The synodal process has shown a concerning lack of rigorous theological examination of the liturgy—both its theological essence and its ritual execution—leading to debates and speculative discussions that hinder the Church’s progress.

This deficiency is starkly highlighted in paragraphs 26-28 of the Synod’s Final Document.

The document equates Eucharistic and synodal assemblies as manifestations of Christ’s presence and the Spirit’s unifying work.

It also highlights “listening” as a common trait in both.

This creates a flawed equivalence that must be addressed before any working group defines the “celebratory styles that make visible the face of a synodal Church.”

This simplification risks diminishing the depth of liturgical rites.

It can obscure their true ritual essence and misinterpret their theological meaning.

While linking synodality with the liturgy is invaluable, such parallels risk reducing the unique purposes of each.

The Eucharist is the focal point of sacramental unity and divine encounter, whereas synodal gatherings are primarily deliberative, geared towards consensus and the governance of ecclesial life.

Treating them as equivalents risks blurring their distinct theological identities, diminishing their respective roles as the lived expression of

- prayerful faith (liturgy) and

- the organisational manifestation of faith in action (mission and management).

Moreover, practical challenges, such as the diverse cultural interpretations of synodality and its application to liturgical practice, remain inadequately explored.

Responding to the “signs of the times” within a liturgical context means prioritising the centrality of the assembly meeting for worship (Synaxis).

It is the Synaxis that informs and underpins the synodal processes, not the other way around.

The liturgy derives its meaning from its direct relation to the Paschal Mystery, serving as its memorial in a liturgical context.

Unlike the synodal process, the liturgical Synaxis uniquely represents and re-presents this Mystery. So it is troubling, though not unexpected, that liturgical theologians are conspicuously absent from the synodal dialogue.

Consequently, significant sacramental and liturgical questions remain neglected, approached only from tangential perspectives.

This oversight occurs when auxiliary theological disciplines and Canon Law, a non-theological field, marginalise the primary discipline of liturgical theology.

The synodal discussions commendably focused on dialogue, inclusivity, and governance reform, have largely sidestepped the liturgy despite its pivotal role in Catholic life.

This sidestepping can be attributed to several factors.

The synodal agenda primarily addresses structural and cultural challenges within the Church, such as clericalism and lay participation.

These efforts are necessary for cultivating an inclusive Church that listens to and integrates the experiences of all its members, especially those who feel alienated.

Within this framework, liturgy often becomes a secondary concern, perceived merely as ritual or ceremonial, with little attention given to its deeper theological dimensions rooted in baptismal ontology.

Moreover, liturgical discourse is inherently contentious.

Decades of “liturgy wars” over issues such as the use of Latin, lay participation, and other practices have sown division between traditionalist and progressive camps.

This contentious history makes many Church leaders hesitant to reopen discussions that could reignite conflict and detract from the Synod’s wider objectives of unity and reform.

The liturgy, firmly anchored in tradition and doctrine, presents a complex area for reform.

The Eucharist, as the “source and summit” of Christian life, is integral to Catholic identity. Therefore, conversations around liturgical change touch upon fundamental theological beliefs and ecclesial authority.

The spectre of perceived challenges to doctrine makes some prelates wary of undertaking such discussions, fearing potential disquiet among the faithful.

There are also voices within the Church who believe synodality, by influencing the values of unity and inclusivity in governance, will naturally extend these values into the liturgy without requiring direct liturgical reform.

This perspective avoids more profound theological questions of baptismal ontology, sidestepping the liturgical implications of issues like the ordination of women or blessings of non-canonical unions.

While the Synod’s Final Document calls for the liturgy to embody the synodal principles of dialogue and inclusivity, it overlooks the pressing reality many parishes face: an “eucharistic and sacramental famine.”

Even as synodal efforts remain focused on governance and pastoral strategies, the central Synaxis—the heart of ecclesial life—weakens under the weight of scarcity.

Many communities endure prolonged periods without access to sacramental celebrations due to an entrenched prioritisation of celibacy over Eucharistic necessity.

This imbalance has led to a phenomenon where clergy from Africa and Asia are brought in to sustain sacramental life, a practice that increasingly resembles a form of “reverse colonisation” with significant consequences already emerging.

In such a landscape, the liturgy is often appropriated as a stopgap solution, a practice born out of necessity when leadership fails to address these pressing realities adequately.

Addressing this issue is vital, for without a robust Synaxis, there will inevitably be no meaningful synodos.

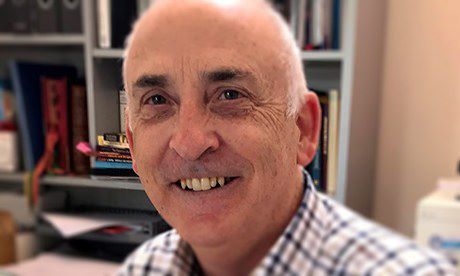

- Dr Joe Grayland is priest of the Catholic Diocese of Palmerston North (New Zealand) for nearly 30 years. He is currently an assistant lecturer in the Department of Liturgy, University of Wuerzburg (Germany).

- A version of this opinion piece originally appeared on La Croix International.

News category: Analysis and Comment.