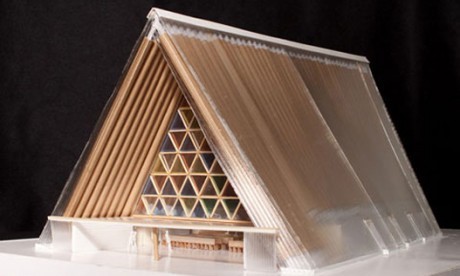

Christchurch’s interim cardboard cathedral should be good to go by December. Of course it’s not all cardboard and may well last over 50 years but that’s not the point. It’s the sense of impermanence that has promise.

Cathedrals tend to play down impermanence, opting instead for solid and imposing, but they’ve always had a more ethereal and symbolic function. In medieval times they represented paradise. Even their huge wooden doors formed part of the illusion, drawing worshippers into heavenly realms. To step across the threshold was to enter the dwelling place of God, an idea connected back to the Jewish story of the Ten Commandments.

God gives Moses the commandments etched on two stone tablets. They travel in a box known as the Ark of the Covenant, becoming a powerful symbol of God’s presence. Once the people settled and built the Jerusalem temple the ark rested in the holy of holies, a place only accessible once a year by the high priest.

Change being the only certainty, world politics intervened in 586 BCE . King Nebuchadnezzar invaded, destroyed the temple and the ark disappeared. When the temple was rebuilt, all that was left in the holy of holies was space. The symbol of God’s presence had become a great emptiness. A bit like the ruin that Christchurch Cathedral is now.

The shattering of a religious symbol disturbs more than the physical ground on which we stand. Perhaps because they hover in an inexplicable way on the fault lines of the soul, the places where what matters is most fragile.

Whilst an architect may be the actual designer of a cathedral, they are formed out of much more than one person’s creative imaginings. There’s the long religious tradition that stretches back beyond Christianity and the diverse spiritual mix of the surrounding community complete with their troubles, joys, hopes and dreams. It’s complicated.

All of this comes together in a building with a religious purpose that unexpectedly means more than people anticipate, whatever their beliefs or lack of them. It’s hard to explain or even talk about as one woman discovered when she called Christchurch Cathedral ‘a dear, dear, wee thing’. An awkward phrase but she’s expressing an intimate and deeply felt connection to the whole package, seen and unseen.

At their best, within the security of its walls and its religious rituals, cathedrals offer space; to be vulnerable, to not know in a world that values certainty, to entertain more questions than answers and to hold all-comers in the fragility and impermanence of that unknowing.

These strange, towering edifices, whether cardboard or concrete, hold a much more significant place in people’s hearts than we often realise. With their processions, costumes, music, art and drama there’s a sense that even if you’ve given up God, someone is minding the space, the great emptiness of God’s presence. May it continue to be so for Christchurch.

Sources

- Sande Ramage in Vaughan Park

- Image: inhabit

News category: Analysis and Comment.