood of our Church. We need to find them for the sake of our world in which violence is fueled by humanity’s inability to listen. Conversation leads to conversion.

How should conversations begin?

In Genesis after the Fall, there is a terrible silence. The silent communion of Eden has become the silence of shame.

Adam and Eve hide. How can God reach across that chasm? God waits patiently until they have clothed themselves to hide their embarrassment. Now they are ready for the first conversation in the Bible.

The silence is broken with a simple question: ‘Where are you?’

It is not a request for information. It is an invitation to step out into the light and stand visibly before the face of God.

Perhaps this is the first question with which we should break the silences that separate us.

Not: ‘Why do you hold these ridiculous views on liturgy?’ Or ‘Why are you a heretic or a patriarchal dinosaur?’ or ‘Why are you deaf to me?’

But ‘Where are you?’ ‘What are you worried about?’

This is who I am. God invites Adam and Eve to come out of hiding and be seen.

If we too step out into the light and let ourselves be seen as we are, we shall find words for each other.

In the preparation for this Synod, often it has been the clergy who have been most reluctant to step out into the light and share their worries and doubts.

Maybe we are afraid of being seen to be naked. How can we encourage each other not to fear nakedness?

After the Resurrection, the silence of the tomb is again broken with questions.

In John’s gospel, ‘Why are you weeping?’ In Luke, ‘Why do you look for the living among the dead?’

When the disciples flee to Emmaus, they are filled with anger and disappointment.

The women claim to have seen the Lord, but they were only women. As today sometimes, women did not seem to count!

The disciples are running away from the community of the Church, like so many people today.

Jesus does not block their way or condemn them.

He asks ‘What are you talking about?’ What are the hopes and disappointments that stir in your hearts?

The disciples are speaking angrily. The Greek means literally, ‘What are these words that you are hurling at each other?’

So Jesus invites them to share their anger. They had hoped that Jesus would be the one to redeem Israel, but they were wrong.

He failed. So, he walks with them and opens himself to their anger and fear.

Our world is filled with anger. We speak of the politics of anger. A recent book is called American Rage.

This anger infects our Church too.

A justified anger at the sexual abuse of children. Anger at the position of women in the Church. Anger at those awful conservatives or horrible liberals.

Do we, like Jesus, dare to ask each other: ‘What are you talking about? Why are you angry?’ Do we dare to hear the reply?

Sometimes I become fed up with listening to all this anger. I cannot bear to hear any more. But listen I must, as Jesus does, walking to Emmaus.

Many people hope that in this Synod their voice will be heard. They feel ignored and voiceless. They are right. But we will only have a voice if we first listen.

God calls to people by name. Abraham, Abraham; Moses, Samuel. They reply with the beautiful Hebrew word Hinneni, ‘Here I am’.

The foundation of our existence is that God addresses each of us by name, and we hear. Not the Cartesian ‘I think therefore I am’ but I hear therefore I am.

We are here to listen to the Lord, and to each other. As they say, we have two ears but only one mouth! Only after listening comes speech.

We listen not just to what people are saying but what they are trying to say. We listen for the unspoken words, the words for which they search.

There is a Sicilian saying: “La miglior parola è quella che non si dice’[1] ‘The best word is the one that is not spoken’.

We listen for how they are right, for their grain of truth, even if what they say is wrong. We listen with hope and not contempt.

We had one rule on the General Council of the Dominican Order. What the brethren said was never nonsense. It may be misinformed, illogical, indeed wrong. But somewhere in their mistaken words is a truth I need to hear.

We are mendicants after the truth. The earliest brethren said of St Dominic that ‘he understood everything in the humility of his intelligence’[2].

Perhaps Religious Orders have something to teach the Church about the art of conversation.

St Benedict teaches us to seek consensus; St Dominic to love debate, St Catherine of Siena to delight in conversation, and St Ignatius of Loyola, the art of discernment. St Philip Neri, the role of laughter.

If we really listen, our ready-made answers will evaporate. We will be silenced and lost for words, as Zechariah was before he burst into song.

If I do not know how to respond to my sister or brother’s pain or puzzlement, I must turn to the Lord and ask for words. Then the conversation can begin.

Conversation needs an imaginative leap into the experience of the other person.

To see with their eyes, and hear with their ears. We need to get inside their skin. From what experiences do their words spring? What pain or hope do they carry? What journey are they on?

There was a heated debate on preaching in a Dominican General Chapter over the nature of preaching, always a hot topic for Dominicans!

The document proposed to the Chapter understood preaching as in dialogical: we proclaim our faith by entering into conversation.

But some capitulars strongly disagreed, arguing this verged on relativism.

They said ‘We must dare to preach the truth boldly’. Slowly it became evident that the quarrelling brethren were speaking out of vastly different experiences.

The document had been written by a brother based in Pakistan, where Christianity necessarily finds itself in constant dialogue with Islam.

In Asia, there is no preaching without dialogue.

The brethren who reacted strongly against the document were mainly from the former Soviet Union. For them, the idea of dialogue with those who had imprisoned them made no sense.

To get beyond the disagreement, rational argument was necessary but not enough.

You had to imagine why the other person held his or her view. What experience led them to this view? What wounds do they bear? What is their joy?

This demanded listening with all of one’s imagination.

Love is always the triumph of the imagination, as hatred is a failure of the imagination. Hatred is abstract. Love is particular.

In Graham Greene’s novel The Power and the Glory, the hero, a poor weak priest, says: ‘When you saw the lines at the corners of the eyes, the shape of the mouth, how the hair grew, it was impossible to hate. Hate was just a failure of imagination.’

We need to leap across the boundaries not just of left and right, or cultural boundaries, but generational boundaries too.

I have the privilege of living with young Dominicans whose journey of faith is different from mine.

Many religious and priests of my generation grew up in strongly Catholic families. The faith deeply penetrated our everyday lives.

The adventure of the Second Vatican Council was in reaching out to the secular world. French priests went to work in factories. We took off the habit and immersed ourselves in the world.

One angry sister, seeing me wearing my habit, exploded: ‘Why are you still wearing that old thing?’

Today many young people – especially in the West but increasingly everywhere – grow up in a secular world, agnostic or even atheistic.

Their adventure is the discovery of the gospel, the Church and the tradition. They joyfully put on the habit. Our journeys are contrary but not contradictory. Read more

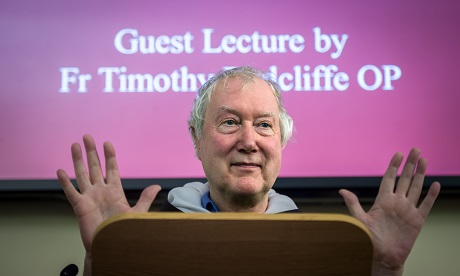

- Father Timothy Radcliffe, OP, is an English Catholic priest and Dominican friar who served as master of the Order of Preachers from 1992 to 2001. This is the final part of the reflection he shared on Sunday with those about to attend the General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops, which began yesterday.

Additional reading

News category: Analysis and Comment.