Lil Nas X, Bad Bunny and Princess Nokia all work their spirituality into their music, but you’re not likely to think of them as virginal.

They are nonetheless helping to spread a craze for Mary, mother of Jesus, wearing designer Brenda Equihua’s splashy coats made from San Marcos cobijas: blankets found in many Latinx homes that commonly feature the Virgin of Guadalupe.

For Equihua, Mary’s appeal is partly sentimental.

Of Mexican American heritage, Equihua identifies the Virgin of Guadalupe with home.

But there’s something deeper than simple nostalgia going on in her designs.

“Wearing Mary in a fashion piece is unexpected,” she explained. “I think what’s cool is taking something out of context.”

Religious figures are often (if scandalously) appropriated outside sacred settings, but the decontextualization of Mother Mary has been in hyperdrive of late.

Long a fixture on devotional medals worn by Catholics, Mary is so central to Catholic spirituality that Pope Francis earlier this year had to debunk the notion that Jesus’ mother would be designated “co-redemptrix”: “Mary Saves” tees are not coming to the St Peter’s gift shop.

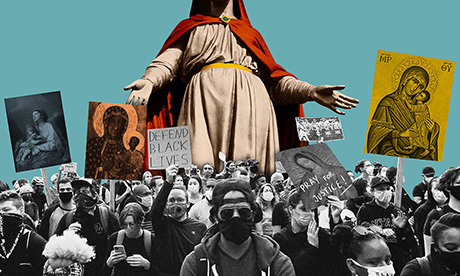

But if Catholics are content with her place as “a Mother, not as a goddess,” as the pope put it, Mary has become an icon to a younger generation of all faiths and no faith that has put social justice at the centre of its hopes for a better world.

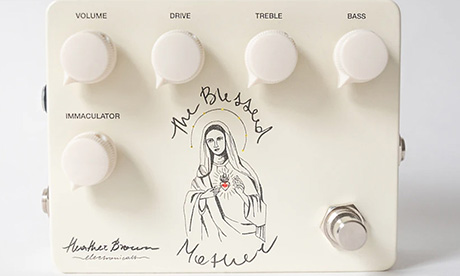

The Blessed Mother guitar pedal created by Heather Brown.

She’s treated as a feminist beacon, her likeness appearing alongside that of Frida Kahlo, Joan of Arc and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Mary lends cred to high-end guitar pedals created by female gear makers and pops up with increasing frequency on Etsy.

Her story is being retold in provocative contemporary art and the theses of up-and-coming scholars.

But for all her trendiness, what makes Mary an appealing figure today is what has made her popular for 2,000 years: For all her connections to divine power, she has a lot in common with people who often get overlooked.

Mary has become an icon to a younger generation of all faiths and no faith that has put social justice at the centre of its hopes for a better world.

Ben Wildflower is a mail carrier by day and artist in his off-hours.

In 2017, he made a woodcut that showed Mary, her fist raised over her head, feet resting on a skull and a serpent (the former is a motif usually associated with Jesus’ disciple Mary Magdalene, while the latter is in keeping with historical representations of Mary, Jesus’ mother, triumphing over original sin).

In a circle around Wildflower’s image are the words “Fill the hungry. Cast down the mighty. Lift the lowly. Send the rich away.”

When he posted it on Instagram, it went viral.

Some critics called the woodcut’s message “un-Christian,” protesting that “God loves everyone.”

The taunting language, however, was pulled directly from the Magnificat, the gospel writer Luke’s version of a song attributed to Mary, that from earliest Christian times was seen as so revolutionary public readings of it have been banned in the past.

Wildflower, the child of evangelical Christian missionaries, now attends an Anglican church, is committed to living in solidarity with the poor and has been described as a “Christian anarchist.”

He finds himself deeply drawn to the mother of Jesus and said he likes Mary’s vision of hierarchies being turned upside down.

Non-Christians, he said, are often interested in his work on Mary as a way of “seeking the divine feminine” via a sort of “DIY spirituality.”

Further evidence of this approach can be found on sites such as Etsy, which sells Mother Mary oracle cards and altars for charging “reiki-energized” crystals that feature Mary’s likeness.

“Sometimes I’ll realize I have an influx of followers on Instagram and I’ll try to figure out what happened and it’ll be from like, a witchcraft and herbal kind of account,” Wildflower added.

But for Wildflower, Mary is a bridge to a Christianity far from his evangelical upbringing.

“For a lot of people who were raised in white evangelical culture, God’s representatives throughout most of our lives had not been the best people,” Wildflower explained, “but Mary’s representatives were just kind of absent.

So it’s not hard to relate to her as someone saying, ‘It’s our job to bring God into the world.’

There’s something relatable there because there’s no baggage.”

(For a clue to what kind of baggage he’s trying to leave behind, look no further than another Wildflower illustration that depicts Mary shooting flames out of her hands at Nazi and Confederate flags, encircled by the words “O Mary, conceived without white supremacy, pray for us trying to dismantle this s_t.”)

Catholic author and University of California, Berkeley lecturer Kaya Oakes is not surprised by the new attention paid to Mary, noting that her appeal tends to grow when times are hard.

“Mary represents this side of God that is nurturing and will stay with you when you’re in pain,” Oakes said.

“We’re coming out of this really traumatic phase in world history with the pandemic, and people have needed images of God that were more resonant with that compassionate, rather than judgmental, side of the divine.”

A Virgin Mary inspired dress stands on display in the front window of a shop in Rehoboth, Delaware in March 2021.

Mary traditionally shows up whenever she is most needed.

For years, apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe have reportedly distracted border guards to help immigrants stranded at the U.S. border slip into the country unnoticed. Similarly, the culture tends to put Mary at the centre of the conflict.

After Mike Brown was shot in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, Mark Doox’s “ Our Lady of Ferguson” depicted her as a Black woman with her womb in the crosshairs of a gun with a child Christ in the centre.

Kehinde Wiley’s “Mary Comforter of the Afflicted,” one of the artist’s stained glass window images, casts the Pietà as a Black man holding a dead child.

Within the past year, Kelly Latimore’s icon memorialized George Floyd by depicting Mary holding a broken Jesus.

Amey Victoria Adkins-Jones, an assistant professor in the theology department of Boston College whose scholarship focuses on Mariology, said these artists are pulling from a long tradition of Black Madonnas.

Though Adkins-Jones was raised Southern Baptist in a setting where Mary got little attention, her experiences with the Black Madonna helped convince her that the mother of Jesus is an underutilized resource for grappling with Black womanist concerns in Christian theology.

“This imagery captures the legacy of grief that comes from injustice,” said Adkins-Jones.

“Perhaps Mary is a ready figure to call to memory because Jesus is a person who dies unjustly at the hands of the state. … Questions of justice are always in conversation with artistic representations.”

Adkins-Jones also sees Mary inviting theological questions about gender.

As a young, poor woman giving birth in an occupied land, the historical Mary experienced a kind of precarious existence that can’t be disconnected from her womanhood, Adkins-Jones said.

Looking to Mary invites both a new kind of intellectual curiosity and spiritual reflection on the role of women in the world.

For all the seemingly renewed interest in Mary, Adkins-Jones notes that some of it aren’t so much new as a continuing tradition now aided by platforms such as Instagram that allow for fresh ways to “visually discuss.”

Still, according to associate professor of art history at Wheaton College Matthew Milliner, there is a kind of change afoot. When he started teaching classes on Mary at Wheaton shortly after his arrival in 2011, Milliner was surprised to see such consistent interest in the course from the largely Protestant student body.

“Protestant interest in Mary is increasing steadily,” he said.

“But thankfully it has been growing in Catholic circles as well.” It is easy to forget, Milliner said, that in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, attention to Mary declined dramatically even in Catholic circles, a topic explored in Charlene Spretnak’s 2004 book “Missing Mary.”

The culture may soon move on from Mary, but Milliner believes Christians should keep her close, without fearing that love for the mother of God could threaten their love of Jesus.

“Love for Mary is a natural outgrowth of love for Christ,” he said.

“They are not in competition, any more than love for my in-laws is in competition with love for my wife,” he said. “In short, meet the parents!”

- Whitney Bauck is an author at RNS.

- First published in RNS. Republished with permission.

News category: Analysis and Comment.