In late March of this year, the Vatican formally — and somewhat surprisingly — repudiated the centuries-old “Doctrine of Discovery,” based on papal dictates of the 15th century that justified the domination of newly “discovered” lands and peoples by European Christian explorers.

Indigenous activists and organisations in North America were pleased but ultimately underwhelmed by the Vatican’s move, however, as the formal statement failed to submit the Roman Catholic Church to any accountability for the extensive harm the doctrine caused over the centuries — colonisation itself, as well as the motivating values and beliefs inherent in the Doctrine of Discovery that continued well after the first several centuries of active colonialism and conquest declined.

The repudiation, which came in a statement from a bureaucratic office, not Pope Francis himself, said the doctrine had been “manipulated” by colonisers “to justify immoral acts against Indigenous peoples that were carried out, at times, without opposition from ecclesiastical authorities.”

Native Americans also felt the statement downplayed the Catholic Church’s active role in driving the colonisation and destruction of Indigenous populations.

The real question is, how much can we expect such a statement to change long-held attitudes regarding the right of European Christians to displace and destroy Indigenous peoples in centuries past?

Indigenous advocates’ fears about the lack of a long-term impact appear well-founded. Surveys of the American public demonstrate that the influence of the theological justifications for dominion and violence created by the Doctrine of Discovery is still strong, primarily through the cultural framework of Christian nationalism.

Christian nationalism is the desire to see a particular expression of the Christian faith fused with American civic life and identity.

Christian nationalism regards its version of Christianity as the principal and undisputed moral and cultural framework in the United States and prefers a government that vigorously preserves it.

In 2023, a survey on Christian nationalism in the United States from the Public Religion Research Institute and The Brookings Institution measured the prevalence of Christian nationalism by gauging how much Americans agreed with the following five statements:

- The U.S. government should declare America a Christian nation. U.S. laws should be based on Christian values.

- If the U.S. moves away from our Christian foundations, we will not have a country anymore.

- Being Christian is an important part of being truly American.

- God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society.

Those who agree or strongly agree with these statements score higher on the scale, while those who disagree or strongly disagree score lower on the scale.

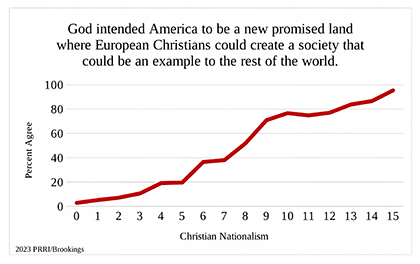

As the figure below clearly shows, Christian nationalism is intimately intertwined with the belief that God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society to serve as an example to the rest of the world.

“God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society that could be an example to the rest of the world” Graphic courtesy of Andrew Whitehead

Americans who embrace Christian nationalism are much more likely agree that God destined America to be a new “promised land” for European Christians. Furthermore, Christian nationalism considers these European Christians as tasked with creating a society that would be “a shining city on a hill,” in the words of Ronald Reagan, echoing Puritan leader John Winthrop.

The declarations of the Doctrine of Discovery were the earliest iterations of many of these ideas and formed a theological foundation for the white Christian nationalism we see in our body politic today.

The Doctrine of Discovery created a binary society of European Christians on the one hand and those deserving of domination on the other. Only such a society would align with the will of the Christian God.

This theology survived the Reformation and its cleaving of Christianity.

The Protestant sect we call the Puritans viewed themselves as special in the eyes of the Christian God, a status that justified their forceful occupation and seizure of land, resources, and people in North America.

As Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah write in their 2019 book Unsettling Truths, “The Doctrine of Discovery allowed Native genocide to be understood as a holy act of claiming the promised land for European settlers.”

After a massacre of hundreds of Pequots in 1637, one captain of colonial forces declared, quoting Psalm 110, “thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen.”

Beyond baptising the use of violence to take hold of the “promised land,” the Doctrine of Discovery implicitly required settlers to distinguish “us” from “them,” encouraging the creation of racial categories in North America. European Christians quickly differentiated themselves from the Indigenous people they encountered and those they brought to these shores as slaves. White skin signalled good and Christian, while black or brown skin signified bad and heathen.

This fruit of the doctrine is still with us today.

Americans who embrace Christian nationalism are much more likely to deny the reality of racial injustice, view authoritarian violence towards minorities as justified and view racial diversity as a greater hindrance to national unity than even religious diversity.

At its root, Christian nationalism idolises self-interested power, fear of outsiders and violence towards those who threaten the boundaries between “us” and “them.” The Doctrine of Discovery was essential to creating these idols of Christian nationalism.

And as the heinous actions of those expounding the doctrine throughout history show us, quests to protect self-interested power based on hierarchical relationships between “us” and “them”— founded on fear of “them” — usually result in violence.

While the statement from the Vatican is an important step, Indigenous activists point out that more direct action from the Catholic Church is necessary to repair prior wrongs, perhaps in the form of reparations for those communities most harmed by the Doctrine of Discovery.

At the very least, the church can speak out against the cultural framework of Christian nationalism.

Otherwise, those who believe God promised this land and its fruits to our forebears will remain convinced of their right to allow nothing — not even those who were here long before — to stand in their way.

- Andrew Whitehead is an author at Religion News Service.

- First published in RNS. Republished with permission.

News category: Analysis and Comment.