There is a rot at the core of schooling in New Zealand. The Ministry of Education follows unscientific advice and is in thrall to a flawed philosophy.

Education is awash with debates and dichotomies. Should schooling be about knowledge or personal discovery?

Should teachers provide motivation for learning or nurture it intrinsically?

Should schools provide freedom now or preparation for freedom as an adult?

For most teachers and parents, answers lie somewhere in the middle.

As Education Minister Chris Hipkins said: Education is a broad church. It’s a wide spectrum with traditionalists at the one end and progressives at the other, all of whom believe their formula works best. The key to the changes we’re making is to work hard to capture the best of each world view and bring the whole spectrum along.

Few could disagree.

Progress calls for solutions, not endless battles between extremes.

However, Hipkins’ statement overlooks that official policy and ‘research’ in New Zealand is far from ordinary.

Over the past few decades, the national curriculum and assessment have turned the school system into an experiment in child-centred orthodoxy.

The philosophy has changed everything from what is taught to the teacher’s role in the classroom. It has transformed the purpose of school.

By appealing to the inarguable idea that children should be at the centre of decisions about their learning, children-centred orthodoxy has undermined subject knowledge.

It has told teachers they are at their most professional when they let their students lead.

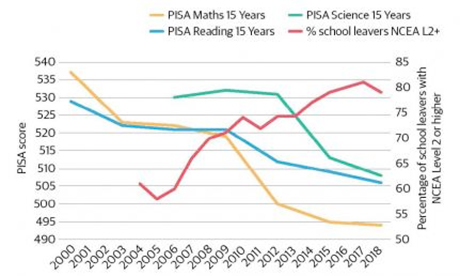

Consequently, educational standards have plummeted. Despite a 32% real rise in per-pupil spending since 2001, students have gone from world-leading to decidedly average.

In reading, maths and science students now perform far worse than the previous generation just eighteen years ago. In all three subjects, 15-year-olds have lost the equivalent of between three and six terms’ worth of schooling. Far fewer pupils today perform at the highest levels. Far more lack the most basic proficiency.

Worse, in the latest round of OECD testing, New Zealand recorded the strongest relationship between socioeconomic background and educational performance of all its comparator English-speaking countries.

Yet, without these international metrics, there would be no way to see this systemic failure. In fact, so strong is the grip of child-centred orthodoxy that the data from the national assessment, NCEA, shows the opposite. Continue reading

Additional readingNews category: Analysis and Comment.