The economic downturn caused by Covid-19 has had an uneven impact, in part reflecting the unprecedented nature of the crisis.

The housing market and many domestic-orientated industries are doing well. And for many households and businesses, the economic downturn has so far had little impact on job security, incomes, or spending.

For some, the increased prevalence of flexible and remote working has even brought a welcome breath of fresh air.

But some pockets of the economy have been hit relatively hard. Those industries exposed to tourism have seen unprecedented challenges, despite a cushion from the captive domestic tourism market through winter and the wage subsidy.

The international education industry is facing a massive hole, and industries like horticulture reliant on overseas labour are facing significant problems.

The impact on the labour market has been uneven too, with 31,000 fewer people in employment compared with March – and a massive blow has been seen in retail, accommodation and food services in particular (where there are now 29,000 fewer people employed than in March.

Women more affected

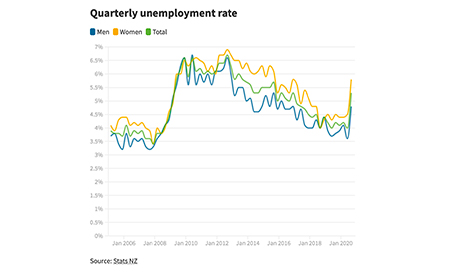

But the uneven impact hasn’t just been by industry. Job losses are unfortunately rising, and so far the impact of that has been felt disproportionately by women.

Since March, women have experienced 71 per cent of the decline in employment (with 22,000 fewer women employed). Some of this may be voluntary, with 4000 fewer women in the labour force, who are no longer ready, willing, or able to work.

For these women, retirement, working in the home or other unpaid work may be a preferred option. But others may not be participating because they are discouraged about their job prospects.

This possibility is concerning, particularly if it becomes entrenched and productive workers, income potential and valuable skills are lost.

The “voluntary” dynamic is only a modest part of the story at best.

The fact is we know that there are now many more women who are not in work but would like to be.

The number of women who meet the definition of “unemployed” – ready, willing and able to work – has increased by 19,000 since March. This has seen the female unemployment rate rise from 4.4 per cent to 5.8 per cent (compared with an increase from 4.1 per cent to 4.8 per cent for men).

In addition to the extra 19,000 women who are now unemployed relative to March, there are also more women in employment who would like to work more hours but can’t (23,000 women). Taking this into account, the female underutilisation rate is sitting at 16.2 per cent, compared with 10.6 per cent for men.

Women tend to work in lower-paid jobs on average, with average hourly earnings about 10 per cent lower than those for men (not adjusting for job type and the like).

That means that the income effects of this crisis have been uneven too. In aggregate, incomes have been cushioned by things like the wage subsidy and the blow has been nowhere near as bad as it could have been.

But some people are nonetheless much worse off than they were before, and so far the impact appears to be skewed towards those with lower-paid jobs.

Why have women seen such an impact? There appear to be two parts to the story. Continue reading

Additional readingNews category: Analysis and Comment.